The Enlightenment Didn’t Cause the Haitian Revolution

Enslaved Africans in Saint-Domingue had many reasons to revolt... the Enlightenment wasn't one of them

Table of Contents

My Medium Friends can read this essay on Medium.

Love the community on Substack? Read this essay there.

Hundreds of thousands of teenagers worldwide take the AP World History test every May. Students can demonstrate what they’ve learned about important moments in world history. The American (North American), French, Haitian, and Latin American Revolutions, which textbooks call the Atlantic Revolutions, are one of those topics. This roughly fifty-year period appears not only in the AP World History framework but also in many state curricula. For most American students, learning about the Atlantic Revolutions is often the only time they learn anything about Haiti.

Many Americans are unfamiliar with Haiti’s history. When Haiti shows up in the media, it’s because of a political crisis or a natural disaster. It’s actually a good thing they learn about the Haitian Revolution as part of the Atlantic Revolutions. The Haitian Revolution was easily the most radical of the Atlantic Revolutions. It was the only successful revolution by enslaved Africans that led to the permanent abolition of slavery. Despite its significance, I regularly taught many high school students who were surprised by and had never heard of the Haitian Revolution.

The drawback to teaching the Haitian Revolution within the context of the Atlantic Revolutions is that it frequently leads to many students and teachers misunderstanding the causes of the Haitian Revolution. Students frequently claim that enslaved Africans revolted because they learned about European Enlightenment values. It’s a bit problematic to think that enslaved Africans in the French colony of Saint-Domingue revolted because the same Europeans who enslaved Africans also taught them the values of freedom and liberty that inspired a revolution.

It doesn’t help that many popular world history textbooks reinforce this idea. In Ways of the World, Robert Strayer and Eric Nelson claim:

The Atlantic basin had become a world of intellectual and cultural exchange… The ideas that animated the Atlantic revolutions derived from the European Enlightenment and were shared across the ocean in newspapers, books, and pamphlets. At the heart of these ideas was the radical notion that human political and social arrangements could be engineered, and improved, by human action.

European Enlightenment ideas did circulate in the Atlantic World, but so did African ideas. Europeans didn’t have a monopoly on the concept of liberty. The vast majority of enslaved Africans in Saint-Domingue were born in Africa and had been captured in wars between rival African states. The enslaved Africans didn’t need to read John Locke to learn about liberty; they had experienced the loss of it firsthand when they were enslaved in Africa and sold to European slavers along the coast.

Another problematic claim is that the enslaved Africans revolted in 1791 because they saw other people revolt. In Traditions and Encounters, the authors point to the American and French Revolutions as the reason enslaved Africans revolted:

The success of the American revolution appealed not only to French social reformers but also to enslaved people and free people of color in the Caribbean. But on the French portion of the island of Hispaniola it was the French revolution that provided the immediate inspiration and the opportunity for the revolution that broke out there in 1791.

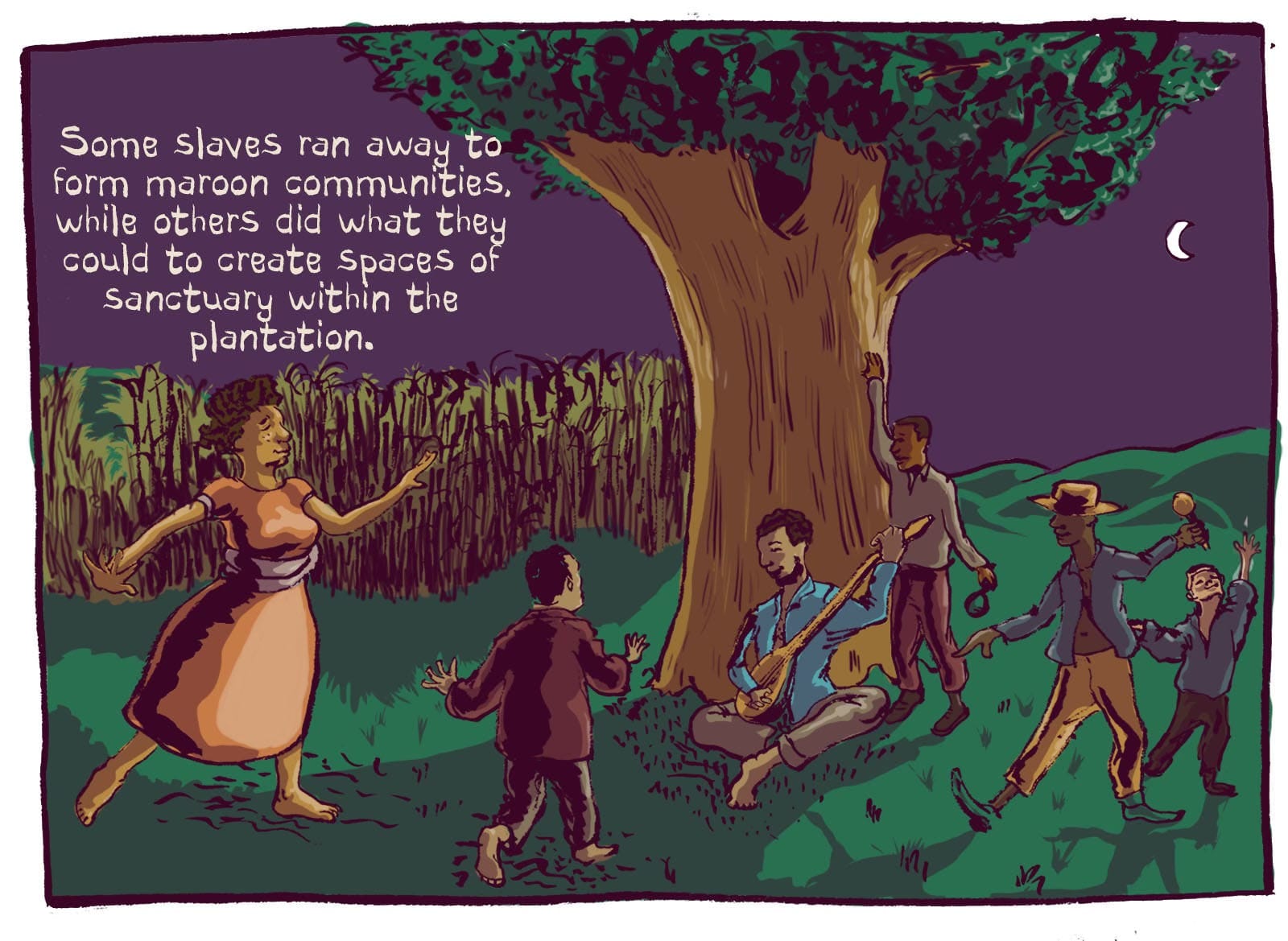

While Whites and free people of color on Saint-Domingue might have been inspired to push for more rights after seeing what happened in the United States and France, enslaved Africans on Saint-Domingue already knew how to revolt and fight back against their enslavement. For at least thirty years before the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution, enslaved Africans regularly resisted in various ways. In A Secret among the Blacks: Slave Resistance before the Haitian Revolution, John Garrigus describes how enslaved Africans practiced different forms of cultural resistance and engaged in work stoppages on plantations. Crystal Eddins has written about the long history of marronage among enslaved Africans on Saint-Domingue. They resisted by liberating themselves. They escaped from the brutality of the plantations and established their own communities across the island. Enslaved Africans didn’t need to see wealthy White American landowners or the French Third Estate revolt to become inspired to resist. By simply surviving, establishing maroon communities, and preserving their culture, enslaved Africans on Saint-Domingue had lived a life of resistance.

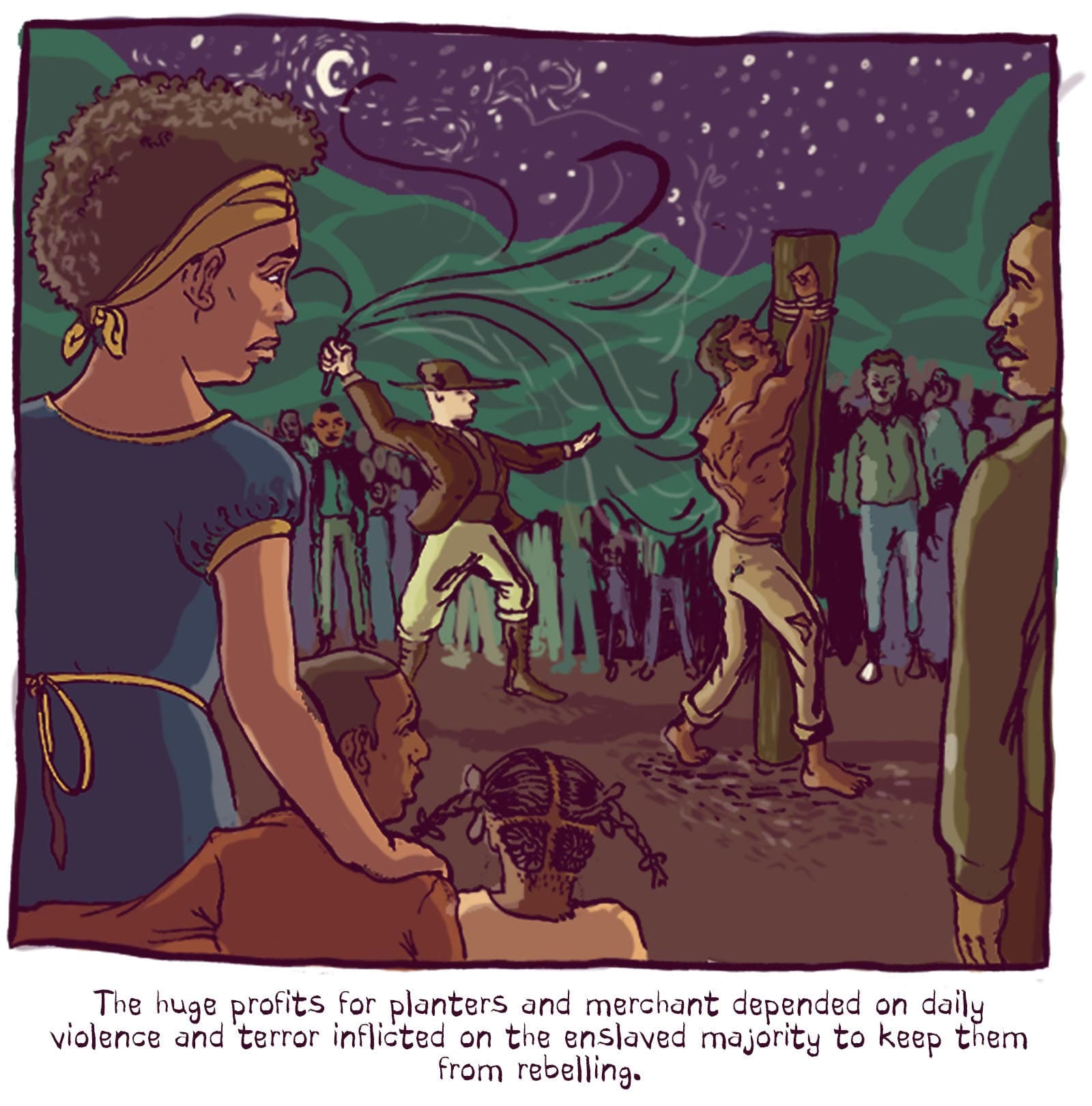

If the Enlightenment didn’t cause enslaved Africans to revolt, what did? It’s surprisingly simple, but the answer is probably not the one many people want to hear. Enslaved Africans revolted because European plantation slavery was more violent and brutal than we would like to admit. In just over a century, the French imported at least 800,000 enslaved Africans to Saint-Domingue; at the start of the Haitian Revolution, there were about 500,000 enslaved Africans. Some died natural deaths, but many were worked to death on plantations. Plantation managers regularly tortured enslaved Africans to keep them working.

In the early 1780s, Girod de Chantrans was a European living in Saint-Domingue. He described the willingness of plantation managers and owners to use violence:

Although nowadays Saint Domingue’s planters cannot fairly be accused of killing their slaves for pleasure, they do commonly commit acts of cruelty that do not kill, which they hope will reinforce discipline. Note also that most people in charge of properties are not their owners, and it matters little to them if a slave lives or dies, providing their salaries are paid…

Chantrans further described enslaved Africans working on a sugar plantation:

There were a hundred men and women of different ages. They were all digging ditches in a field of cane; most were naked or covered in rags. The sun beat down on their heads and sweat ran all over their bodies. Tired by the heat and the weight of their pickaxes, and by a heavy soil baked hard enough to break their tools, they made great efforts to overcome every obstacle. A gloomy silence reigned among them; pain was visible on every face, but the hour of rest never came. The manager watched the workgang without pity, and several slave drivers armed with long whips, mixed in among the workers, dealt out harsh blows from time to time even to those who were obliged by weariness to slow down—men and women, young and old, without distinction.

When we read about the violence on plantations in the Americas, it’s easy to understand what caused or inspired enslaved Africans to revolt. Enlightenment ideas didn’t cause enslaved Africans to revolt; they revolted because the system Europeans created was more horrific than we want to imagine.

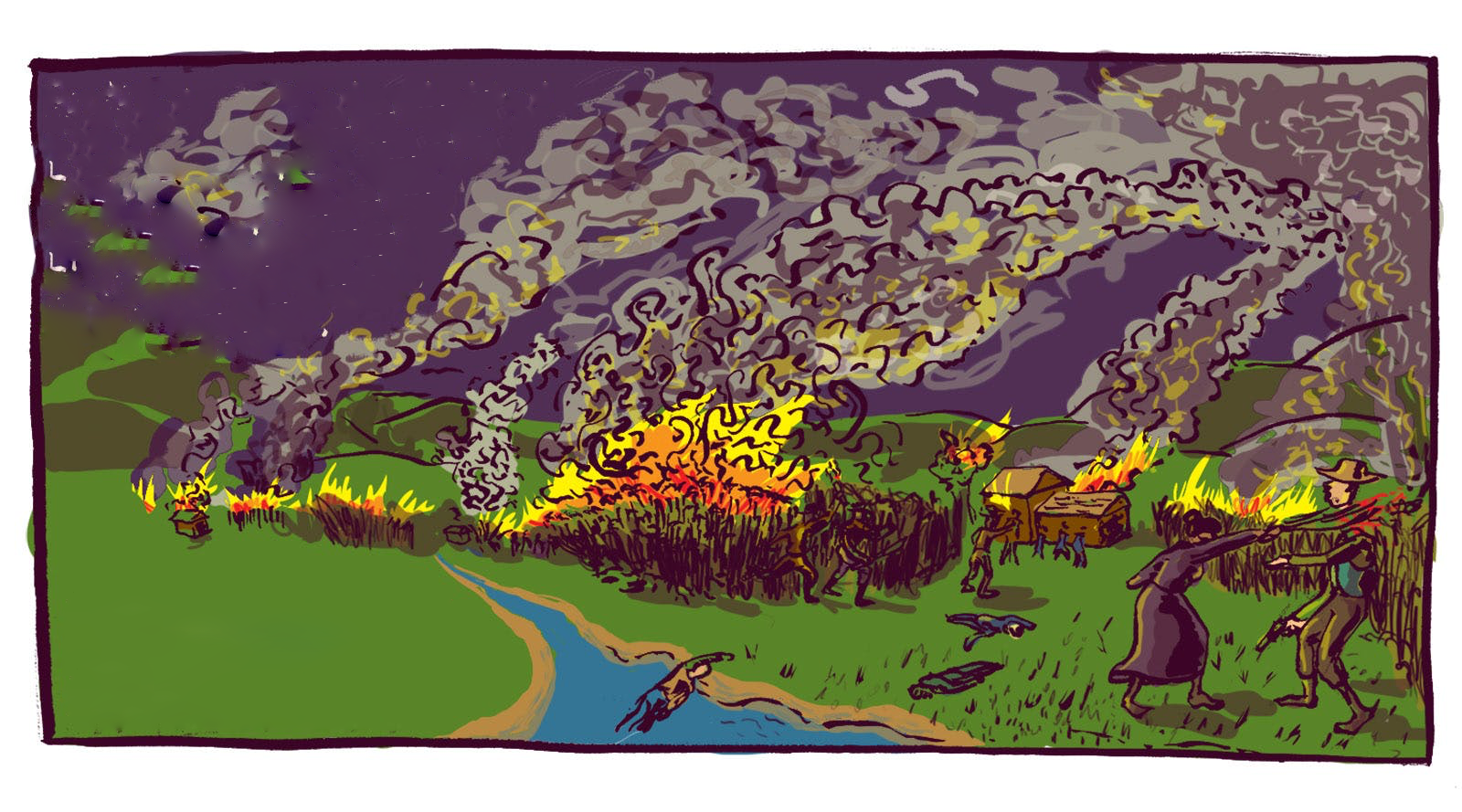

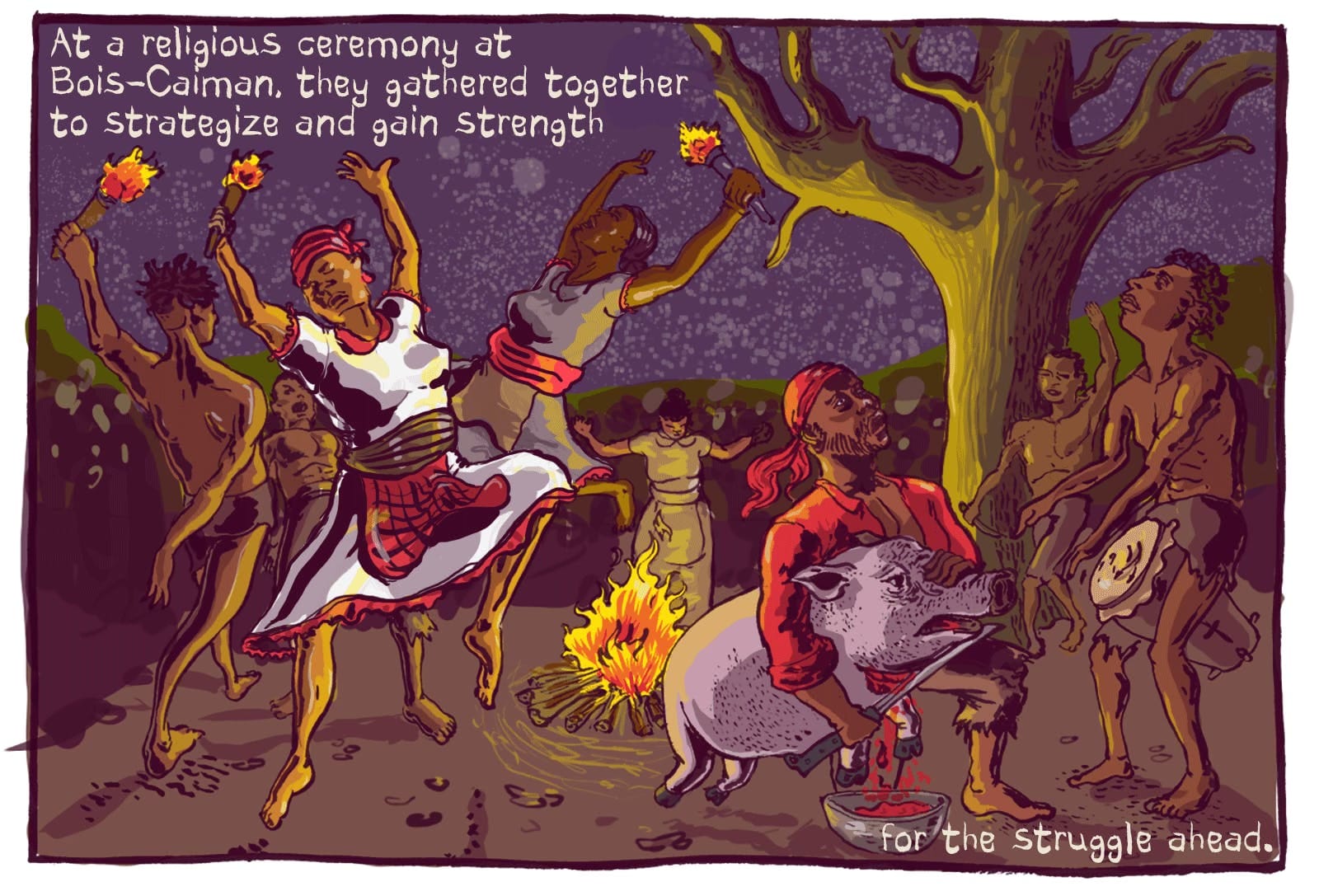

On the night of Sunday, August 21, Dutty Boukman and the other enslaved Africans who started the Haitian Revolution gathered at Bois-Caïman to participate in a West African ritual that involved the slaughter of a pig, whose blood the participants drank. This act bonded the community together as they prepared to launch their insurgency. The Haitian Revolution began the next night. The enslaved Africans who started the Haitian Revolution didn’t invoke John Locke, Thomas Jefferson, or the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. They drew on their shared African heritage.

During the next thirteen years, the Haitian Revolution took many turns. French forces killed Dutty Boukman less than three months after Bois-Caïman. Other revolutionaries, such as Toussaint Louverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines, emerged as leaders. These leaders, at times, invoked principles associated with the Enlightenment, but they were not the leaders who started the revolution. They also regularly justified their revolution by pointing to French violence. When we claim that the Enlightenment or White Europeans inspired or caused the Haitian Revolution, we obscure the main reasons enslaved Africans revolted and how they understood their actions. For the Haitian revolutionaries, the revolution was rooted in their own experiences and traditions.

All the illustrations come from Rocky Cotard and Laurent Dubois’ “The Slave Revolution That Gave Birth to Haiti,” a graphic history of the Haitian Revolution.

Liberating Narratives Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.