“A Great City”: Akbar and Fatehpur Sikri

A discussion of how to use paintings of Fatehpur Sikri to teach about the Mughal Emperor Akbar.

If Babur, whom I discussed in last week’s post, is the emperor many world history teachers tend to gloss over while teaching the Mughals, Akbar is the emperor whom teachers most focus on. He established the Mughal Empire as a major power in the sixteenth century. Akbar ruled for almost fifty years. During his long reign, he expanded the Mughal Empire from a regional state around Delhi to a massive empire ruling over northern India.

Akbar was more than just a conqueror; he completely transformed how the Mughal Empire worked. In India in the Persianate Age: 1000-1765, Richard Eaton describes the legacy of Akbar for Mughal India:

By the time of his death in 1605, Akbar was able to bequeath to his son Salim a consolidated state with well-ordered administrative institutions and a hybridized ruling ideology suited to India’s diverse society.

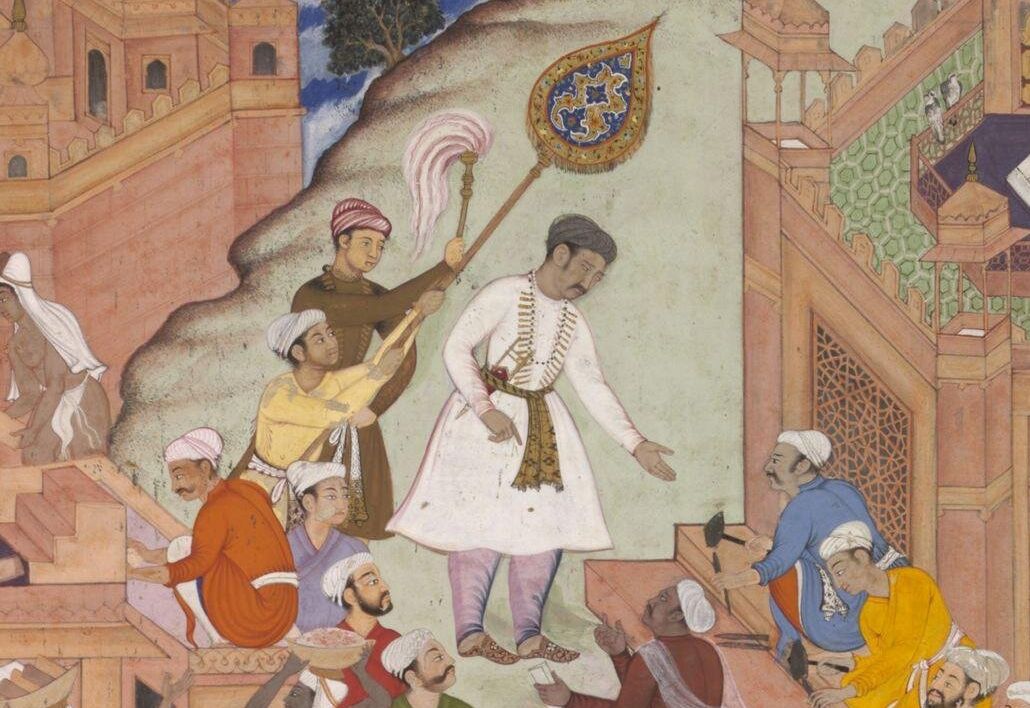

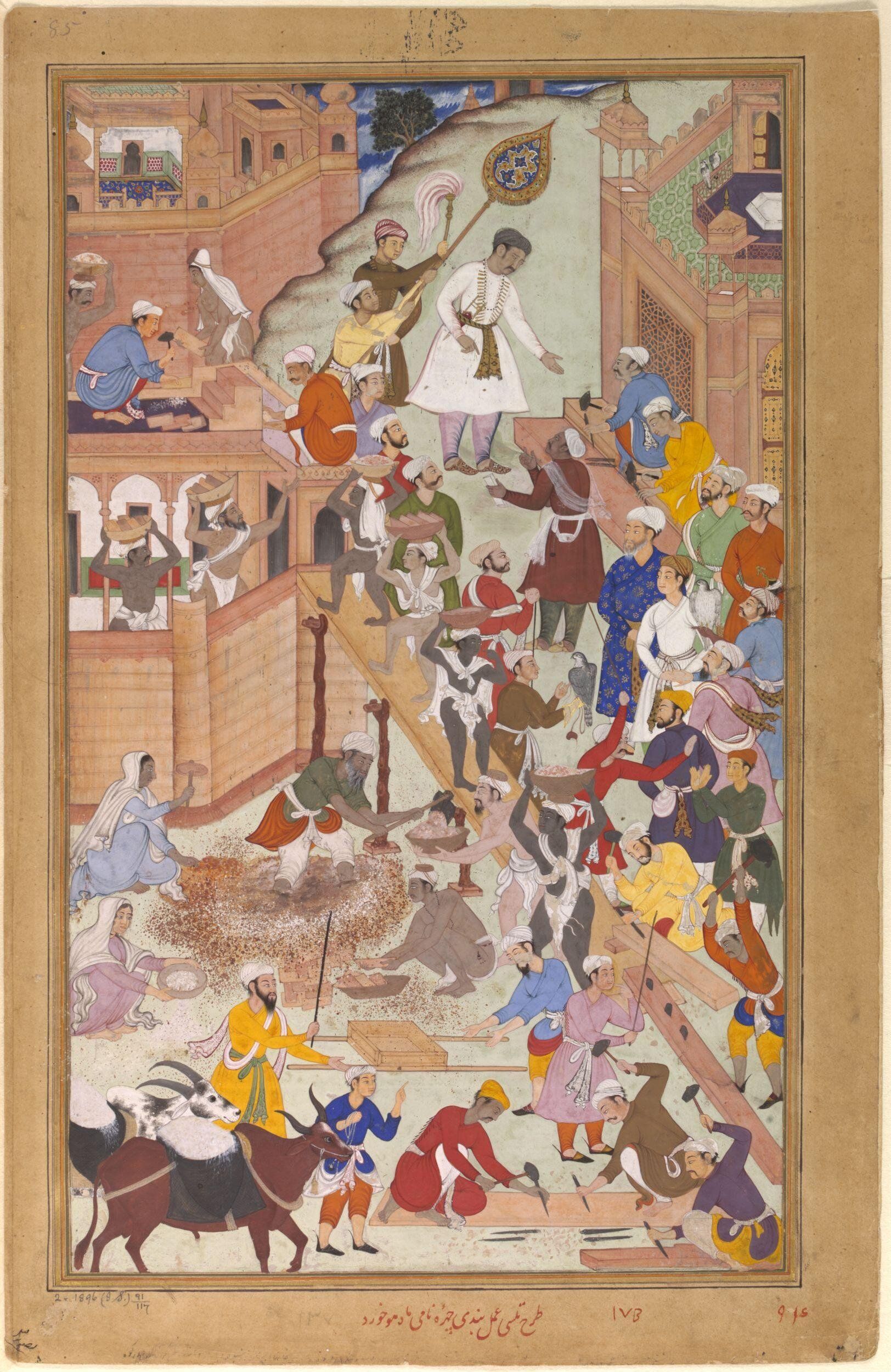

No single image of the Mughal Empire can help students understand all these aspects of Akbar, so I will focus primarily on Akbar’s “hybridized ruling ideology” by exploring two related images of the construction of Fatehpur Sikri. These images appear in the Akbarnama, and they help students understand both the Timurid and Indian influences on the Mughal Empire.

Building Fatehpur Sikri

When Akbar became emperor in 1556, his first capital was Agra. In the 1570s and 1580s, Akbar moved the capital to Sikri. After victories in Gujarat in 1573, he renamed the city Fatehpur (“Town of Victory”) Sikri. Akbar most likely chose Sikri to be the site of his new capital because of its connection to the Sufi saint Salim Chishti, who had predicted Akbar would soon have a son.

This content is for Paid Members

Unlock full access to Liberating Narratives and see the entire library of members-only content.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in