“No Day Passed Without Many Deaths”: Teaching Twentieth-Century Genocides and the War Against Humanity

Discussion of the Herero and Nama Genocide and the teaching of twentieth-century genocides.

Thank you for subscribing to the free Liberating Narratives newsletter. Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to support independent, advertising-free teaching materials.

Teachers often give diplomatic answers about not having “favorite” students, but we all remember certain groups more than others. My first class of tenth-grade modern world history students at Friends Seminary was a naturally curious bunch. By the year’s final quarter, they wanted to shake up our curriculum. Instead of continuing with a more traditional survey of the twentieth century, we collectively decided to focus on twentieth-century genocides. While I appreciated their interest in shaping the curriculum, it wasn’t the best topic for the final quarter. As we reached the last weeks of school, warm sunny days made another class full of heavy stories about genocide challenging. I was as ready for summer break as they were.

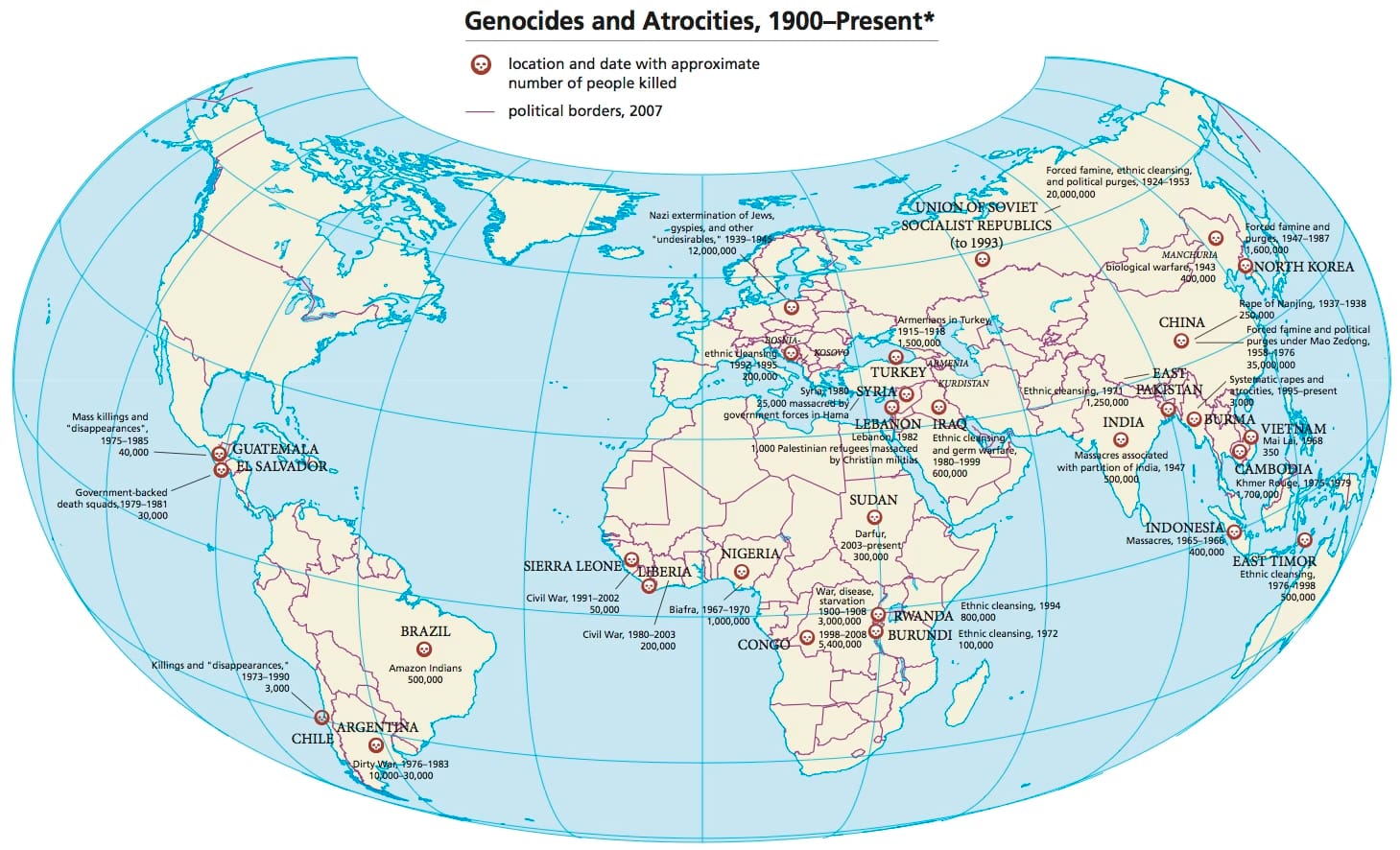

Although I never again focused exclusively on genocides in my world history courses, that experiment helped me realize how many genocides there were in the twentieth century. It wasn’t just the Holocaust, Armenian, and Rwanda (what Professor Jeffrey Bachman, author of “Teaching Genocide,” refers to as the “triad” of twentieth-century genocides); there were more genocides and mass atrocities in just 100 years than I can count on my hands and feet. The map below captures some of the twentieth-century genocides, but not all. That realization made me ask what was different about the twentieth century compared to earlier centuries and how I could help students see this disturbing pattern.

During the next month, I will focus on how we teach twentieth-century genocides in world history surveys. We’ll begin by discussing the challenges and advantages of using the term “genocide.” I will also discuss the Herero and Nama genocide as a case study for developing a few guidelines for regularly integrating teaching genocide in world history surveys.

The Challenge of Defining Genocide

In talking with other teachers and looking at materials on teaching genocide, many colleagues suggest having students learn about Raphael Lemkin , who coined the term genocide, and his work with the United Nations to adopt the genocide convention in 1948. “Raphael Lemkin and the Genocide Convention” is a popular resource on Facing History & Ourselves, one of the most widely used websites for finding resources to teach genocide.

While the Genocide Convention provides a clear legal guideline for defining genocide, it hasn’t prevented further genocides from happening. Genocide Studies scholars have also repeatedly offered their own definitions of genocide. In Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction, Adam Jones includes twenty-five different definitions of genocide developed between 1959 and 2014.

After the first few years of teaching genocide, I stopped having students learn about the legal definition of genocide. It seemed an overly narrow approach to the topic. Given the range of definitions, I felt more freedom as a teacher to approach teaching genocide creatively. I was less concerned with having students know the legal or formal definitions of genocide and more concerned with having students approach learning about genocides as world historians.

Teaching the “War Against Humanity”

World history lends itself to having students work with historical thinking skills, such as comparisons between regions, continuity and change over time, and contextualization. These skills are useful when trying to understand the regularity of genocides and mass atrocities in the twentieth century. Wars dominate twentieth-century political history. Students already study the World Wars and the Cold War. These wars were often also the context for many twentieth-century genocides. Instead of teaching the Armenian Genocide or the Holocaust as unique events, we can situate them with our teaching of the First and Second World Wars.

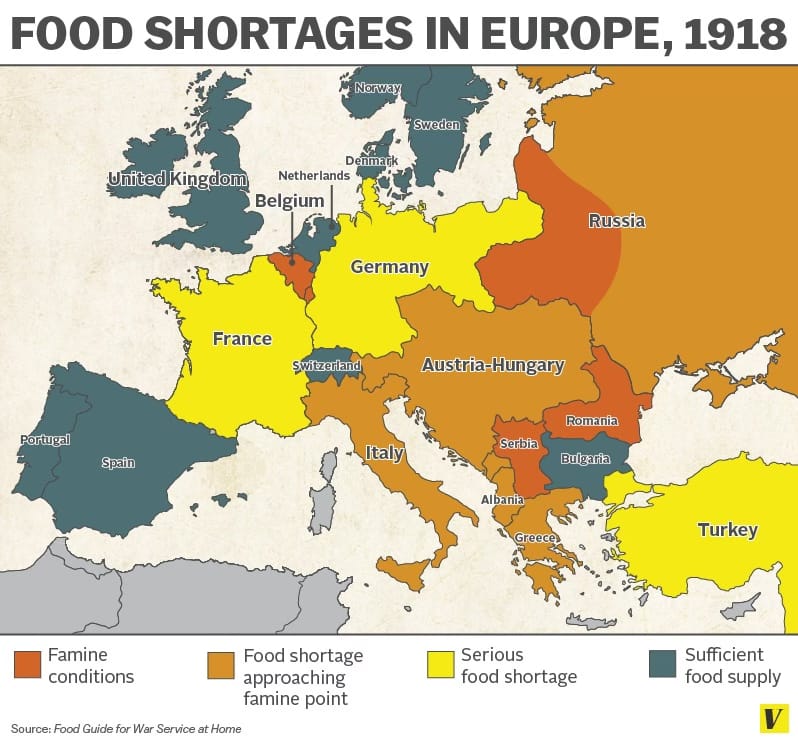

We often teach the concept of “total war” in relation to the First World War. Combatants on all sides regularly targeted civilian populations as enemies. For example, during the First World War, the British and the Germans enacted naval blockades to prevent imports, including basic foodstuffs. Limiting access to food directly targeted civilian populations. The map below shows the extent of food shortages in Europe during the war’s final year. This shift in warfare normalized viewing civilians as legitimate targets during wars, which was critical to understanding the increased number of genocides in the twentieth century.

Students can also apply continuity and change over time to understand how genocides evolved from the Armenian Genocide to Rwanda and the Balkans in the 1990s. While there were critical differences between the major twentieth-century genocides, they also shared many common features. Although the groups of targeted people changed and the methods of killing evolved, governments that committed genocides often used similar methods to justify their actions. It doesn’t matter which genocides students study; they will find the consistent use of dehumanization to rationalize killing specific groups of people.

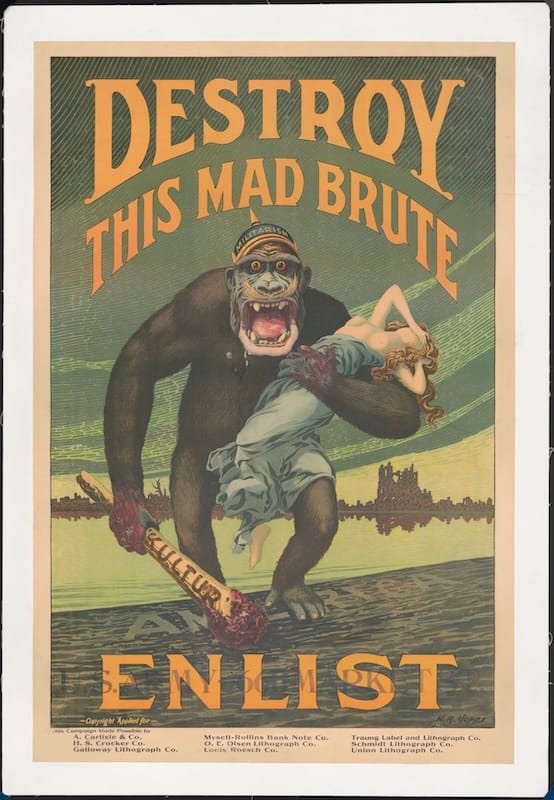

To help students see the connections between these genocides and the context of war, I used the phrase “War Against Humanity” to describe the twentieth century. The wars normalized targeting non-combatants. When we look at these wars, we also see how states used similar dehumanizing rhetoric to portray enemy nations as less than human. For example, the American poster above depicted Germans as animals and “mad brutes.” When students explore the frequency of twentieth-century wars and how they were fought, they are better prepared to analyze genocides.