“You Will Never Stop The Emancipation of Women”: Teaching Global Feminism in the Age of Revolutions, c.1750 - c.1850

Teaching the early development of global feminism from 1750 to 1850

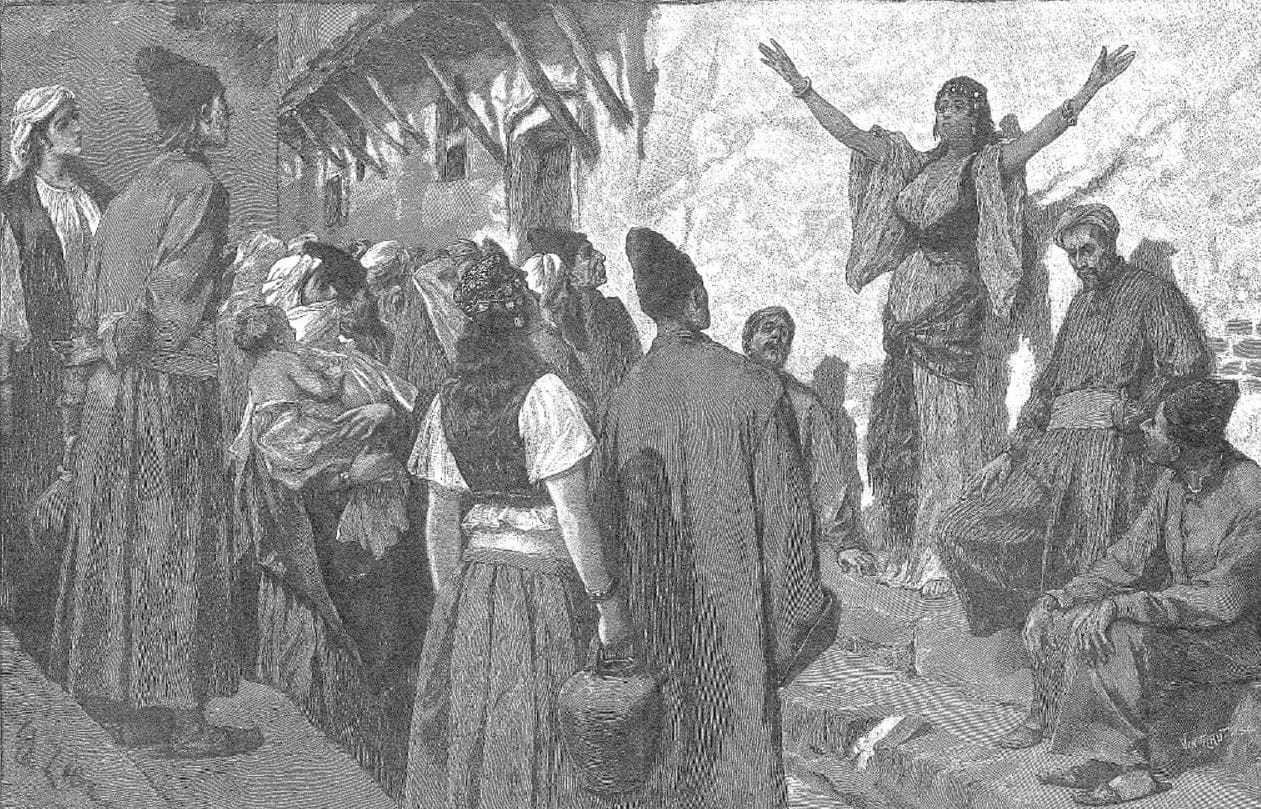

1848 is an important year in the history of feminism. In July of that year, a woman stood before a gathering and argued for the rights of women. You might think you already know about this event, but the woman was not Elizabeth Cady Stanton or Lucretia Mott. The location was not Seneca Falls in upstate New York. The speaker was Fatimah Baraghani, and the setting was Badasht, Persia (present-day Bedasht in northern Iran). She called on the other participants of the gathering to change how Persian society treated women:

Rise, brother, the Qur'an is fulfilled and a new era has begun. Am I not your sister, and you my brother? Can you not look upon me as a real friend? If you cannot put out of your mind evil thoughts [most women in nineteenth-century Persia wore veils], how will you be able to give your lives for a great cause? Are you aware that this custom of veiling the face was not enjoined by Muhammad (peace be upon him) so rigorously as you seem to observe? Do you not remember that in some matters he used to send his disciples to go and ask his wife? Let us emancipate our women and reform our society. Let us rise out of our graves of superstition and egoism and pronounce that the Day of Judgment is at hand; then shall the whole earth respond to the freedom of conscience and new life!

Fatimah Baraghani, who is known as Táhirih, was born a Shia Muslim and had been inspired by ʻAlí-Muḥammad, The Bab. Adherents of the Baháʼí faith today trace their origins to the Bab’s movement and celebrate Táhirih as one of Persia’s first feminists.

In the four years after that speech at Badasht, Táhirih continued to speak regularly about the “rights” of women. She often spoke in public without wearing a veil and challenged polygyny. In 1852, three Babis (followers of the Bab) allegedly attempted to assassinate the Qajar Shah Naser-al-Din. Qajar officials arrested Tahirih on suspicion of being involved in the assassination attempt. In August 1852, they executed Táhirih. Baháʼís claim her final words were “You can kill me as soon as you like, but you will never stop the emancipation of women.”

Although millions of Baháʼís today celebrate Táhirih, few Westerners know who she is or the Baháʼí faith, which promotes the oneness of humanity. I learned of her because a Baháʼí student told me about her. I’ve yet to find a world history textbook that mentions her, although almost all mention the Seneca Falls Convention. The Eurocentric narrative of feminism is pervasive in world history textbooks. Feminism and women’s rights are often introduced in the same chapters as the Enlightenment and the Atlantic Revolutions (although often at the end of the chapter or in a special box). Not all feminist movements originated in the Atlantic world or because of Enlightenment values. Táhirih is an ideal illustrative example to include in a global feminist narrative. In this post, I will discuss how all feminists were shaped by the societies in which they lived and some of the different manifestations of feminism before 1850.

Feminism Has Always Been Intersectional

World history textbooks usually discuss the origins of feminism and women’s rights within the context of the Enlightenment and the Atlantic Revolutions. Because the first White feminists focused primarily on education and suffrage, those became the default feminist concerns. When students learn about feminism outside the Atlantic world, authors often present it as having been spread to the rest of the world by Westerners. As people in different parts of Africa and Asia adapted feminism, they also added their own concerns. In this way, White elite feminism became the default, and other feminist movements are presented as adaptations and being intersectional.

Táhirih’s speech shows how women in other parts of the world pushed back against patriarchy without needing to localize Western feminism. When she criticized women wearing veils, Táhirih didn’t borrow the logic of Western feminism. She looked to examples from the Qur’an and hadith and invoked examples from Muhammad’s life. Táhirih’s idea of the emancipation of women was more concerned with fighting polygyny rather than suffrage.

Just as Táhirih’s feminist concerns reflected the Persian society in which she lived, other nineteenth-century advocates for women’s rights focused on issues that reflected their societies. In the previous post, I discussed Frances Watkins Harper’s 1866 speech “We Are All Bound Up Together.” As an African-American woman, Harper’s feminism was shaped by living in a racist country. She was less concerned about gaining the right to vote and more concerned with fighting racism.

Broader social constructs also influenced White elite feminists in the West. Elizabeth Cady Stanton is the American feminist most associated with the suffrage movement. Her ideas about suffrage were also shaped by the same social context as Harper, but Stanton’s view reflects being a middle-class White woman in nineteenth-century America. She was already in a position of privilege. In 1867, New York State held a constitutional convention to discuss expanding suffrage. Stanton’s views on how suffrage should and should not be expanded reflect living in a racist society as a privileged White woman:

If…. enfranchisement is to be slowly extended in the future as the past, we would suggest that it would be wiser and safer to enfranchise the higher orders of womanhood than the lower orders of black and white, washed and unwashed, lettered and unlettered manhood. Would the gentlemen of the Convention (New York State’s Constitutional Convention of 1867) be willing to stand aside, while boot-blacks, barbers, and ignorant foreigners were placed over their heads to legislate on their interests and those of the State? Certainly not! Neither are wise and thoughtful women willing to see the lowest orders of manhood placed over their heads, while they have no voice in their own personal interests or the welfare of the nation. When we remember that with exclusive manhood suffrage, we have such wholesale corruption and fraud in our halls of justice and legislation, with rumholes, gambling saloons and brothels on every corner of our cities—with filthy streets, tenement-houses, markets and prisons; when we look at our whole criminal legislation, at our pauperism, imbecility, and crime, at the 40,000 drunkards' wives in this State, ragged and gaunt—victims of our laws. When we look on all these wrongs, and remember that they are noted up or down, who does not see the need of some new element in our legislation? What Woman does not see the power of the ballot in clearing up this great wilderness of life, and feel that it is her duty to demand it, and use it for the good of the race?

Stanton’s views on suffrage reflect already being in a position of relative power. She may not have been able to vote in the same ways as elite White men, but she still saw herself above working-class Americans and recent immigrants. She supported expanding the vote, but not in a way that might undermine her racial and class privilege. Stanton’s advocacy of limiting expanded voting rights only to “the higher orders of womanhood” reminds us that feminism was always intersectional. Elite White women also allowed their social context to shape how they defined feminism. In the case of Stanton, giving certain White women the right to vote would be “for the good of the race.”

As we teach global feminism, we must be mindful of not presenting elite White feminism as the norm and all other types as adaptations. To help students understand the diverse concerns of early nineteenth-century feminists, we should integrate examples of how other feminists were influenced by different social concerns.

Broadening our Understanding of White Feminism

This content is for Paid Members

Unlock full access to Liberating Narratives and see the entire library of members-only content.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in