The Problem with Hyphenating Afroeurasia

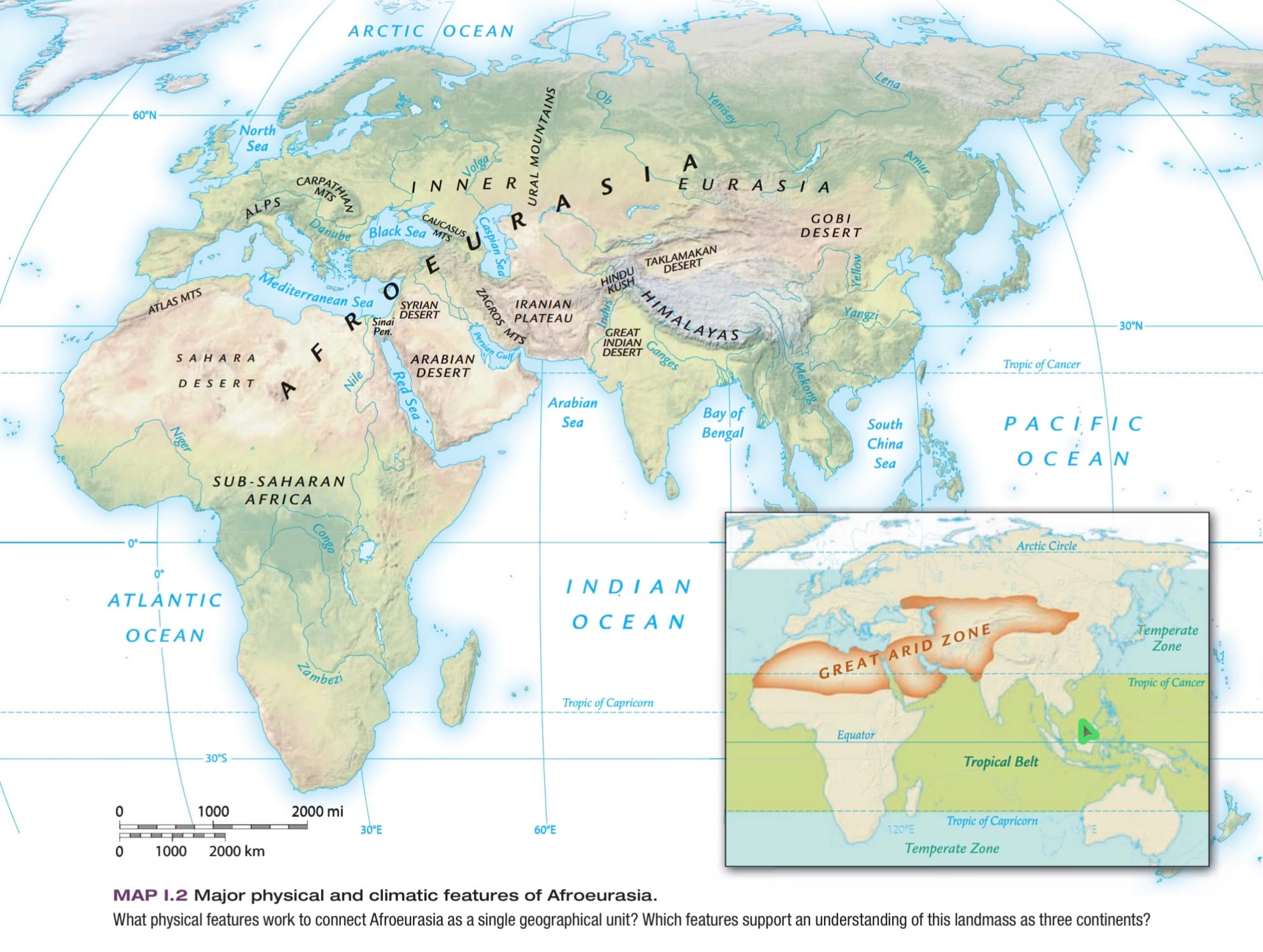

Hyphens suggest otherness; Afroeurasia has a long interconnected history

Table of Contents

📍 My Medium Friends can read this essay on Medium.

📍 Love the community on Substack? Read this essay there.

Hyphenating ethnicities has gone out of style, both figuratively and literally. All the major style guides recommend using “African Americans” or “Asian Americans” to describe groups of people. Hyphens suggest a sense of otherness. Removing hyphens encourages a sense of inclusion when talking about groups of people. Given this trend, it’s worth asking why so many world historians persist in writing “Afro-Eurasia”?

In the late twentieth century, many pioneers of modern world history advocated for seeing the historical integration of Africa, Asia, and Europe. They argued that instead of separating national or regional histories, we should focus on the long history of Africa, Asia, and Europe’s interconnectedness. Jerry Bentley and William McNeill promoted the idea of the “Old World.” Marshall Hodgson was one of the first to use “Afro-Eurasia.” Michael Pearson and Andre Gunter Frank suggested that “Afrasian” would be a better term, since it removes the hyphen. In the early 2000s, Ross Dunn oversaw the World History for Us All project, which used “Afroeurasia.”

Despite these earlier arguments about what to call the interconnected region of Africa, Asia, and Europe, Marshall Hodgson’s hyphenated “Afro-Eurasia” stuck. Open any world history textbook, except for Ross Dunn and Laura Mitchell’s Panorama: A World History, and you’ll find lots of hyphens. The CollegeBoard also uses the hyphenated form of “Afro-Eurasia” in its Course and Exam Description for Advanced Placement World History: Modern.

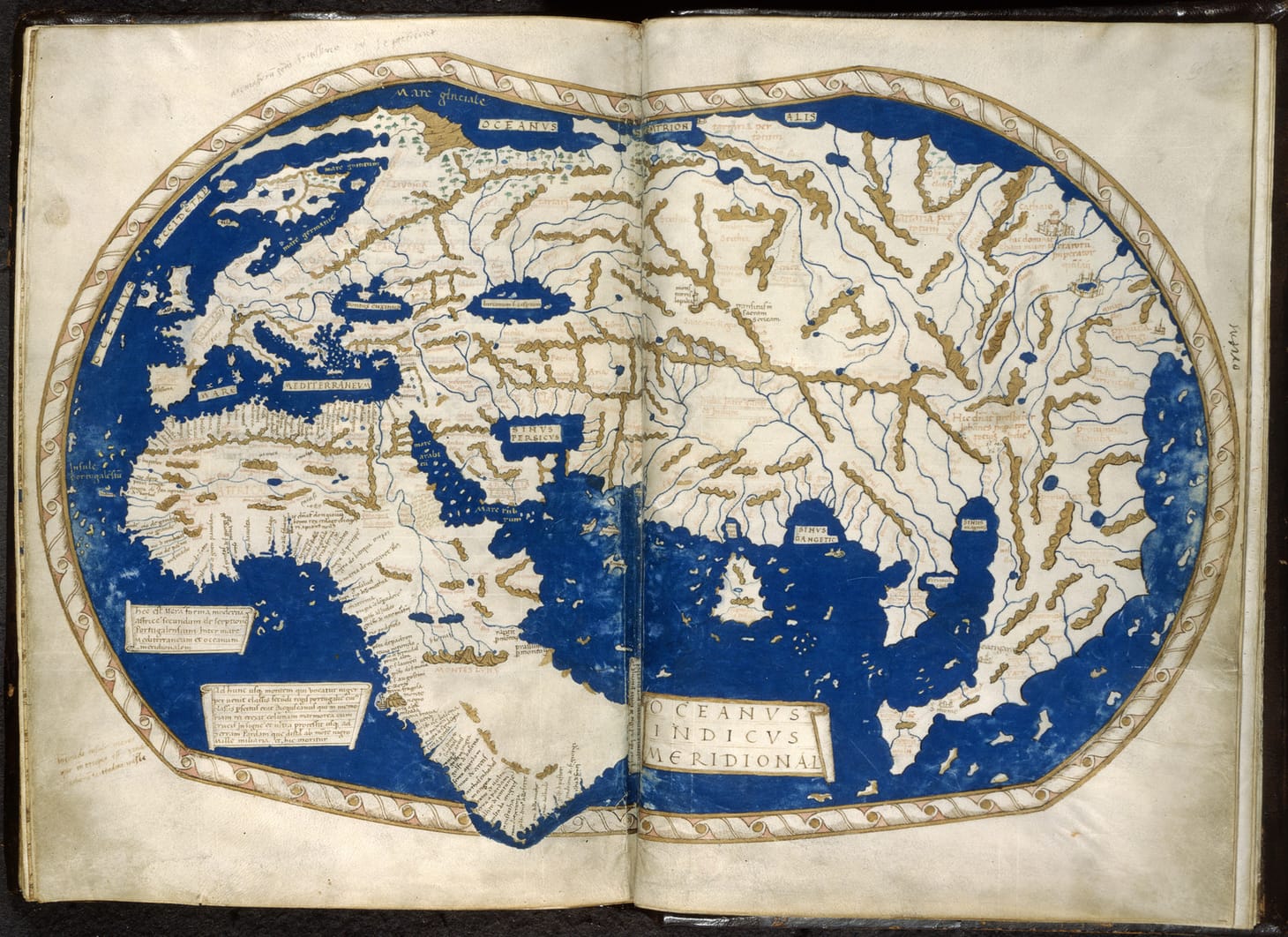

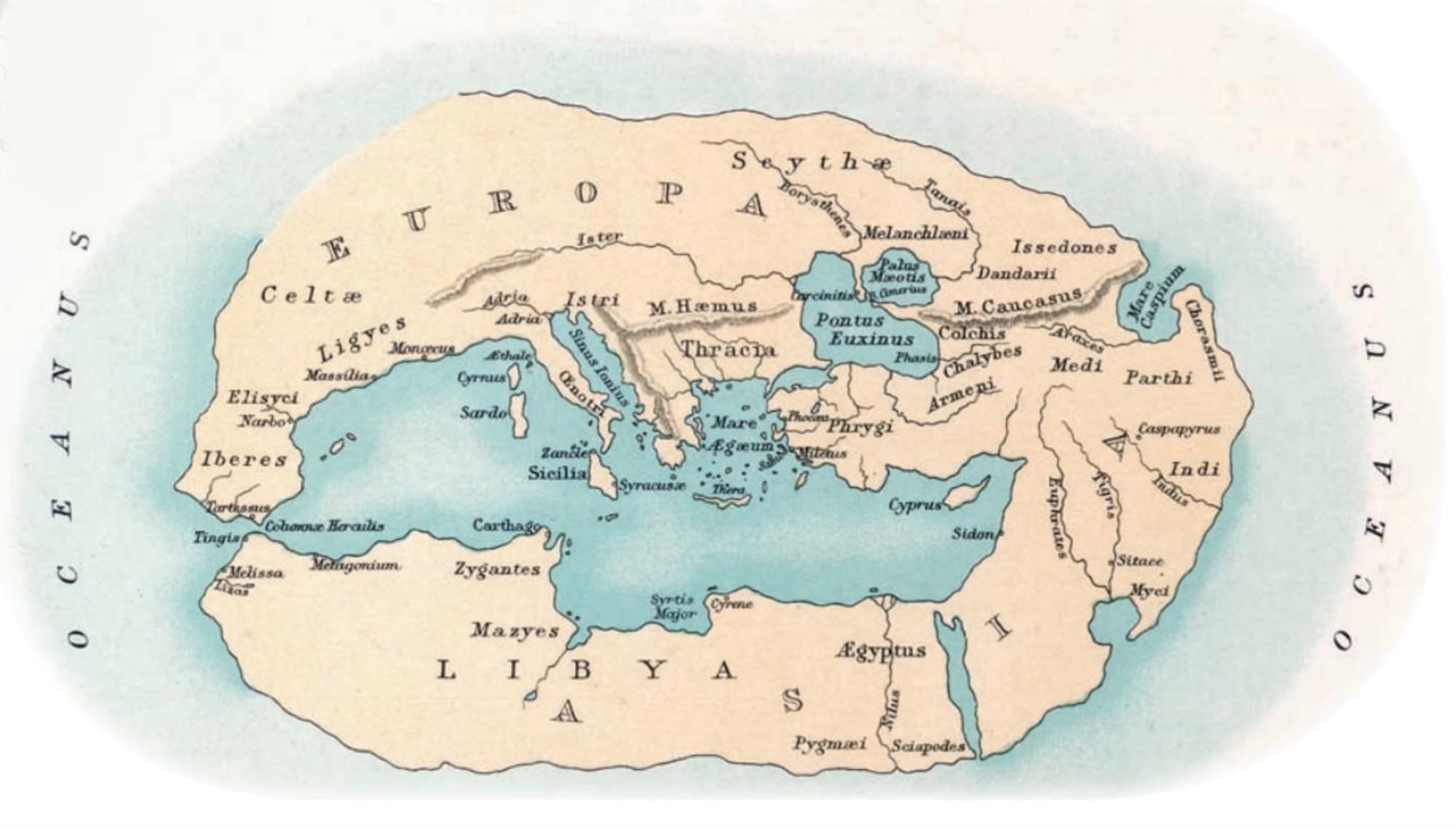

Left: Hecataeus of Miletus’ world map. Source: Maps Etc. Right: Ptolemy’s world map. Source: Vatican Library.

The idea of separating Africa from Eurasia doesn’t make sense when we survey thousands of years of how Afroeurasians understood their geography. Around 500 B.C.E., Hecataeus of Miletus, a Greek living under Persian rule, produced one of the oldest known maps of the world. Hecataeus depicted northern Africa as part of Asia. In the second century C.E., Ptolemy expanded Hecataeus’ map to include more of Africa, Asia, and Europe. Despite the differences in their maps, both geographers presented a single world in which Africa, Asia, and Europe were connected.

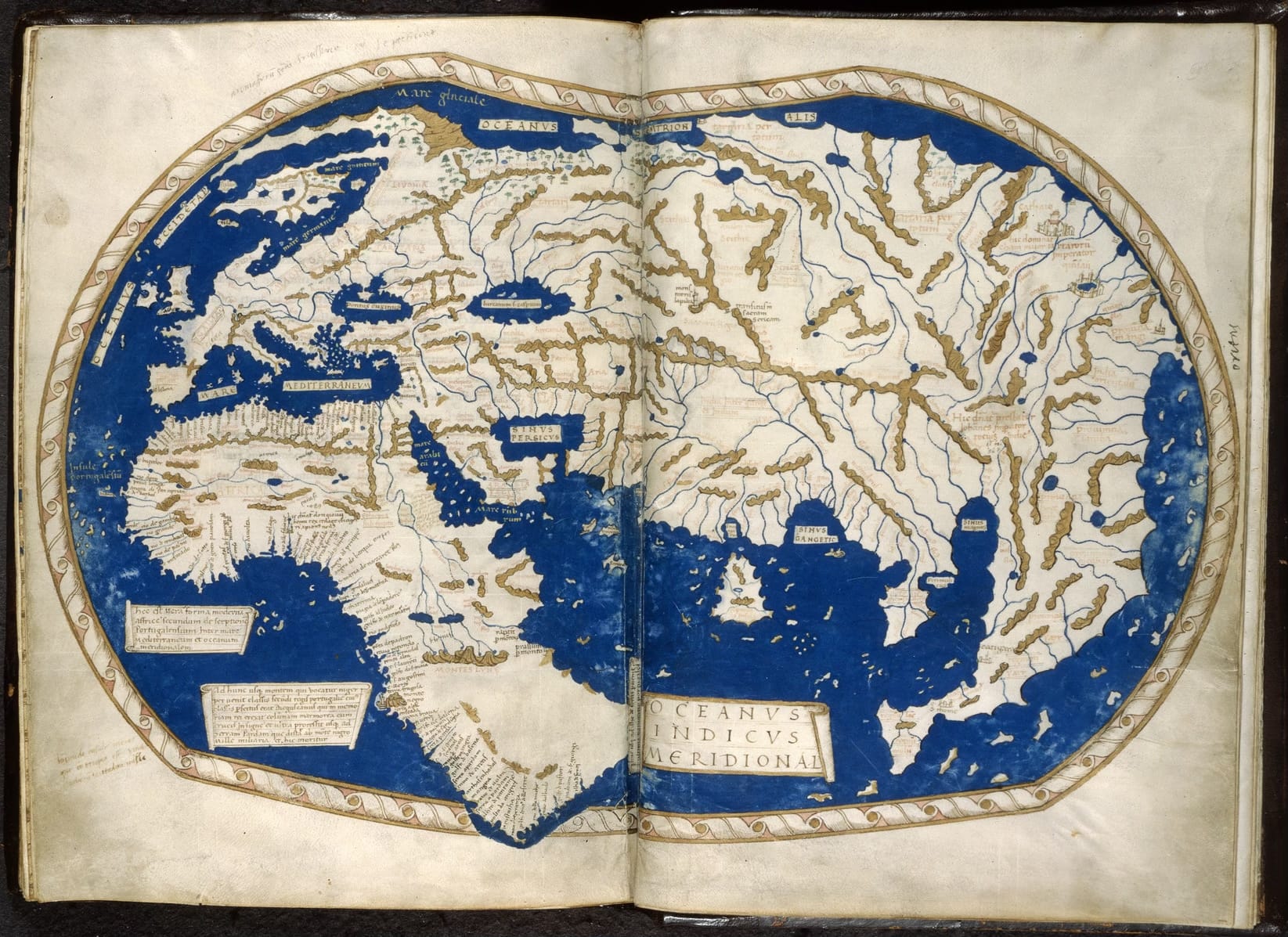

Left: Idrisi’s map of the world. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Right: Martellus’ map of the world. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The famous geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi, born in Ceuta in North Africa, produced a world map in the twelfth century at the court of Roger II of Sicily. While he adopted a style similar to Hecataeus, he “flipped” the map. Africa was on top! The German geographer Henricus Martellus Germanus made a world map in the fifteenth century, while he was in Florence. Europe was at the top, but the same basic design would have looked familiar.

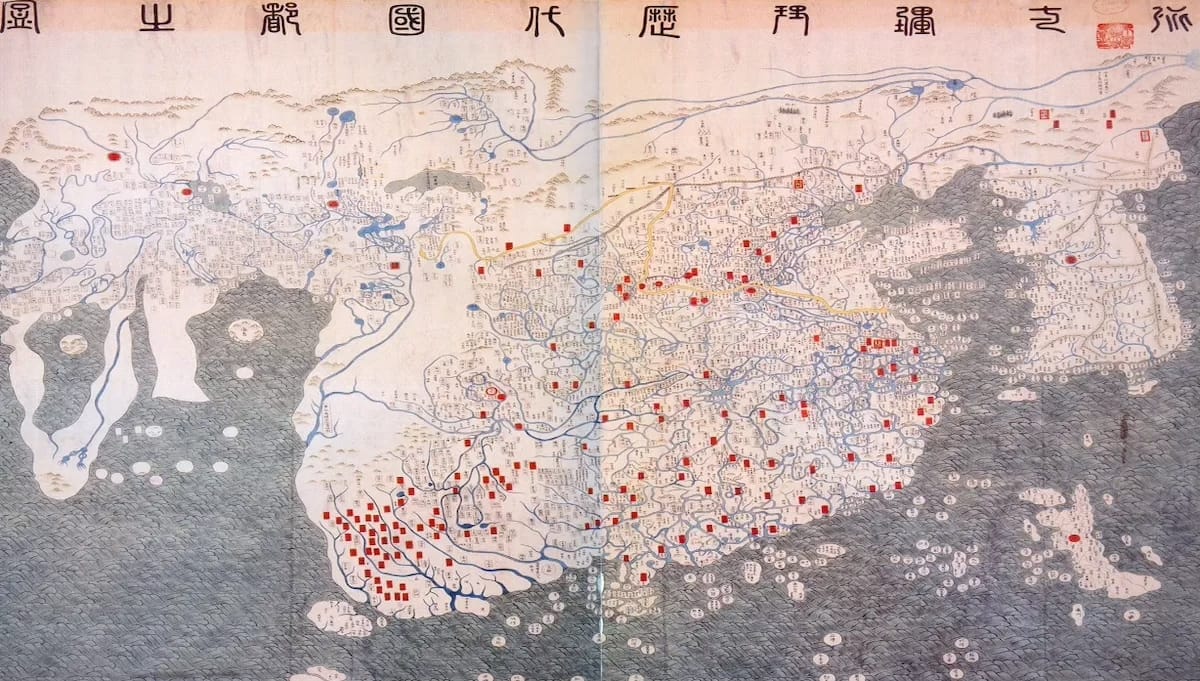

Left: Da Ming Hunyi Tu map. Source: Asia Times. Right: Gangnido Map. Source: Senses Atlas.

Even if we jump to the other side of Afroeurasia, we can find maps showing Afroeurasia as a single world. In the late fifteenth century, Ming Dynasty scholars produced the Da Ming Hunyi Tu map showing Afrouerasia from Japan to Africa as part of a large single landmass. In the early fifteenth century, Korean geographers Kwon Kun and Yi Hoe made the Gangnido map. They most likely copied the Chinese map. While they vastly underestimated the size of Africa, Afroeurasia was a large, connected landmass.

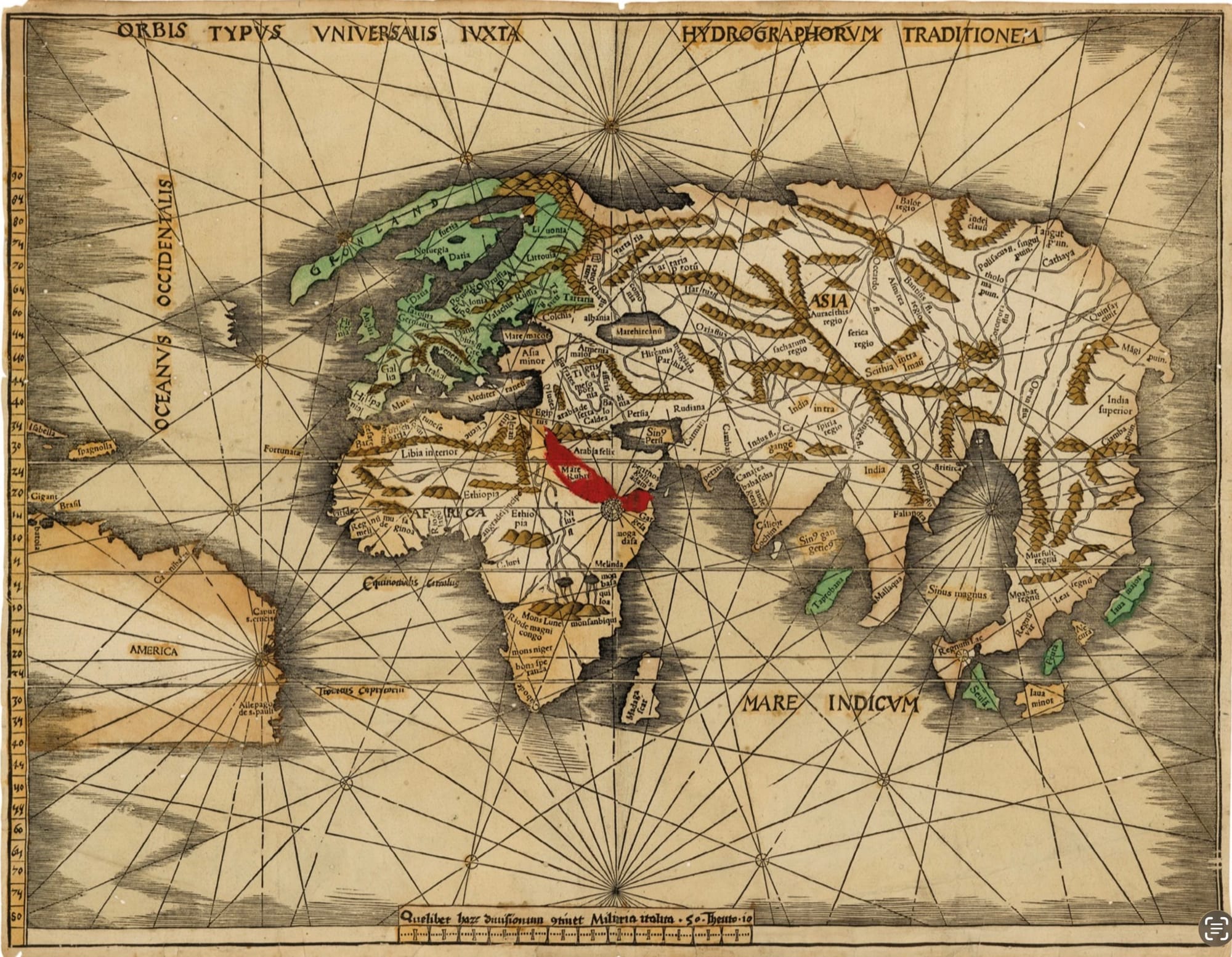

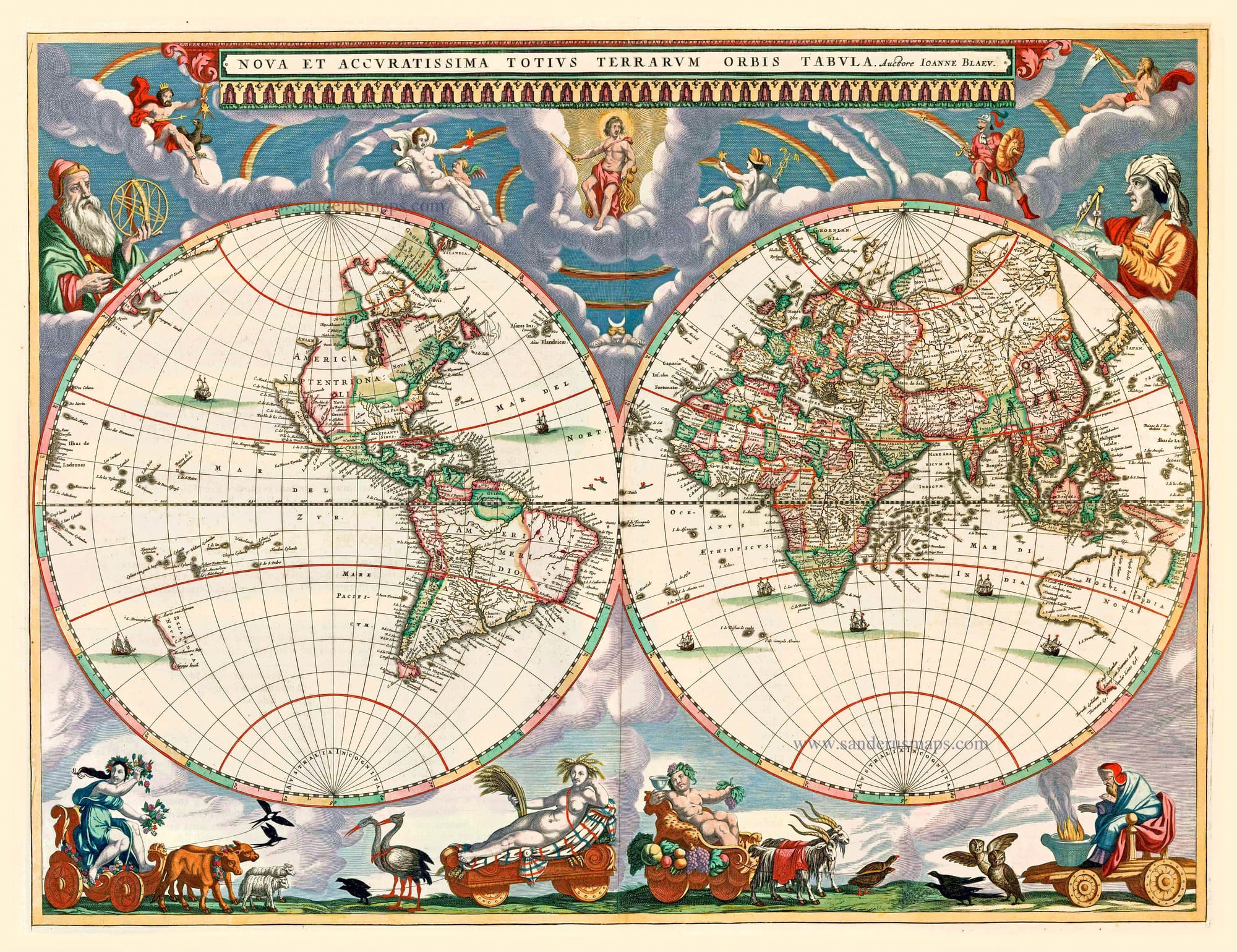

Left: Martin Waldseemuller Map from 1513. Source: Royal Museum Greenwich. Right: Joan Blaeu’s 1662 world map. Source: Sanderus.

If people across Afroeurasia imagined Africa, Asia, and Europe as part of a single landmass for 2,000 years, what prompted the hyphen? An obvious turning point might have been Columbus. In the 1500s, Europeans began colonizing and mapping the Americas, but that didn’t change how Europeans imagined Afroeurasia. Sixteenth and seventeenth-century maps continued to present a singular Afroeurasia.

To find the origin of the hyphen, we need to look to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the era of New Imperialism. During the 1800s, Europeans developed Social Darwinism to assert their “natural” racial superiority over others and justify conquering Africa, Asia, and the Pacific Islands. Europeans also employed cartography and geography in the service of imperialism. The rapid spread of European imperialism across Africa and Asia, in turn, shaped how Europeans mapped the world and understood themselves as a race.

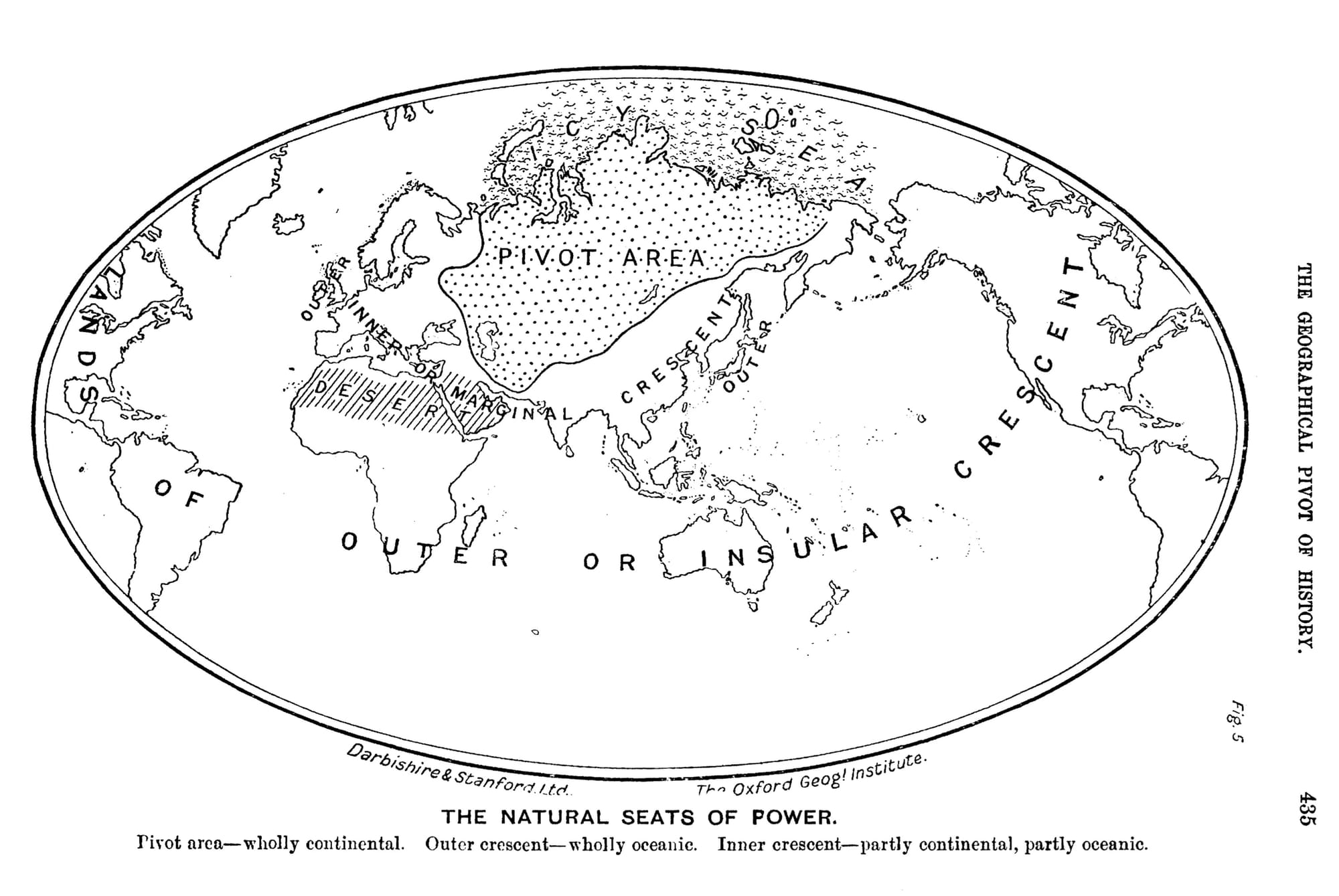

The idea of hyphenated Afro-Eurasia seems to originate with the British geographer Halford Mackinder at the London School of Economics and a Conservative member of Parliament. In 1904, he wrote “The Geographical Pivot of History.” He argued that Asia and Europe had long been connected as “Euro-Asia,” and that Asian “hordes” had repeatedly attempted to “invade” Europe. The final “invasion” was the Mongols in the 1200s. Mackinder argued that after the Mongols, European civilization developed. He even claimed that “European civilization is, in a very real sense, the outcome of the secular struggle against Asiatic invasion.” Mackinder clearly understood that Asia and Europe had a long history, which he couldn’t pretend didn’t influence Europe’s development. He hyphenated the two continents to emphasize their otherness while acknowledging their connection. Over time, Mackinder’s “Euro-Asia” became “Eurasia.”

But where does Africa fit in? In the same paper, Mackinder clearly expressed his thoughts about Africa:

The full meaning of Asiatic influence upon Europe is not, however, discernible until we come to the Mongol invasions of the fifteenth century; but before we analyze the essential facts concerning these, it is desirable to shift our geographical view-point from Europe, so that we may consider the Old World in its entirety. It is obvious that, since the rainfall is derived from the sea, the heart of the greatest land-mass is likely to be relatively dry. We are not, therefore, surprised to find that two-thirds of all the world's population is concentrated in relatively small areas along the margins of the great continent— in Europe, beside the Atlantic ocean; in the Indies and China, beside the Indian and Pacific oceans. A vast belt of almost uninhabited, because practically rainless, land extends as the Sahara completely across Northern Africa into Arabia. Central and Southern Africa were almost as completely severed from Europe and Asia throughout the greater part of history as were the Americas and Australia. In fact, the southern boundary of Europe was and is the Sahara rather than the Mediterranean, for it is the desert which divides the black man from the white. The continuous land-mass of Euro-Asia thus included between the ocean and the desert measures 21,000,000 square miles, or half of all the land on the globe, if we exclude from reckoning the deserts of Sahara and Arabia.

Mackinder acknowledged the existence of the “Old World,” but separated Africa from “Euro-Asia.” Mackinder’s Europe also included North Africa and stopped at the Sahara Desert, “which divides the black man from the white.” Africa was part of the “Old World,” but was also separate. Mackinder’s racism shaped his geographical understanding of Afroeurasia.

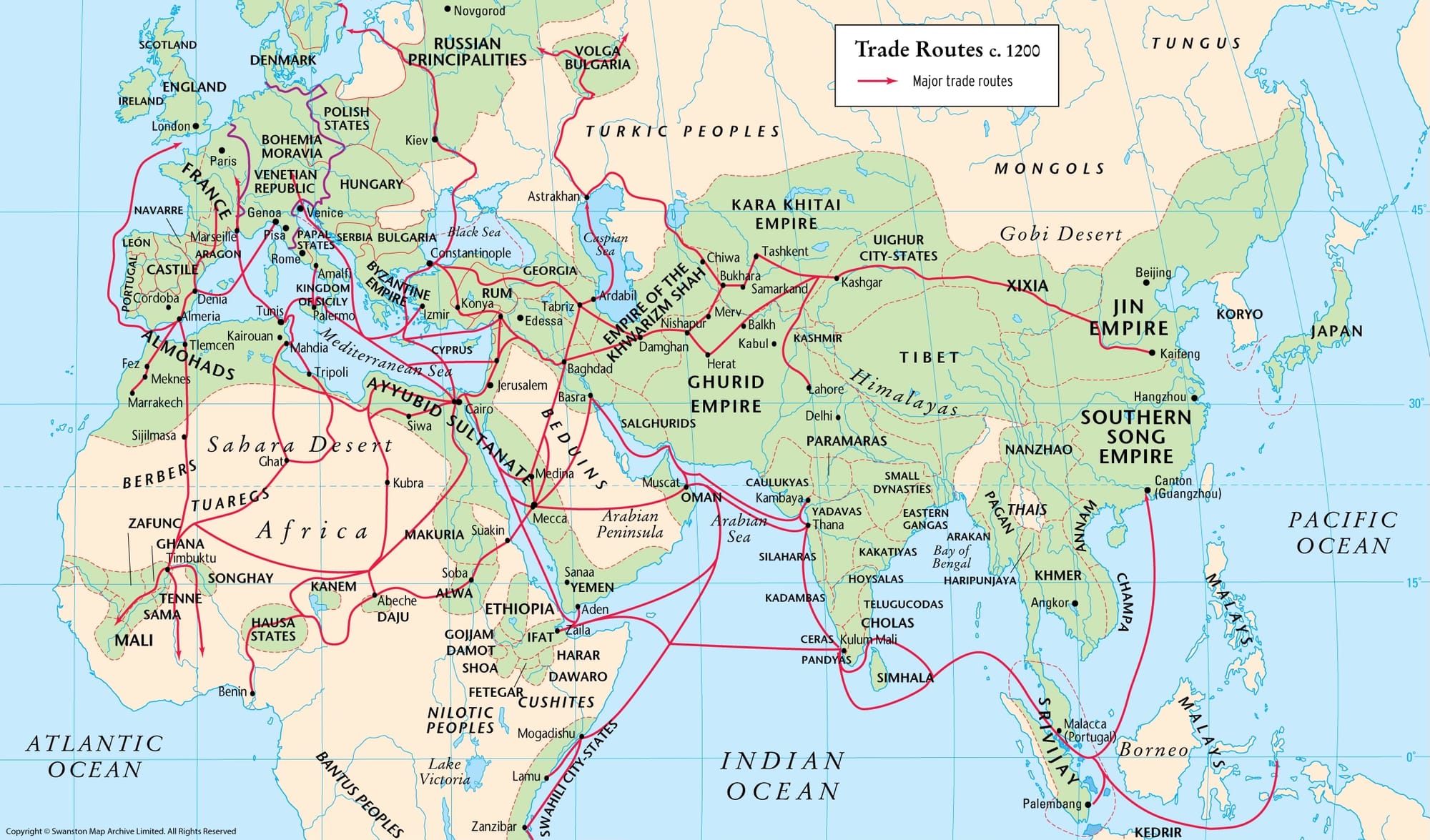

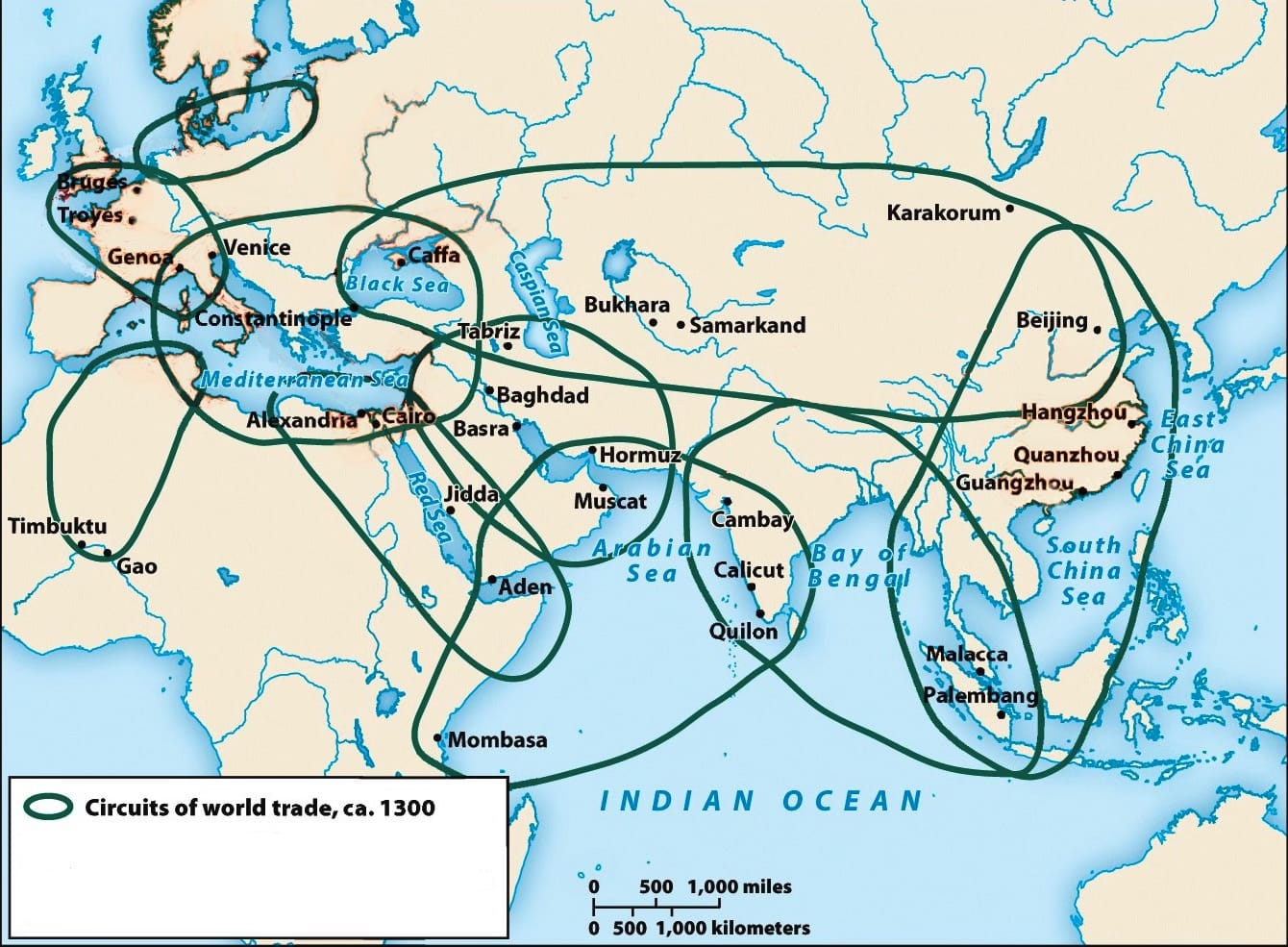

Left: Afroeurasian Trade, c.1200. Source: The Map Archive. Right: Afroeurasia’s major trade circuits, c.1300. Source: The Ways of the World.

When we use hyphenated Afro-Eurasia, we emphasize Africa’s otherness from an integrated Eurasia. As world historians, we know that’s historically inaccurate. Africa south of the Sahara played a critical role in Afroeurasian exchange for centuries. Trans-Saharan caravans and Indian Ocean ships closely connected West Africa and East Africa to the rest of Afroeurasia. We all know it’s problematic to hyphenate people. It’s now time to stop hyphenating “Afro-Eurasia” and start emphasizing the interconnectedness of Afroeurasia.

Liberating Narratives is written by Bram Hubbell. If you’ve valued reading this post, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your financial contribution supports independent, advertising-free materials for teachers. Thank you, friends.

Feel free to forward this message to a friend or colleague and let them know where they can subscribe. (Hint: it's here.)

If you have any comments or suggestions, please share them with me or post them below. I can also be reached on Bluesky, Threads, Facebook, Instagram, Mastodon, and email.

Liberating Narratives Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.