“Souls are neither Male nor Female”: Teaching Global Feminism in World History, c.1750 to Present

Discussion of teaching global feminism from 1750 to present

Three years ago today, I published my first Liberating Narratives newsletter on teaching the transatlantic slave system. In the years since, I have regularly written posts that amplify marginalized voices and challenge unequal social structures. One topic I haven’t written about enough is feminism. In over 300 published posts, I’ve only discussed feminism four times. When I realized that depressing statistic, I knew I wanted to focus on how we teach feminism in world history. Then something unexpected happened.

As I began gathering resources (websites, books, articles), I noticed that the authors overwhelmingly identify as women. There is the occasional man as a co-author, but they are rare. When I saw this trend, I became self-conscious about writing about feminism. As a White, straight, cis-male, should I write about feminism? Will it seem like I’m mansplaining? I started questioning if I even should write about teaching feminism in world history.

I also reflected on my incredible privilege as a White, straight, cis-male. I need to own my privilege and encourage others who identify as men that we can be models. We can acknowledge that we benefit from a world that men have constructed to benefit men. I thought about my daughter growing up in the United States, where too many men naively believe they are being oppressed and have supported horrific role models, such as Donald Trump, Elon Musk, and Andrew Tate. I can’t single-handedly dismantle the manosphere, but I can at least help teachers teach about how millions of people have consistently struggled to challenge patriarchy and promote equal rights for women. And in doing that, I can amplify the many women authors who have taught me and helped me write these posts.

During the next month, I plan to focus on global feminism from 1750 to today. One of my primary concerns is providing resources that show how women (and a few men) around the world consistently challenged patriarchy (it wasn’t something that only Western women did). In this post, I want to briefly highlight some brilliant early modern women who challenged patriarchy with their writing, discuss the difference between teaching women in world history and teaching global feminism, and illustrate the importance of adopting an intersectional perspective.

Thank you for subscribing to the free version of Liberating Narratives. Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to gain access to more posts like this one and support independent curriculum development.

Subversive Women in the Early Modern World

As long as there have been men constructing a patriarchal society, there have been women who pushed back. The historical record is full of examples of powerful women who challenged the proscribed gender roles of the societies they lived in. They rarely have left behind primary sources describing what they believed or why they acted, but we can catch glimpses. One of the best resources for learning about these women is Bonnie Smith and Nova Robinson’s The Routledge Global History of Feminism. The book contains chapters that provide a broad overview of different historical eras and focus on regions and themes.

In her chapter on “the early modern world,” Merry Wiesner-Hanks surveys how several writers, mostly women, across early-modern Eurasia questioned patriarchy. Even though the early modern world became more interconnected, Wiesner-Hanks doesn’t present these women as feminists or part of a feminist movement. She also excludes the well-known female rulers, such as England’s Queen Elizabeth I or Sumatra’s Sultanah Taj al-Alam, because they “did little to advance the cause of women and – unsurprisingly – rarely critiqued existing structures of power.” Instead of beginning with these “bad-ass women,” I want to start by highlighting four women writers whose works reflect a clear desire to challenge patriarchy.

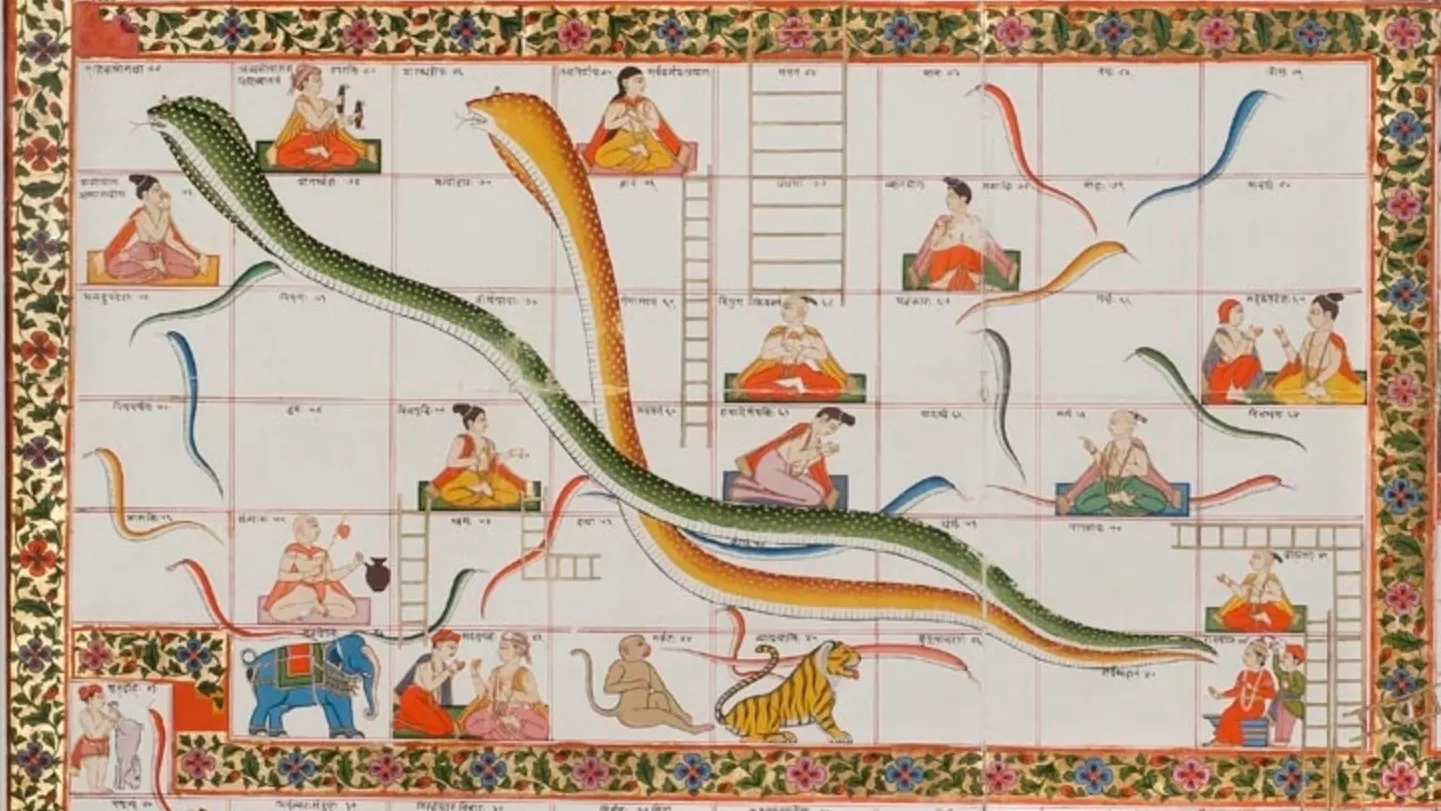

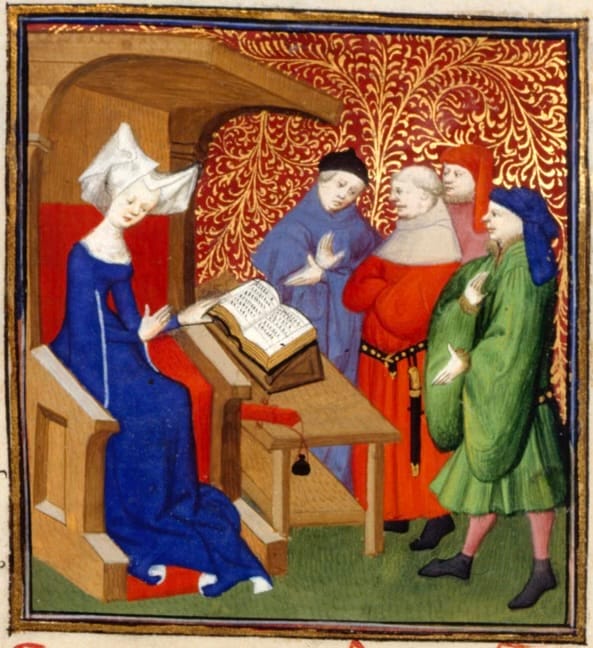

Christine de Pizan lived in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. She was born in Venice and lived at the French court. Pizan also wrote Le Livre de la Cité des Dames (The Book of the City of Ladies) in 1405, describing an allegorical city of ladies. She included many famous women and discussed the lack of education available to women. The image above comes from The Queen’s Manuscript of The City of Ladies in the British Library. Christine de Pizan is in the blue dress, sitting in front of a book, discussing or debating with four men.

Two centuries later in Spain, María de Zayas y Sotomayor wrote Exemplary Tales of Love, a novella about a group of women telling stories about romantic encounters. In the introduction, Zayas challenges the reader to consider why more women haven’t published books:

Who doubts, my reader, that you will be amazed that a woman has the audacity not only to write a book, but to send it for printing, which is the crucible in which the purity of genius is tested…. But anyone, provided that person be no less than a good courtier, will neither find it a novelty nor gossip about it as idiocy. Because if this material of which we men and women are made, whether a combination of fire and mud, or a mass of spirits and clods, is no more noble in them than in us, if our blood is the same thing, our senses, faculties, and organs through which their effects are wrought are all the same, the soul the same as theirs—since souls are neither male nor female—what reason is there that they would be wise and presume we cannot be so?

This has, in my opinion, no other answer than their impiety or tyranny in locking us up and not giving us teachers. And so the true reason why women are not learned is not a lack of ability but lack of practice. Because if in our upbringing…. they were to provide us with books and preceptors, we would prove as apt for posts and professorships as men.

Students can see that Zayas is questioning society’s inequality, which allows more men than women to receive an education. This lack of education, rather than ability, is why few women publish books. Zayas directly challenged patriarchy and even suggested that women with an education could do the same jobs as men.

In fifteenth-century Anatolia, Mihrî Hatun was a poet who subtly challenged expectations about women poets. Unlike Zayas, Hatun didn’t directly question the unequal educational opportunities. She mainly wrote poems that Ottoman elites and scholars enjoyed, but occasional poems challenged patriarchy. In one poem, Hatun challenged stereotypes about women:

Since they say women lack reason

All their words should be excused.

An efficient woman is much better than

A thousand inefficient men.

By focusing a person’s value not on their gender, but on their “efficiency,” Hatun pushed back against claims of women’s inferiority. Hatun wrote hundreds of poems, and later Ottoman authors praised her work.

In the late 1600s in Korea, Queen Inhyeon was the wife of King Sukjong of the Joseon dynasty. She became one of the most well-known Korean queens. Many Korean authors wrote dramas about her life. One of those dramas is The True History of Queen Inhyon by an unidentified author. JaHyun Kim Haboush, a specialist in South Korean literature, argues that the author was most likely one of the queen’s ladies-in-waiting. Haboush claims that the unknown author subtly subverted Confucian stereotypes about women, which suggested they were emotional and should therefore submit to the will of their husbands and fathers. In the novel, the unknown author presented Inhyon as more rational. Haboush argues that

Inhyon is strongly self-possessed, exercises autonomy of emotion instead of repressing it, and takes control of her destiny from the options available to her. She is distinctly an ideal constructed by and for women. The dignified image of a woman who exercises completely rational judgment must have had a tremendous appeal to women readers.

Although we don’t know the author of The True History of Queen Inhyon, we can see parallels between her and the three other women I’ve discussed. All of them used literature to challenge patriarchal stereotypes about women. While none of them called for remaking society and equal opportunities for women, they were pointing out how patriarchy affected women.