“Astonish the World”: Teaching Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Henry Christophe

Discussion of teaching Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Henry Christophe

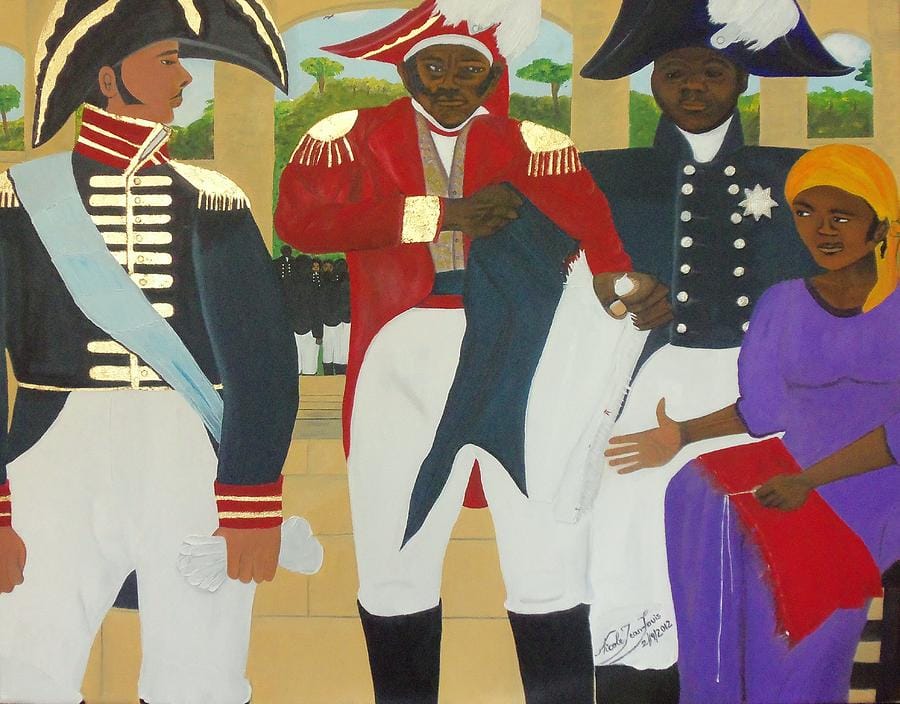

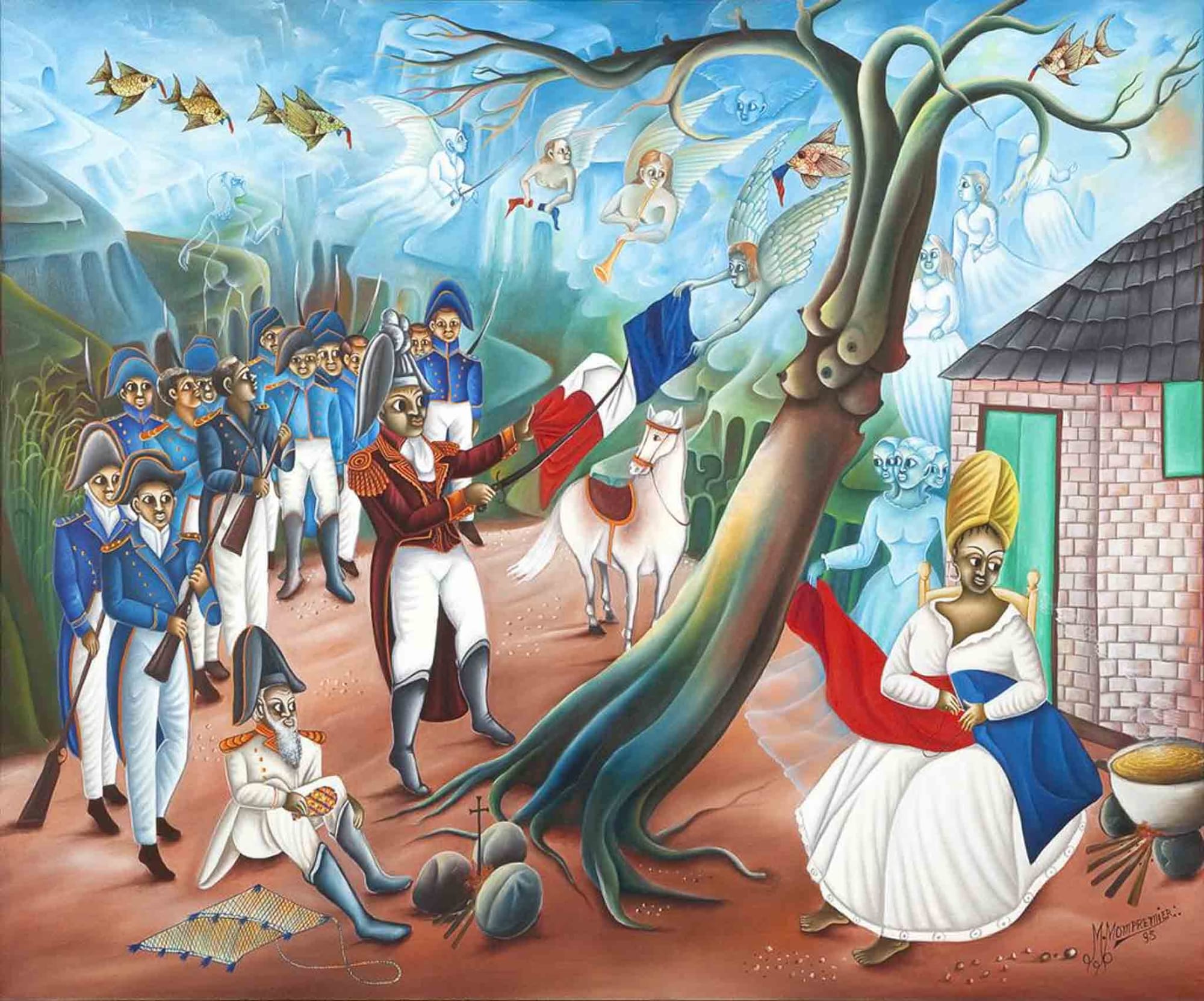

Many Haitian painters have painted the creation of the Haitian flag. The scene often depicts a group removing the white stripe from the French flag. The remaining blue and red strips became the basis for the Haitian flag. For his history of the Haitian Revolution, Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution, Laurent Dubois used Madsen Mompremier’s Dessalines Ripping the White from the Flag. The painting at the top of this post is Nicole Jean-Louis’ Making of the Haitian Flag.

If you ask students to guess who is ripping the white out of the flag, they would probably say Toussaint Louverture. As the painting’s title above makes clear, it was Jean-Jacques Dessalines. There’s a logical reason students would guess Louverture. The Haitian Revolution is often taught as part of the Atlantic Revolutions. Students learn many names, and teachers choose how many names to present to students. Louverture is usually the only individual from the Haitian Revolution that AP World History students might learn by name.

However, if we look at how Haitians remember the revolution, Jean-Jacques Dessalines is arguably more significant. He was the person who led the Haitians to victory against the French. He renamed Sainte-Domingue as Haiti. It’s worth asking how Haitians’ memory and understanding of their revolution should influence how we teach it.

I previously wrote about teaching the short-term effects of the Haitian Revolution. One of the challenges is that the aftermath of the revolution was politically messy. Although all the leaders of the state agreed on the abolition of slavery and preventing France from taking over again, they had competing economic and political visions. Teaching those competing visions got easier this year. Julia Gaffield published I Have Avenged America: Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Haiti’s Fight for Freedom in July. In January, Marlene Daut published The First and Last King of Haiti: The Rise and Fall of Henry Christophe. Both books are excellent, and they can help teachers better understand how these two individuals influenced the outcome of the Haitian Revolution. As world history teachers, we often want students to know the causes and effects of historical events. We need to become more familiar with Dessalines and Christophe to understand the effects of the Haitian Revolution fully.

Textured Narratives of the Haitian Revolution

Daut and Gaffield are not writing traditional biographies that focus only on the lives of their subjects. They begin by establishing context, which is so critical to good world history. Their early chapters help teachers better understand why the Haitian Revolution began and how it unfolded.

Both authors comprehensively describe what French Saint-Domingue was like, especially for enslaved Africans. In the case of both Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Henry Christophe, we don’t know conclusively all the details of their early lives. To provide a better understanding of their early life experiences, Daut and Gaffield regularly describe the experiences of enslaved Africans on Saint-Domingue. For example, when Gaffield discusses Dessalines’ childhood, she explains how infant mortality for the children of enslaved Africans was high, and when children began working on plantations. These details help us understand Dessalines’ relationship with Toya, the woman he would later call his “aunt.”

Daut similarly provides details about the nature of slave markets in Saint-Domingue and the different ways enslaved Africans liberated themselves from plantations before discussing Christophe’s arrival in the colony from Grenada. We don’t know his exact experiences, but Daut provides enough context to imagine what Christophe’s arrival might have been like. Daut explains “how some of the Grenadians sold in Saint-Domingue naturally rebelled, still dreaming of and striving for freedom.” By the time we finish the chapter, we can easily imagine how these experiences shaped the man Christophe became. We can understand why he participated in the Haitian Revolution and the anti-colonial and anti-slavery policies he pursued as king.

By weaving together rich context and the personal experiences of Christophe and Dessalines, I put down these books with a much better understanding of the Haitian Revolution. World history textbooks regularly skim over the details of the revolution, so these books are an excellent way to fill in some of the gaps in our understanding.

Teaching Jean-Jacques Dessalines

Left: Source: Wikimedia Commons. Right: Source: Wikimedia Commons.

This content is for Paid Members

Unlock full access to Liberating Narratives and see the entire library of members-only content.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in