“Foreign Ships from Every Place”: The Indian Ocean as a Network of Exchange, c.1000-c.1900

A discussion of teaching the Indian Ocean in world history with a focus on continuities.

A few months ago, I was having breakfast in Kuala Lumpur and enjoying one of my favorite meals: a mini tiffin. Mini tiffins include dosas and idlis - two dishes associated with South Indian cuisine. On this trip, it was the same breakfast I had already eaten many times in Singapore and Malaysia. I found myself thinking about many previous trips around the Indian Ocean and the places where I had eaten similar breakfasts. There were countless places across India, Sri Lanka, and Southeast Asia. And then I remembered some special mini tiffins in Mombasa, Kenya and Hong Kong.

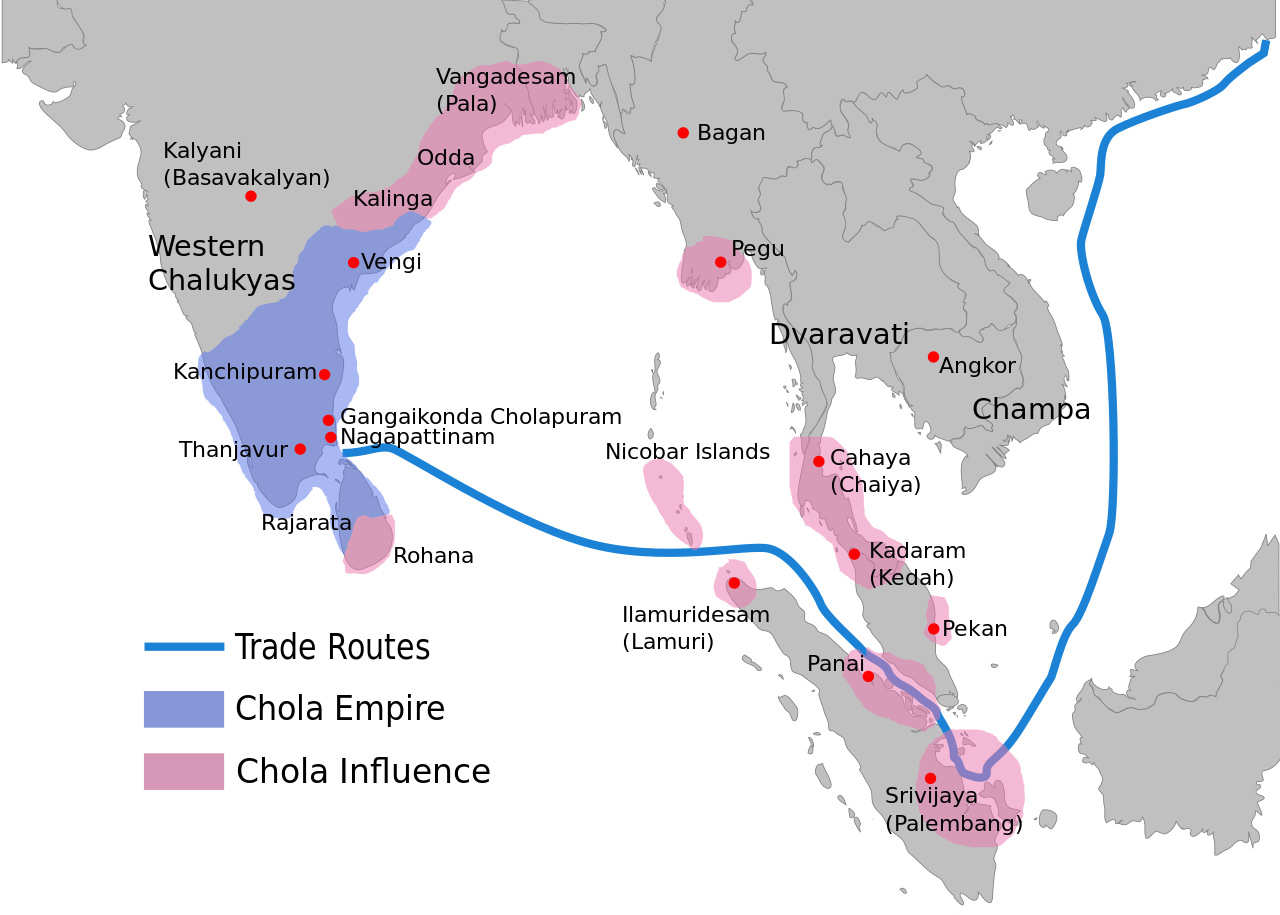

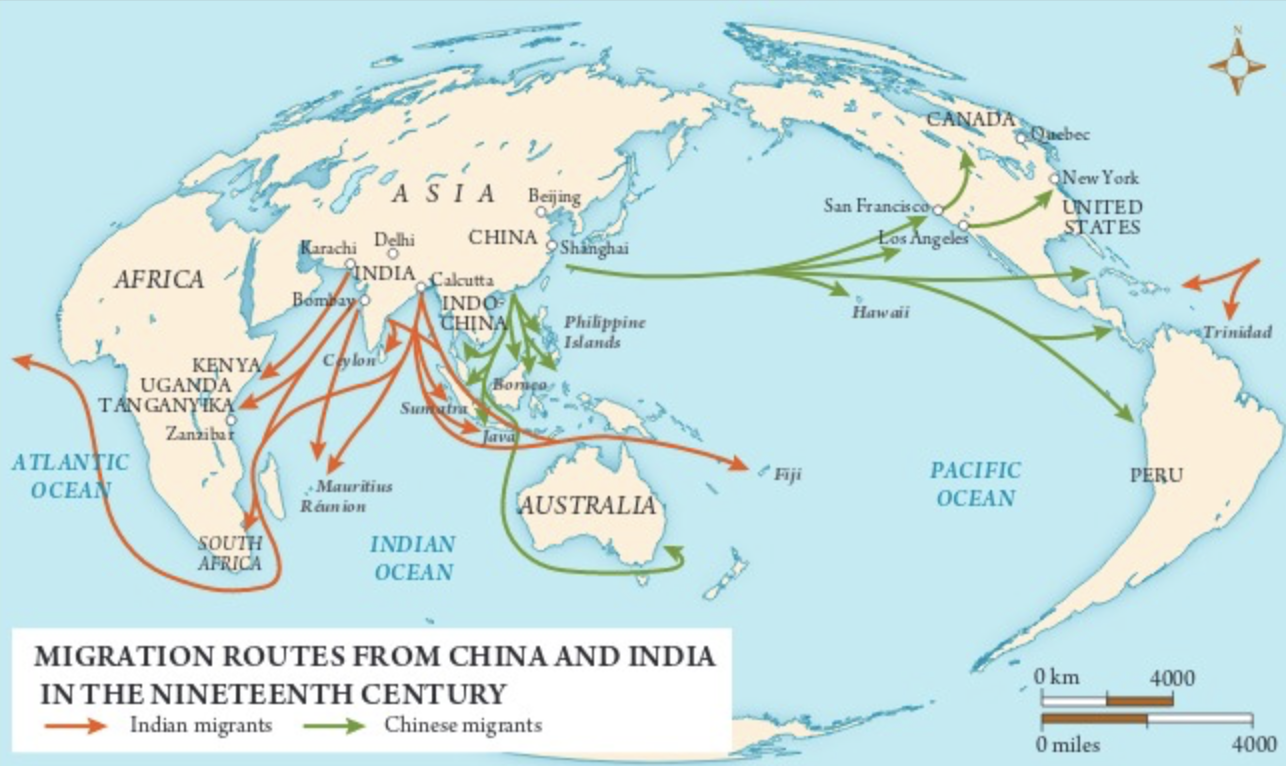

Foods can often be entry points for helping students learn history. The spread of South Indian food around the Indian Ocean can be traced back to the migration of Tamils in the nineteenth century. Tamils frequently migrated to work as plantation laborers across the British Empire. Over time, Tamil migrants established ethnic enclaves in many countries around the Indian Ocean and opened up restaurants serving South Indian food. But the Tamil migration of the nineteenth century had been preceded by earlier waves of migration from southern India to Southeast Asia. Such as the one during the Chola Empire. Historians refer to this earlier spread of Indian culture to Southeast Asia as Indianization.

Reflecting on these two distinct waves of migration of Tamils, I realized world history courses tend to present the earlier history of the Indian Ocean as separate from the later history of the Indian Ocean. There is the earlier pre-1500 Indian Ocean network of exchange and the later European-influenced Indian Ocean network of exchange. While it’s important to highlight changes in world history, such as the arrival of Europeans in the Indian Ocean, how do we help students see the continuities?

During the next month, I will discuss how we can teach the history of the Indian Ocean from c.1000 to c.1900 with an emphasis on continuities. This means focusing less on how Europeans influenced the patterns of exchanges and focusing more on the continuous spread of Arab, Chinese, Indian, and Persian influences. I also plan to highlight indigenous voices as much as possible. This means focusing less on the sources written by people who came into the Indian Ocean and focusing more on sources written by the people who have historically lived around the Indian Ocean.

Defining the Indian Ocean as a Network of Exchange

The current AP World History Course and Exam Description includes an entire unit focused on networks of exchange, but the phrase itself is never defined. While most teachers understand this phrase, our students might struggle to provide a clear definition. They might say a network of exchange is a trade network, but that only covers some aspects of a network of exchange.