“We Ladies of Africa”: Feminism, Socialism, and Imperialism, c.1850 - c.1910

Teaching late nineteenth-century global feminism

Every March in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, we celebrate Women’s History Month. If you’ve ever wondered why Women’s History Month happens in March, it’s because March 8 is International Women’s Day. Over twenty-five countries and the United Nations officially recognize the holiday, but the three countries that celebrate Women’s History Month don’t recognize it.

You might be scratching your head at this puzzling disconnect, but it makes more sense when we look at the holiday’s origins. Most historians agree that the Socialist Party of America organized the first “Woman’s Day” in New York City in 1909. The following year, at the Second International Socialist Women’s Conference in Copenhagen, Clara Zetkin proposed that the first International Women’s Day be celebrated in 1911. On March 18, 1911, over a million Austrians, Danes, Dutch, Germans, Poles, and Swiss participated in marches and meetings to celebrate the first International Women’s Day.

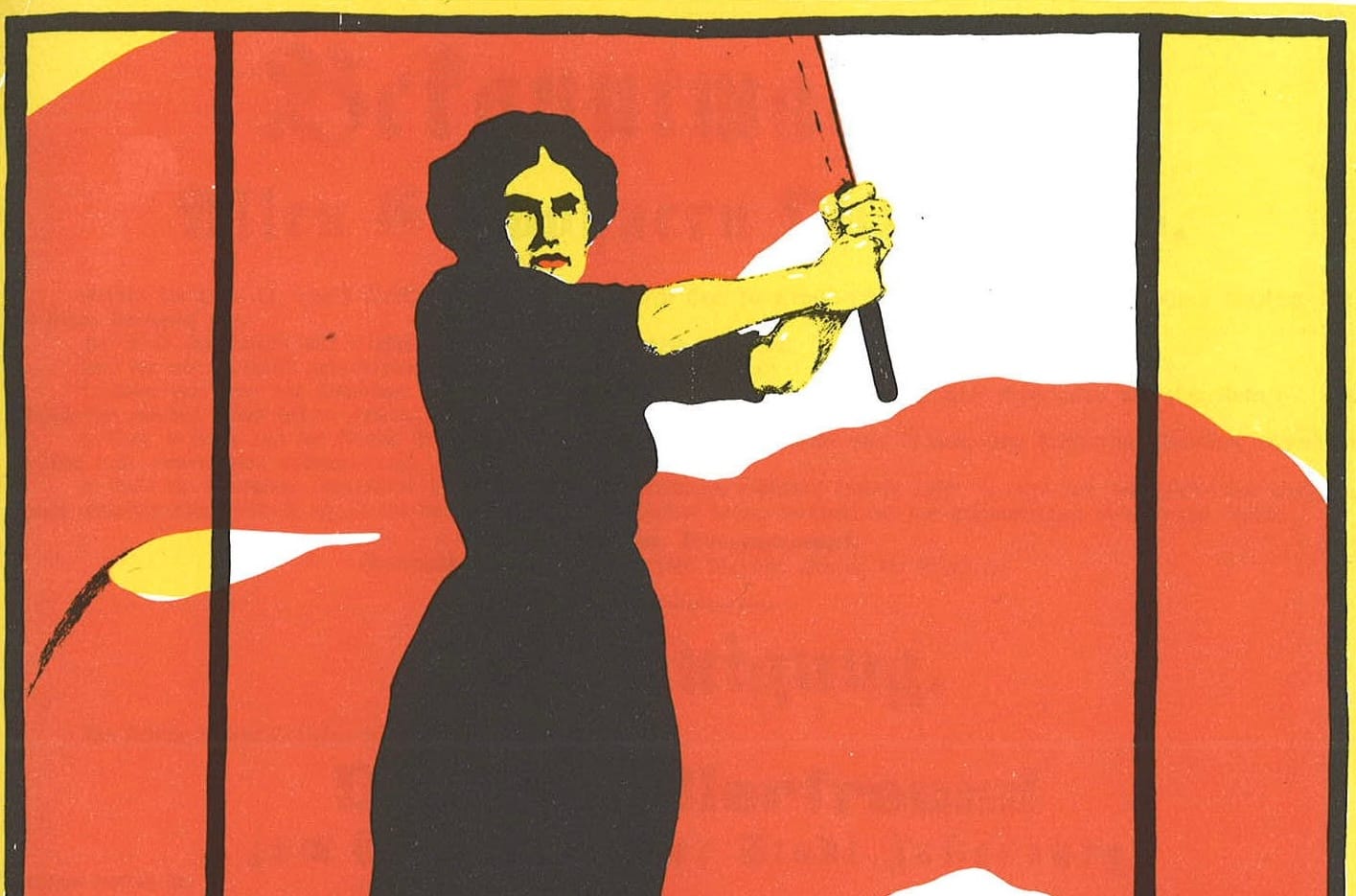

Left: Banned poster for International Women’s Day in Germany in 1914. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Right: Women protesting in Petrograd (St. Petersburg), Russia on March 8, 1917. Source: Guardian.

In subsequent years, the holiday continued to grow in popularity. It spread across Europe. The German government banned the poster above in 1914. Russian women first celebrated the holiday on March 8 in 1913. When women marched in 1917, their protests were critical to the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II. Despite its growing popularity and partial American origins, the United States never recognized the holiday because of its connection to socialism and communism.

Strong anti-communist sentiment in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States seems to have also shaped how we remember feminism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Many women (and some men) who fought for women’s rights and equality saw that struggle as intertwined with the fight for economic justice. However, in the United States and the United Kingdom, the fight for women’s suffrage is a key part of our national narratives, but it is not how feminists fought for economic change. In the late nineteenth century, as the idea of feminism became more widespread, it also developed a complicated relationship with imperialism. By looking at the relationship between feminism and economic justice and how feminism appeared in colonies, we can better understand how late nineteenth and early twentieth century feminism was much more than gaining the vote for women.

The Origins of Feminism

Although there were women and men whom we can call feminists in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the term feminism didn’t emerge until the late nineteenth century. The earliest known uses were in France in the mid-1800s, although the term was associated with “confused” men who supported women’s rights. By the 1890s, Britons began using the term to refer to women fighting for equal rights. The term spread to the United States early in the twentieth century.

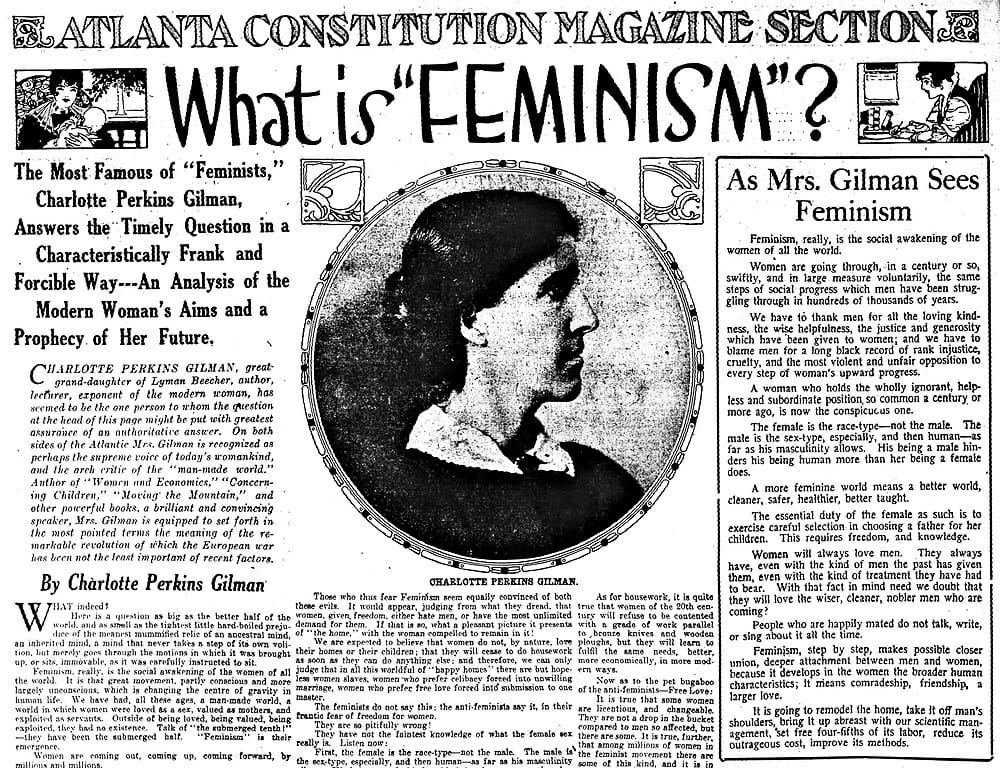

Although we typically refer to feminism as equal rights for women, the meaning has changed over time. In the article above, Charlotte Perkins Gilman described feminism as the “social awakening of women of all the world.” In subsequent paragraphs, she argues that:

A more feminine world means a better world, cleaner, safer, healthier, better taught.

The essential duty of the female as such is to exercise careful selection in choosing a father for her children. This requires freedom, and knowledge.

Most people today probably wouldn’t associate feminism with “careful selection in choosing a father for her children.” This shift in what feminism has meant and where it’s been used as a term is a helpful reminder that global feminism was a broad movement. Although world history textbooks often focus on just a few key issues, such as suffrage and education, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, “feminists” of the period connected feminism to much more. Students need to understand how feminism could be used in different ways.

Global Feminism and Economic Justice

This content is for Paid Members

Unlock full access to Liberating Narratives and see the entire library of members-only content.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in