“A Generous Gift from Timur and Akbar”: Snapshots from the Mughal Empire

A discussion of how we can teach the Mughal Empire in world history courses with a focus on how the empire was multiethnic and diverse.

Over twenty years ago, I took my first trip to India. Given the challenges I faced on that first trip, I didn’t expect to fall in love with India. I have now been to India almost twenty times, and I’ve traveled all over the country. I even took fifteen high school students to India in 2019 for a two-week study tour. When one travels in India, it’s impossible not to notice how polarizing the legacy of the Mughal Empire is. For some Indians, the Mughals were a powerful cosmopolitan empire that oversaw one of the world’s wealthiest economies and built monuments such as the Taj Mahal. For other Indians, the Mughals were the epitome of evil—a Muslim empire that imposed Islam on India and persecuted Hindus.

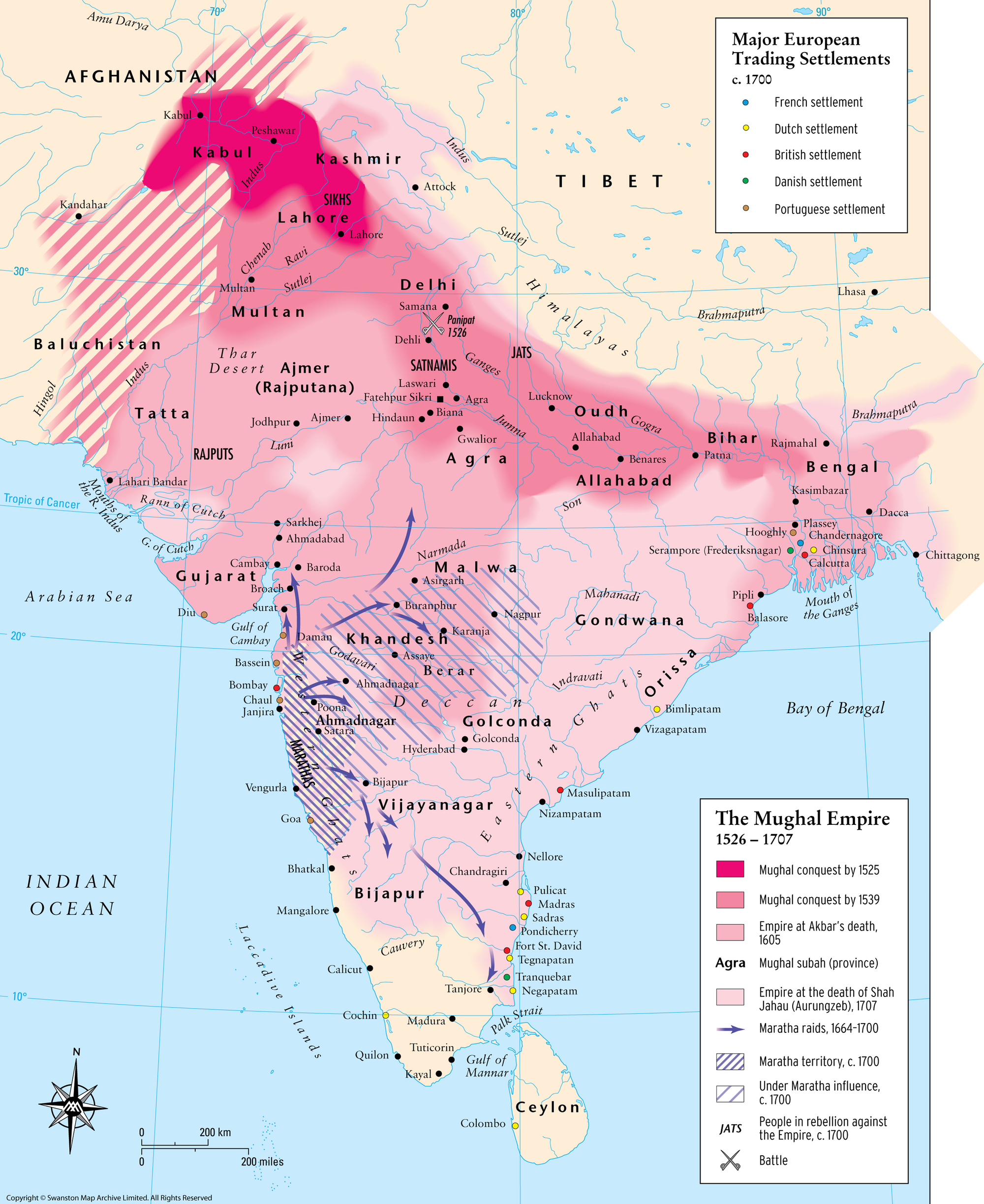

In many ways, the polarizing interpretations of the Mughals have also affected how many world history textbooks cover the Mughal Empire. Many textbooks present the Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals in a single chapter, so students think of the Mughal Empire as an Islamic empire first. The history of the Mughal Empire is then often presented in the familiar but problematic framing of rise and decline. There is Akbar, the cosmopolitan and tolerant emperor, who expanded the Mughal Empire, and there is Aurangzeb, the Muslim zealot, who brought about the empire’s decline. This episode of Crash Course presents this dichotomy in a way that students can easily understand.

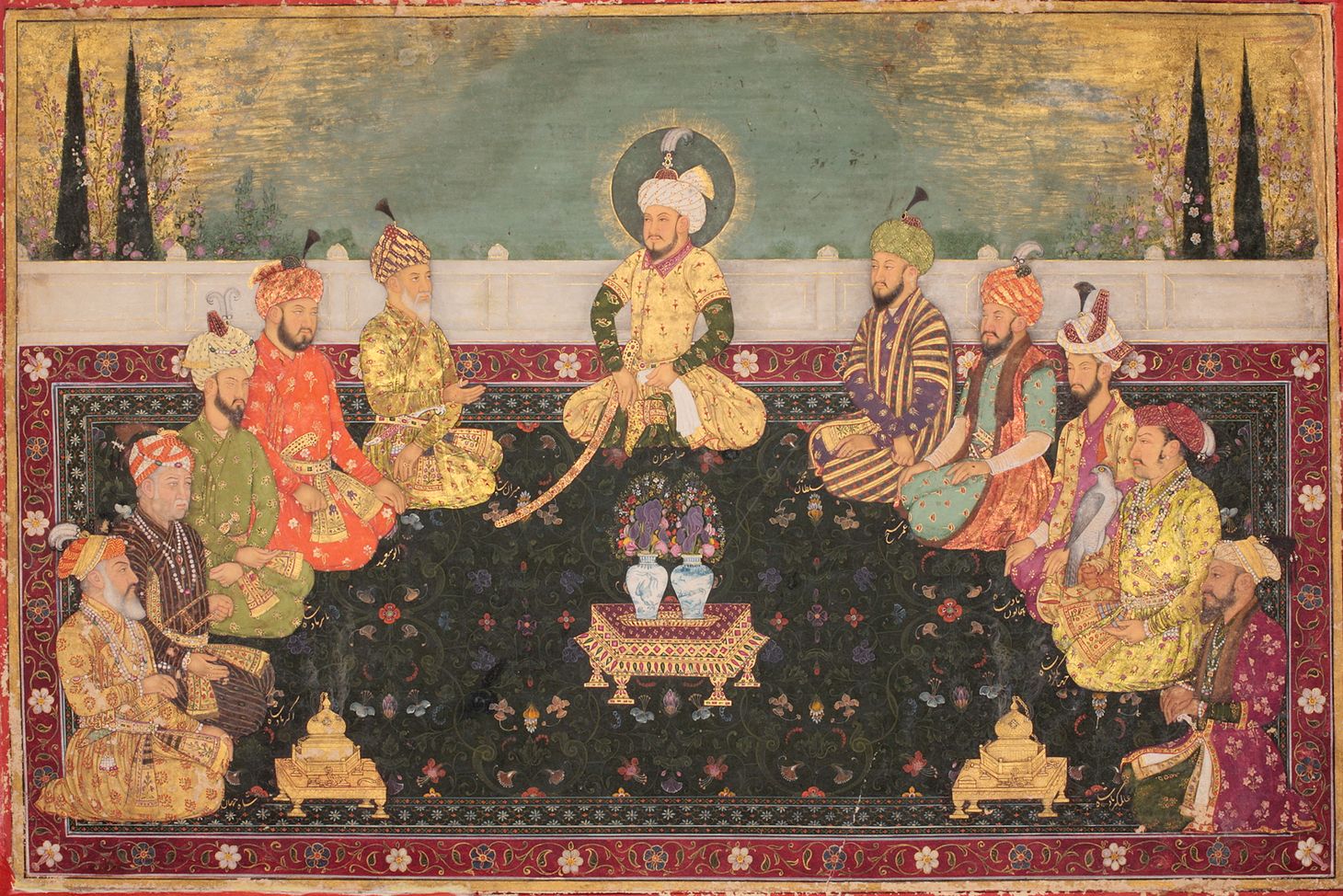

For many years, I kept refining and tweaking how I taught the Mughal Empire, so students could better understand the empire. The challenge is that the Mughal Empire was never one thing; it changed over 200 years. The organization of the Mughal state evolved. Mughal approaches to religion changed. Like so many other topics in world history, I realized that the most rewarding way to teach about the Mughals was to let the people who lived in the empire speak for themselves. Using a combination of textual and visual primary sources (paintings, artifacts, and architecture), students can begin to see the complexity of the Mughal Empire. They can see how it was a multiethnic and culturally diverse empire influenced by both Persian and Sanskrit cultural systems.

To help think about how we can teach the Mughal Empire, I will borrow the framework I used in October when I discussed the Ottoman Empire. By using a series of images combined with relevant textual sources, we can see the diversity and evolution of the Mughal Empire. One of the critical features of the Mughal Empire was how both Persian and Sanskrit cultures influenced the Mughals. In the paintings of the Mughal emperors, we can also see the importance of Timur to the Mughals. I recommend looking back at the first post about the Ottomans if you have questions about using historical images.