“Listen to the Women For a Change”: The First International Women’s Conference and Late Twentieth-Century Global Feminism

Discussion of teaching late-twentieth-century global feminism

Most history teachers find teaching late twentieth and early twenty-first century history more challenging than earlier periods. As we approach the present and the experiences of our own lives, it can be difficult to decide which events were more historically significant and what narratives to present. As I’ve been writing about global feminism over the past 275 years, one constant theme has been feminism’s multidimensionality and intersectionality. Too often, world history textbooks present feminism and the struggle for women’s rights as primarily concerning the right to vote. I’ve emphasized that global feminism has addressed far more issues. Late twentieth-century feminism’s intersectionality was most evident in 1975.

The United Nations designated 1975 as International Women’s Year, focusing on equality, development, and peace. The UN also sponsored the First International Women’s Conference in Mexico City in June 1975. This two-week conference brought together women (and men) from around the world to find common cause and develop a set of policies reflecting the three themes of the year. The United Nations has a short video, “Opening a Global Dialogue on Gender Equality,” on the conference. It’s an excellent resource to introduce the conference.

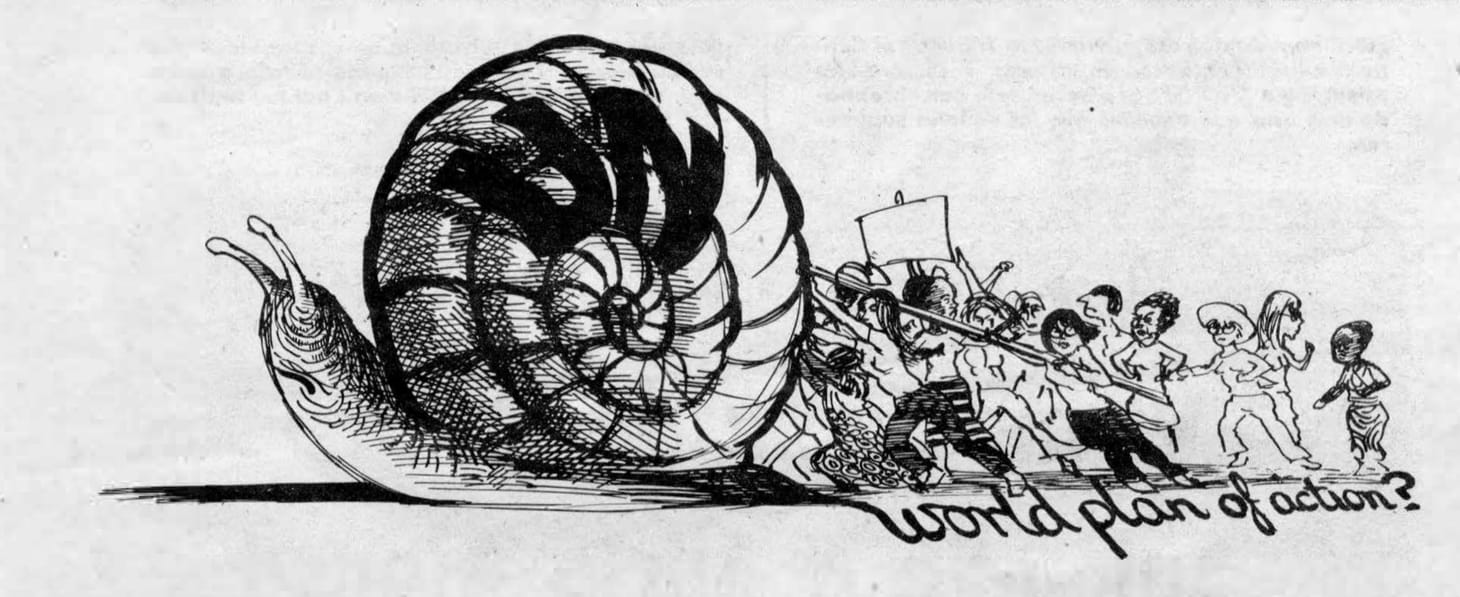

For world history teachers, the Mexico City conference is the ideal case study for teaching late twentieth-century global feminism. Jocelyn Olcott’s International Women's Year: The Greatest Consciousness-Raising Event in History is an excellent resource for teachers wanting to know more about this conference. The diversity of participants highlights the variety of ideas about what feminism is. We can also clearly see how competing global visions of First World capitalism, Second World communism, and Third Worldism shaped different understandings of feminism. Even though the conference participants frequently disagreed and interpreted feminism differently, their coming together for a single conference with participants from around the world reflects the importance of new international organizations and how new technology facilitated increased interaction.

What was American Feminism in 1975?

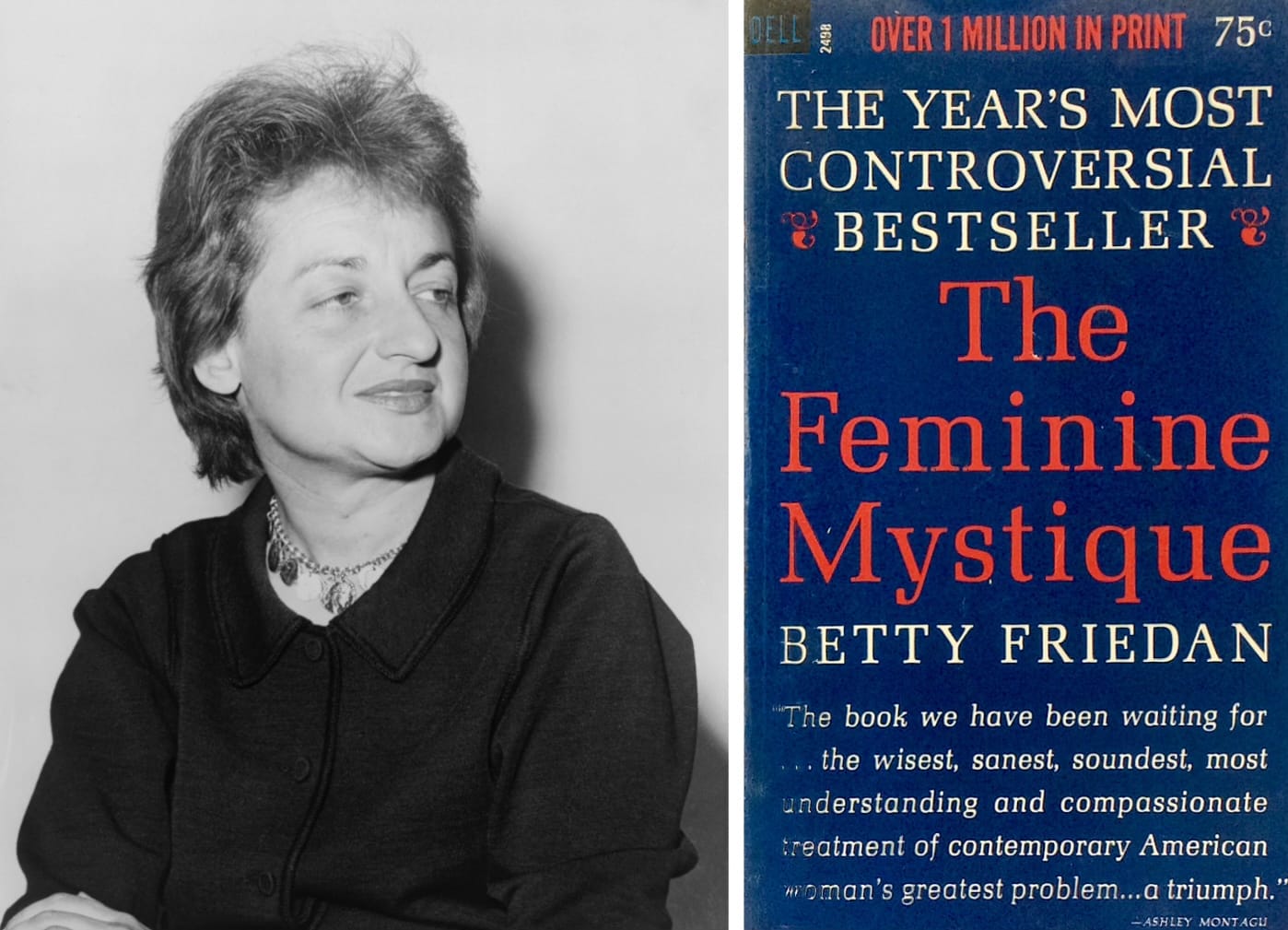

For many students we’re teaching, 1975 is the distant past. As teachers, we need to remind ourselves that our students don’t remember late twentieth-century American history or the Cold War the way we do. Before discussing the First International Women’s Conference, I want to provide some resources to help students first understand the complexity of feminism within the United States. World history textbooks frequently include Betty Friedan as the first example of late twentieth-century Western feminism. Historians of American feminism refer to this period as second-wave feminism. The success of The Feminine Mystique turned Friedan into a global icon of feminism in the 1960s. Susan Hartmann has published an excellent short essay about Friedan and her work on Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective that is ideal for students. Friedan wrote for and about middle-class White women. Her understanding of feminism focused on how middle-class White women balanced family life with the rest of their lives. In 1966, she co-founded the National Organization for Women (NOW). Friedan also fought for the Equal Rights Amendment.

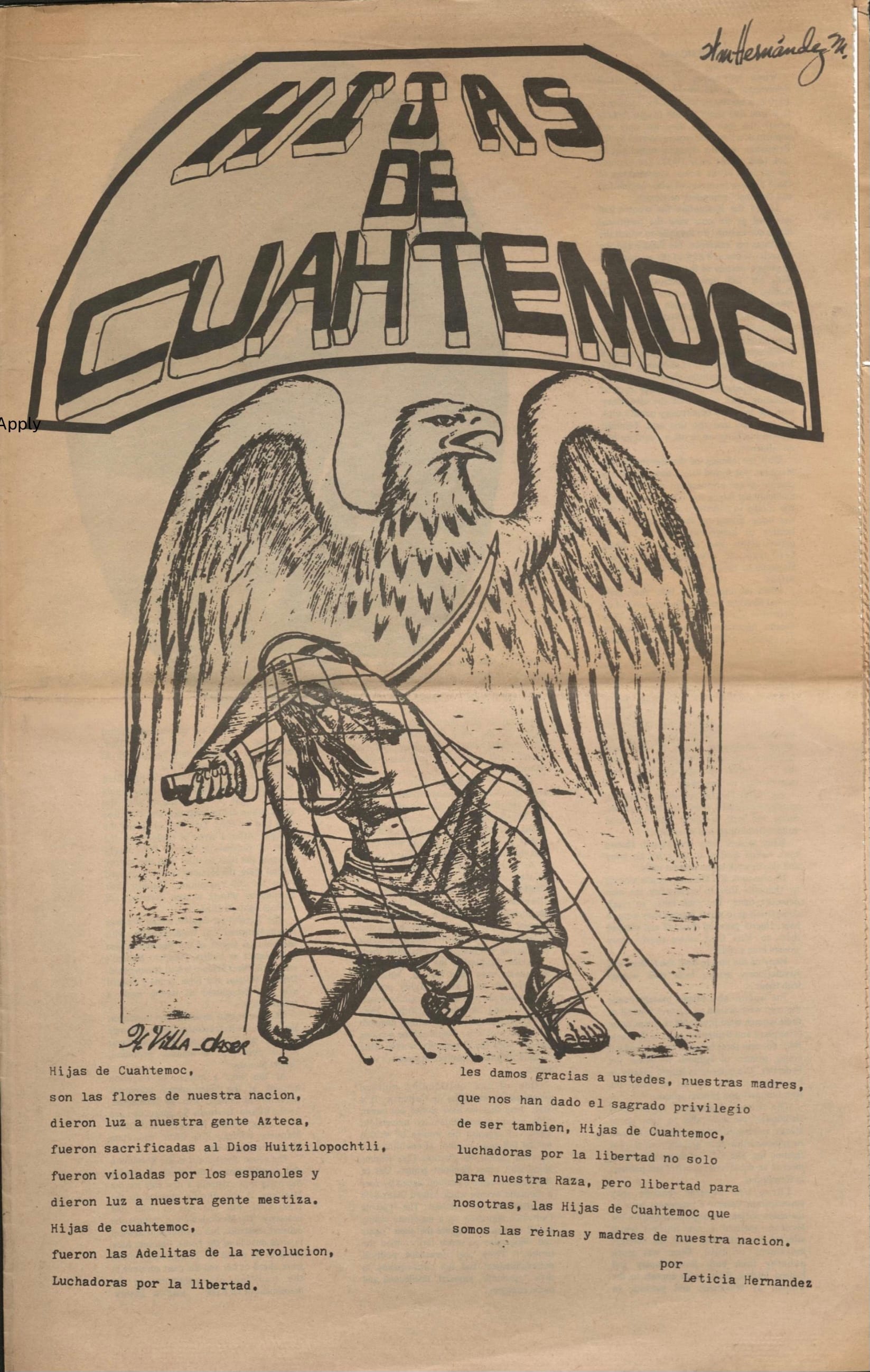

Despite Friedan’s popularity, other American women put forth alternative visions of feminism in the 1960s and 1970s. Women of color and working-class women developed their own understanding of feminism that blended their class, racial, and ethnic identities with gender issues. A good example is Mexican American women developing Chicana feminism in the 1970s. Students in Long Beach, California published the first issue of Hijas de Cuauhtémoc (The Daughters of Cuauhtémoc) in 1971. Cuauhtémoc was the last Aztec Emperor. They explored feminist concerns from a working-class Mexican American perspective.

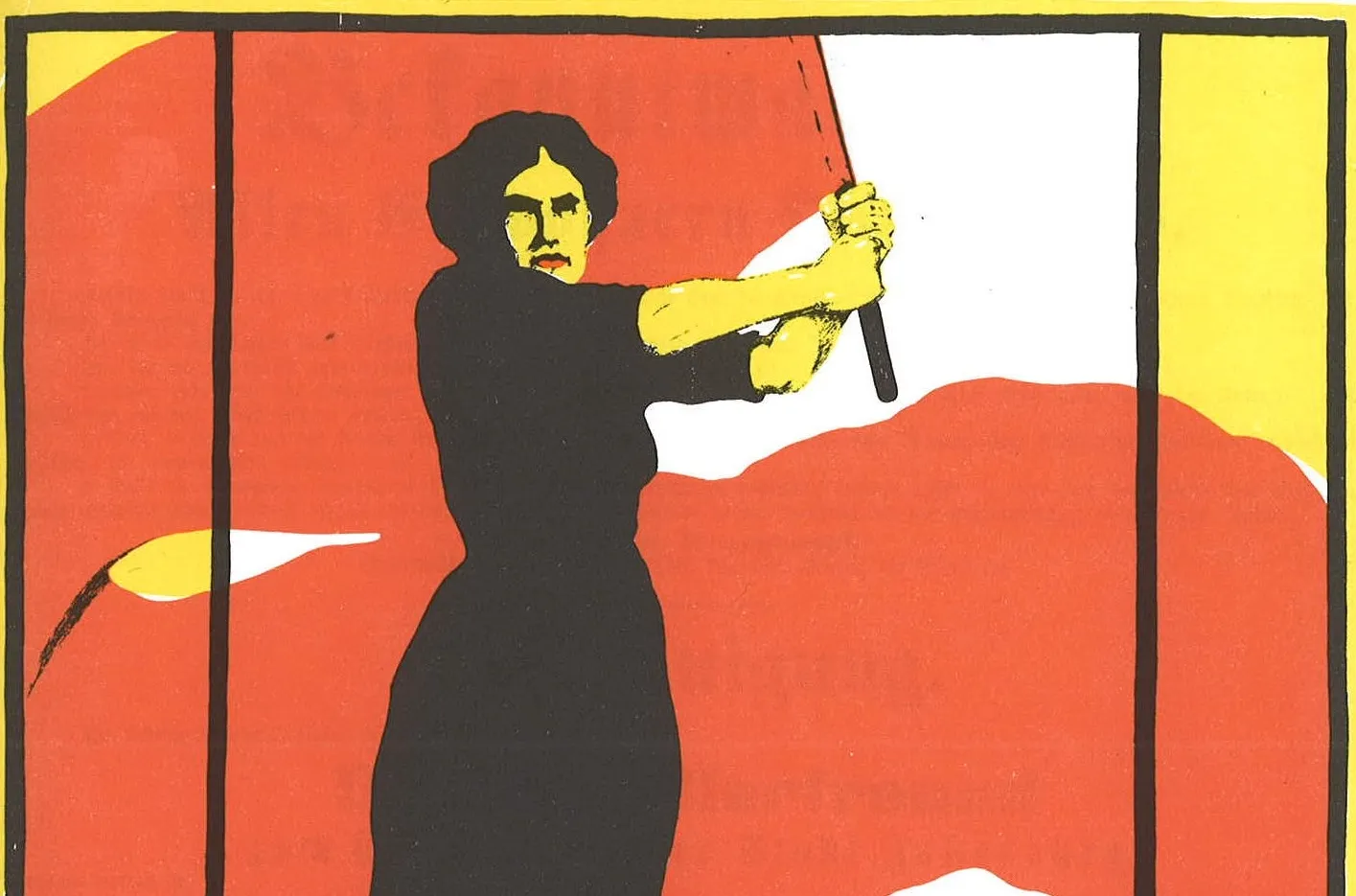

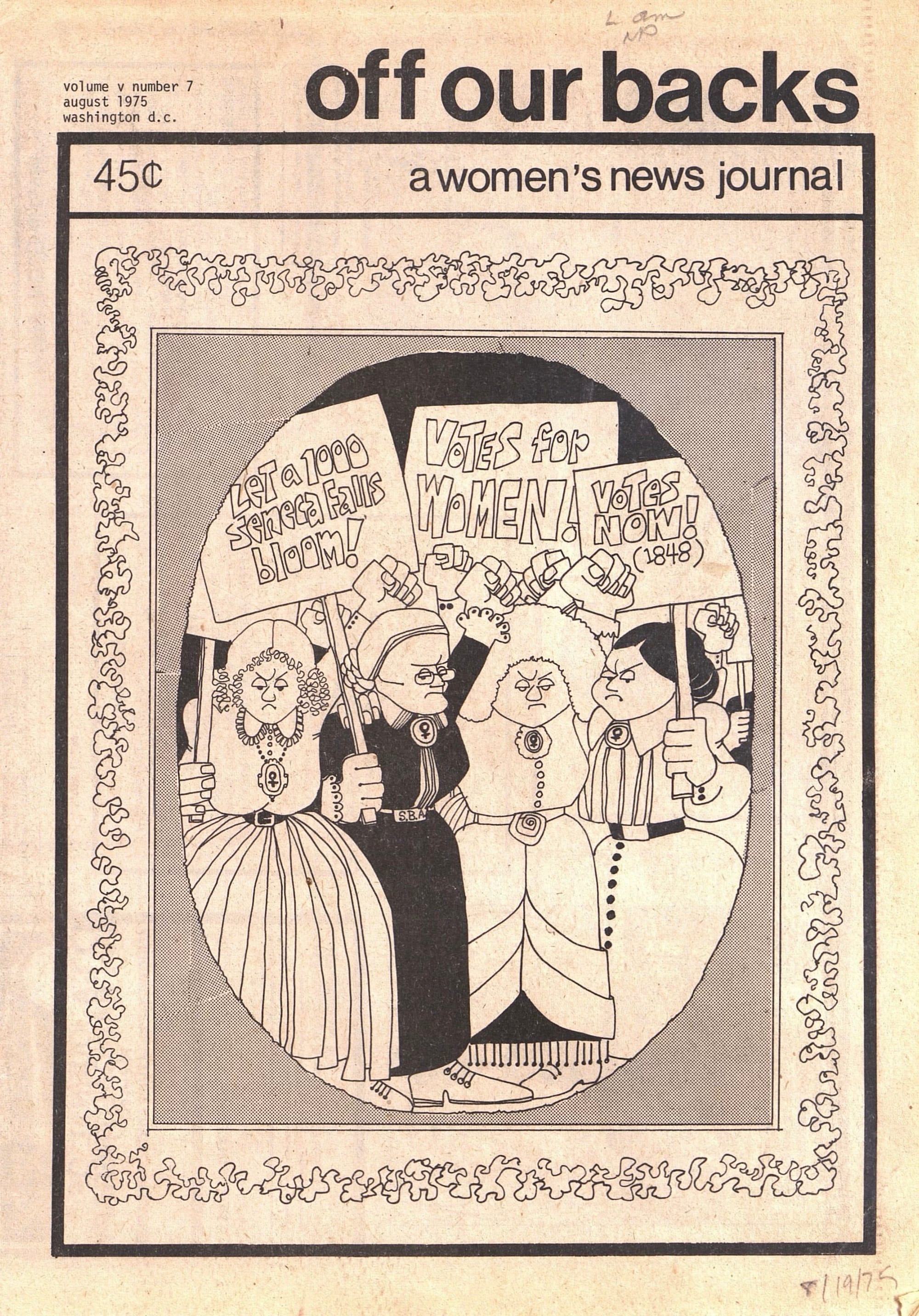

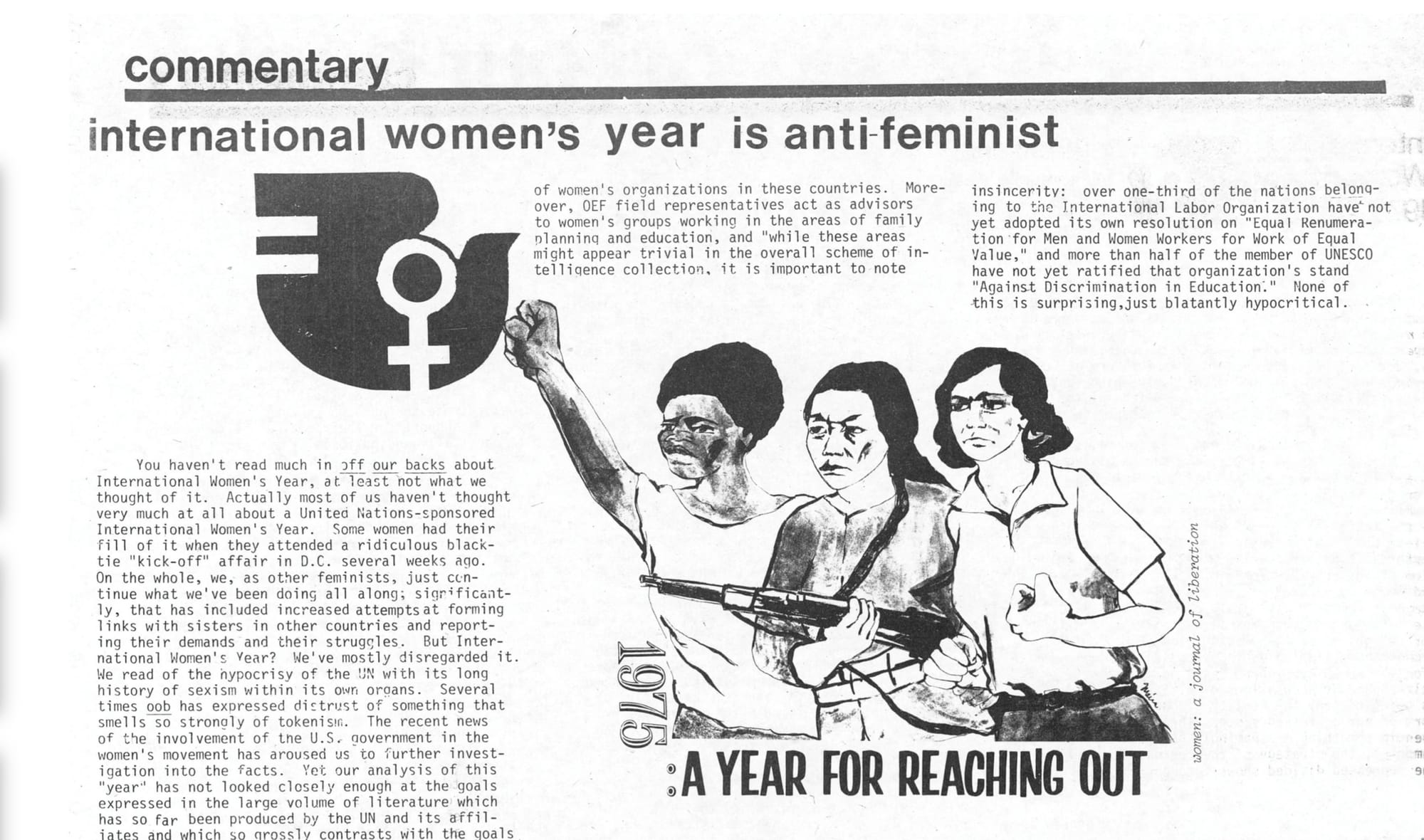

Left: Cover of Hijas de Cuauhtémoc, Vol. 1 (1971) Source: National Museum of American History. Middle: Cover of Off Our Backs, August 1975. Source: JSTOR. Right: Off Our Backs March 1975.

Off Our Backs was a radical feminist journal in the 1970s that focused on lesbian culture and social justice issues. Writers for Off Our Backs often criticized other feminists, such as Friedan, for not being feminist enough. In the March 1975 issue, Marlene Schmitz published an extended essay, “International Women’s Year is Anti-Feminist.” She argued that by attempting to broaden the idea of women’s issues to include development and peace, the International Women’s Year was “the antithesis of that of international feminism.” Off Our Backs and Hijas de Cuauhtémoc illustrate the broader spectrum of American feminism in 1975.

As the most recognizable face of American feminism in 1975, Betty Friedan planned to attend the Mexico City conference. In a revealing letter to Gerald Walker, the New York Times Magazine editor, Friedan claimed “the women’s movement for equality, which began in the U.S. a dozen years ago with my book, is now spreading worldwide” and that she was “battling the male establishment of the Communist and Third World (Arab, Africa, Latin America) and, of course, the Vatican.” Friedan saw herself as an “ambassador-without-portfolio for women.” She then explained why Walker should hire her to write about the conference:

I am obviously going to be in the thick of it—out front in the non-governmental Tribune, and privy to the behind-the-scene maneuvering of the official conference, where the new women-politics cuts across the usual lines. At the very least, a kind of journal of my own encounters and reactions (which is probably the best way to write it) will dramatize the common, or different, interests of women in the four worlds, as they meet in large numbers for the first time—and the new political dynamics of womanpower as such confronting, meshing with or crossing the usual power interests… The modern women’s movement did begin in America—but when I’m asked to help women organizing in their own countries—or in Mexico—am I an agent of American imperialism?

This letter can help students understand the issues with focusing solely on Friedan as an example of late-twentieth-century feminism. While she was well known, she also saw herself as the person to lead the fight for feminism worldwide.

Despite Off Our Backs’ earlier questioning of the feminist credentials of the International Women’s Year, Charlotte Bunch and Frances Doughty, representatives for the National Gay Task Force (now known as the National LGBTQ Task Force), published “IWY - Feminist Strategy for Mexico City” in the May 1975 issue. They explained how the conference would be organized and the danger of too many American feminists attending. As if they had read Friedan’s letter, they provided this advice:

Most importantly those who go (and some lesbian/feminist presence is important) should keep in mind that all Americans' are from an imperialist country and our behavior, even as feminists, often reflects that.

They also provided this closing advice:

Feminists should go to listen as much as to show the world what our idea of feminism is. We should take the time and opportunity to listen closely to what women of other countries tell us about their lives—both their oppressions and strengths. Those strengths are often ones that have been socialized out of most white, middle class women, and we, therefore, often fail to recognize them in others.

If feminists attend the Tribune with such a consciousness and if the number of Americans is not totally overwhelming, there should be many chances to learn and to share our politics, experiences, and insights with other women. Without this consciousness, we play into the hands of U.S. imperialism and confirm the stereotype of the arrogant American. Men around the world already use the stereotype to denounce “women's lib” and to keep “their women” divided from us. We must show the women themselves that we are not simply feminist American chauvinists and then some real learning and exchanges can take place.

Bunch and Doughty recognized the diversity of American feminism. They also understood how other people conference participants might perceive American feminists. But the final sentence suggests they still had a singular vision of what feminism was in 1975. They were not suggesting that American feminists listen closely and modify their own understanding of feminism. For Bunch and Doughty, listening closely was more of a strategy to explain feminism more easily to women from other parts of the world.

Global Visions of Equality, Development, and Peace

This content is for Paid Members

Unlock full access to Liberating Narratives and see the entire library of members-only content.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in