“The Enemies of Colonialism and Racism”: Intersectionality and Teaching Decolonization after 1965

Discussion of teaching decolonization intersectionally with a focus on Southern Africa

In 1999, I began teaching high school in Jackson Heights, New York. I taught a handful of students whose families had left Angola during the country’s civil war. I was vaguely aware of the conflict in Angola in the 1990s but didn’t fully understand it. I also thought it had been connected to South African apartheid, but I admit my understanding of Angola and Southern Africa was limited. As I got to know those Angolan students, I asked one to explain the conflict and why he and his Angolan classmates had left. He rolled his eyes and told me that no one understood it. He expressed how little other teachers understood his classmates’ situation and his own frustration with Angola. After a few minutes of talking, I understood the conflict began with Portuguese imperialism, but I was confused as he started to describe the different factions and participants in the war. Over the years, I often thought about those students and how I could better teach the conflict in Angola.

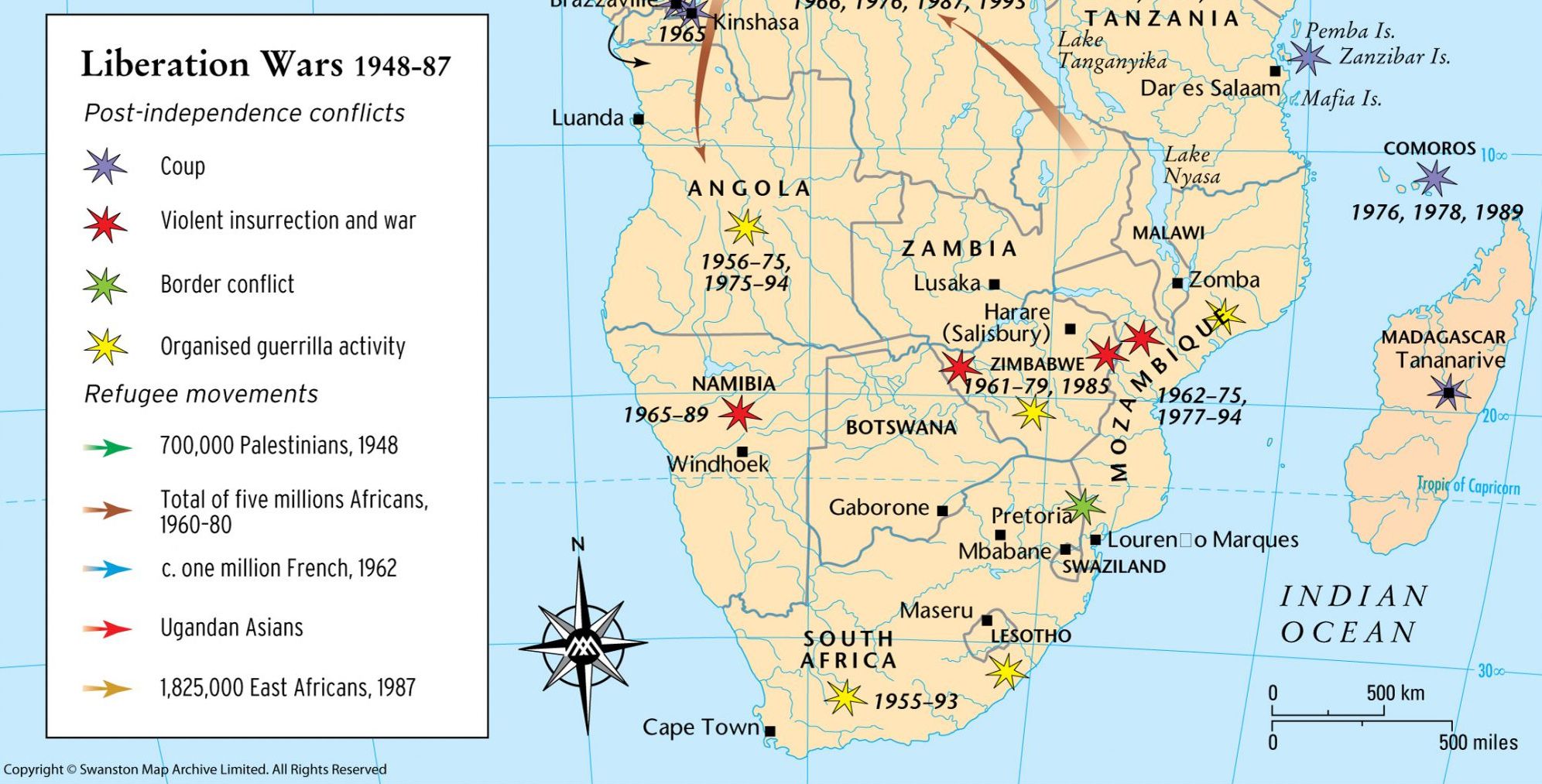

Left: Independence in Southern Africa. Source: Falola and Stapleton’s A History of Africa. Right: Political Conflicts in South Africa. Source: The Map Archive.

As I’ve written about teaching decolonization, I’ve noticed how the idea of decolonization evolved over the twentieth century. In 1919, anticolonial nationalists primarily focused on self-determination. There also was some overlap between opponents of empire and opponents of capitalism (i.e., communists). After the Second World War, decolonization and the Cold War were closely intertwined. Opponents of empire also increasingly focused on how they wanted to change cultural, economic, and social structures in newly independent countries. By 1960, many developing world feminists, opponents of apartheid, and African-American movements saw their own concerns as connected to the fight against empire.

At first, these connections can make teaching decolonization in Southern Africa seem too complicated for world history surveys. They only seem complicated when we overly focus on explaining every who, what, and when rather than on engaging with the broader issues. We can reframe how we teach decolonization from a simple focus on how formerly colonized nations gained political independence from Europe to exploring decolonization as an intersectional issue. By examining Southern Africa in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, we can help students see how decolonization was a critical global issue connected to other struggles in the late twentieth century.

Southern Africa and Decolonization

This content is for Paid Members

Unlock full access to Liberating Narratives and see the entire library of members-only content.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in