“Merchants From All Quarters”: The Indian Ocean Exchange Network, c.1000 - c.1500

Discussion of how to teach the Indian Ocean exchange network between 1000 and 1500 C.E.

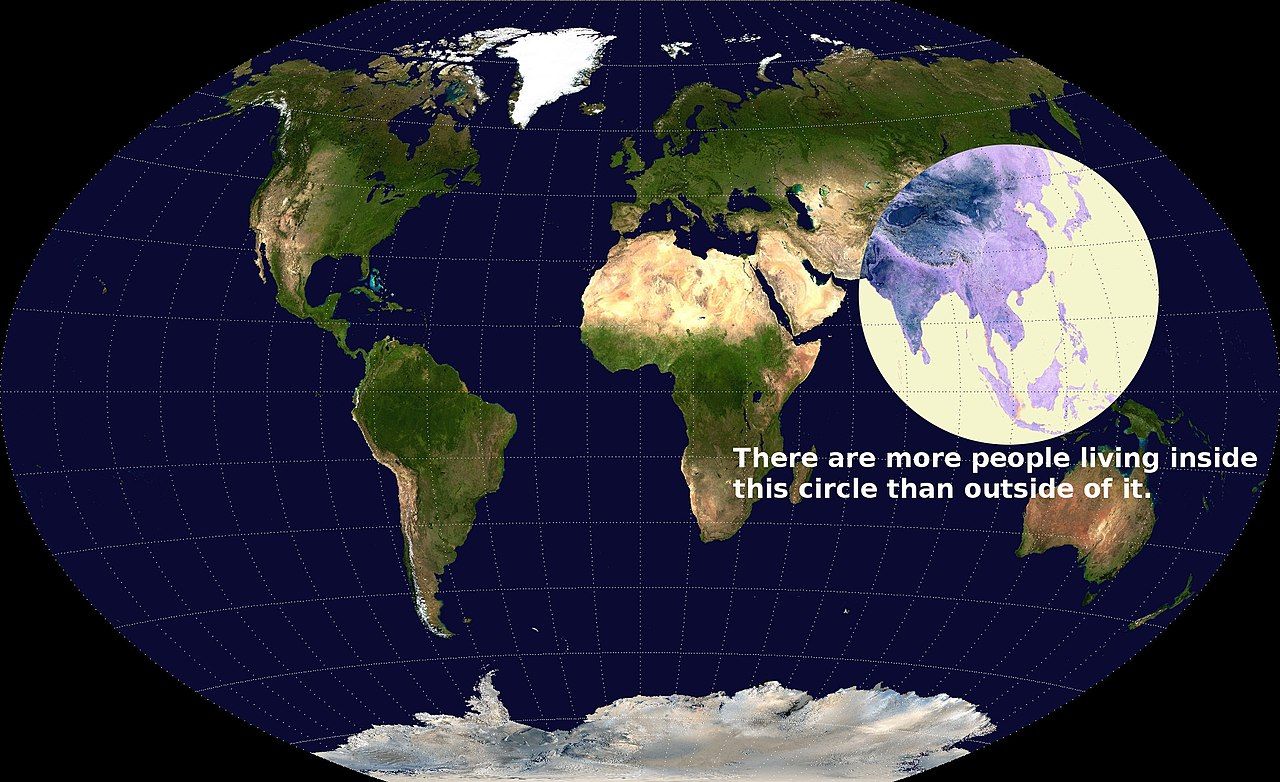

Of the three major oceans (Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific), the Indian Ocean is the smallest in square kilometers. Despite being geographically smallest, it may be the most complex to teach, given how much of the world’s population has historically lived around its shores. One of the easy ways to help students begin to visualize the size of the population of the Indian Ocean exchange network is using the Valeriepieris circle. Over half of the world’s current population lives within an area covering about two-thirds of the historic Indian Ocean Exchange Network.

In 1000, the world’s population was less than 5% of the world’s population today. We can see from historical population estimates that the greater Indian Ocean was also one of the most densely populated areas of the planet even then. The three largest states were the Song Dynasty in China and the Chola and Pala Empires in India. These three states were almost 30% of the world’s population in 1000. The Valeriepieris circle is as much a historical phenomenon as a contemporary one. The concentration of people living in the Indian Ocean 1,000 years ago means the amount and variety of exchange were more extensive and complex than in the Atlantic Ocean or Mediterranean exchange networks.

Given the size of the population of the greater Indian Ocean, the challenges of teaching the Indian Ocean exchange network are the same as teaching world history. We want to provide both a big-picture understanding and individual stories. Students need to understand the large-scale patterns that shaped exchange in the Indian Ocean, but they also need personal stories to provide texture and depth. By focusing on a few key individuals and important port cities, we can help students understand the complexity of the Indian Ocean exchange network even before Europeans arrived 500 years ago.

The Big Picture: Mapping and Visualizing a Network from Africa to China

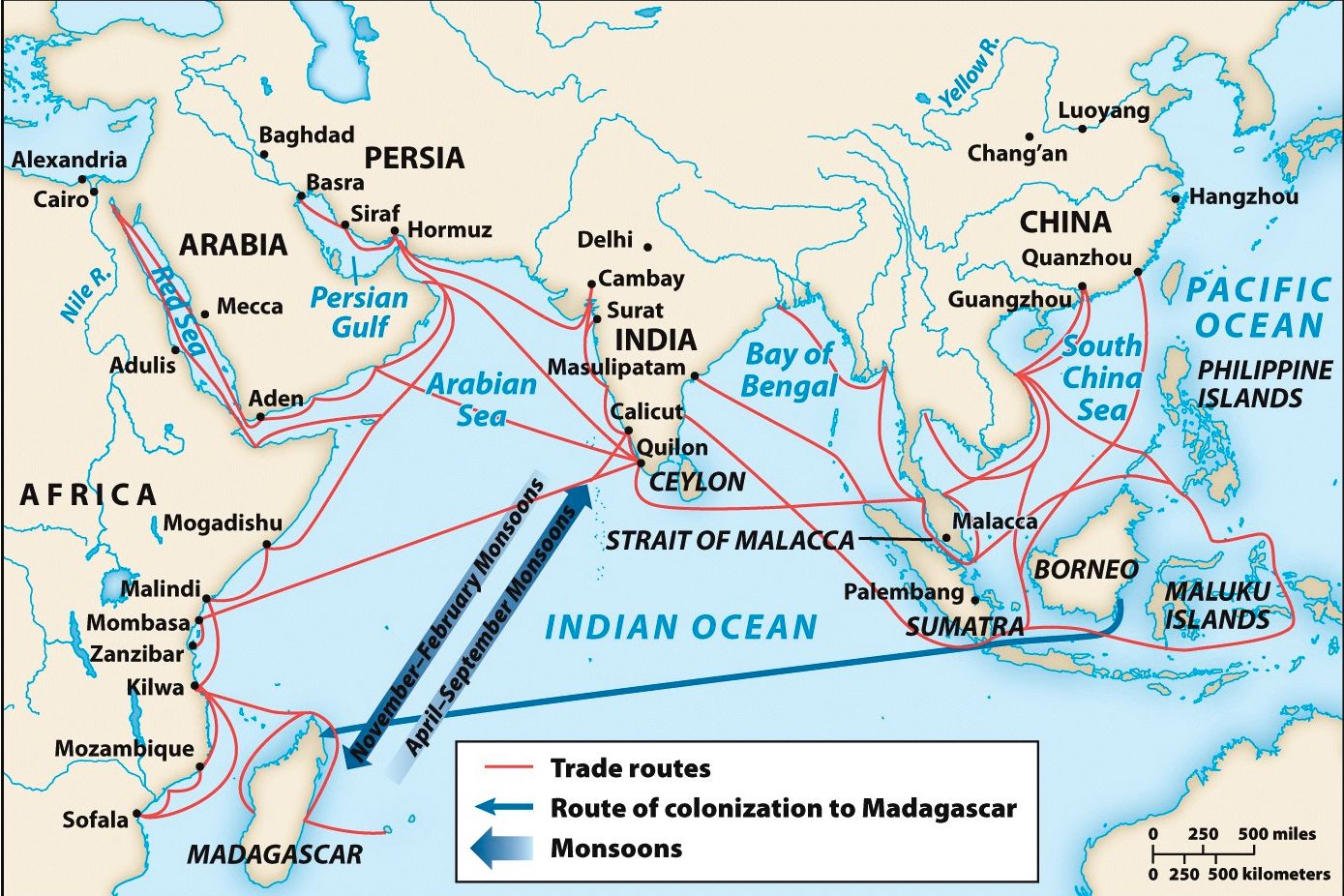

When we discuss the Indian Ocean exchange network, we are describing a system stretching from Africa’s east coast to northeastern China. The critical feature linking people across this space was the “monsoon.” Before the development of steamships, railroads, and airplanes, monsoons made the Indian Ocean one of the most efficient trade routes in the world. Monsoon is often used as a shorthand for the seasonal winds, the patterns of rainfall, and the currents around the Indian Ocean. Looking at the map above, students can quickly understand how strong seasonal winds benefitted sailors by allowing them to sail with the winds and travel faster over longer distances.

This content is for Paid Members

Unlock full access to Liberating Narratives and see the entire library of members-only content.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in