“To Destroy the Colonial World”: Teaching Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth and Decolonization

Discussion of teaching Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth when teaching decolonization.

In last week’s post, I mentioned that Frantz Fanon had also written The Wretched of the Earth before discussing an excerpt from Toward the African Revolution. As soon as I finished that post, I knew I needed to say more about the importance of The Wretched of the Earth when teaching world history from a decolonized perspective.

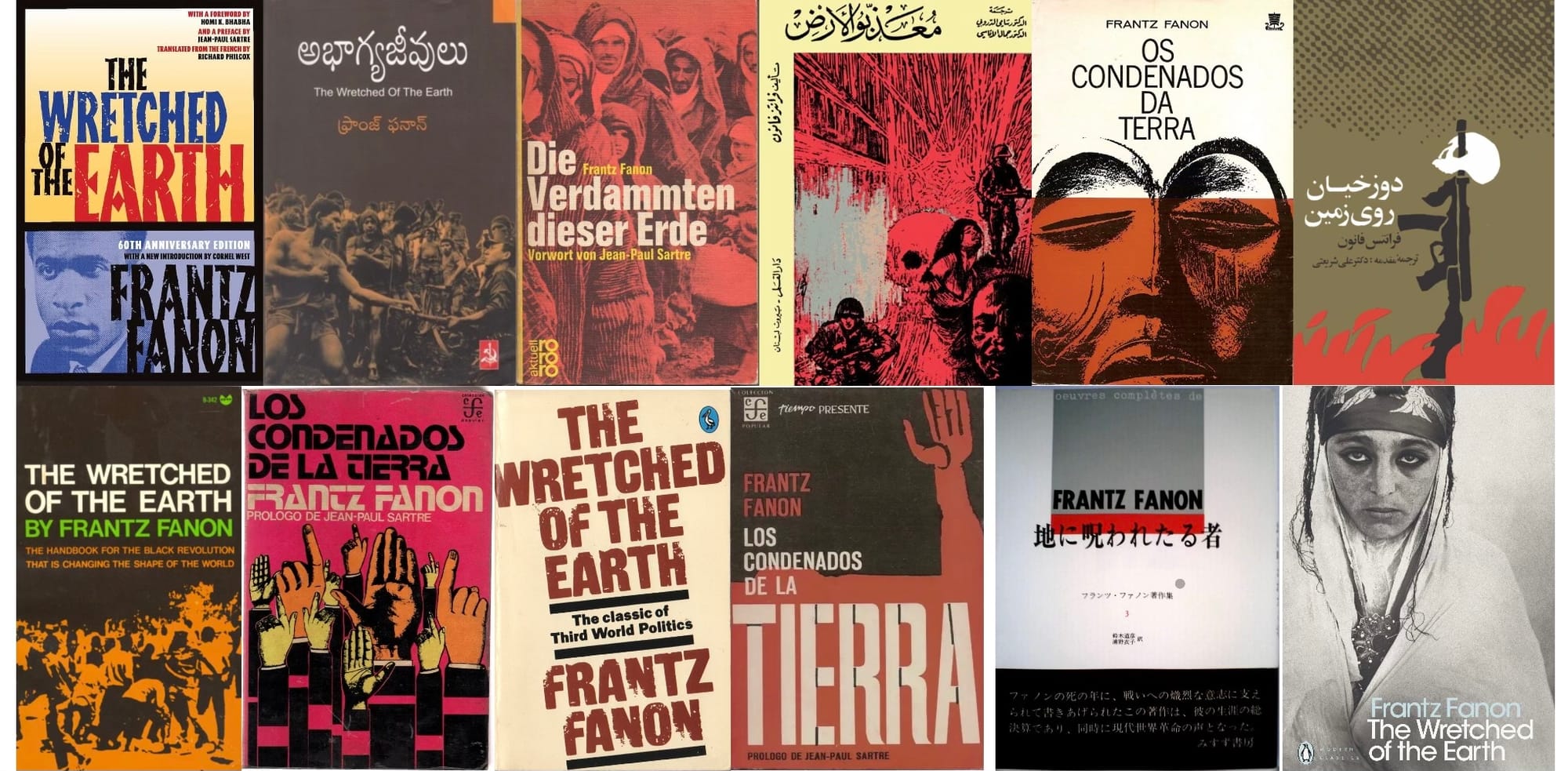

I first read the book while I was in graduate school, but I only began to understand the book’s significance while traveling. In many formerly colonized countries, I could still see the legacy of colonialism in how cities were laid out. I saw the contrast between the dark, narrow lanes of the older historic centers and the broad, tree-lined streets of the new colonial cities. I also saw an image similar to the one below of different translations of The Wretched of the Earth. It had not occurred to me how the book had been translated into various languages. As a white American man, I hadn’t been able to understand the world Fanon described.

In world history courses, we stress the importance of documents such as the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen and the Fourteen Points, but I’ve never seen another world history curriculum that requires students to be familiar with Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth. It’s not even included as an illustrative example in the AP World History Course & Exam Description.

The tendency not to include Fanon in many world history curricula reflects the biases of a mostly White and privileged group of teachers and educators who have influenced what should be taught in world history. Fanon was not writing for us. He was writing for people who had been the victims of European colonialism, imperialism, and racism.

Even after I had read The Wretched of the Earth, it was only after seeing how my students responded to the text that I began to understand better why Fanon matters. Even though I taught in a progressive Quaker school, it was still a privileged New York City independent school. Most of my students came from economically privileged families, but they were the minority of people living in the city. About 25% of my students came from economically challenged families, but they reflected the majority of the city’s population. Those students attended my school because of financial aid, and they usually traveled long distances from the outer boroughs on the subway to attend a school in Manhattan. That same group of students daily saw an elite school with lots of new technology, small class sizes, and a wealth of support services that their neighbors could never attend. Those students watched some of their classmates arrive and leave school in private cars. They listened to their classmates discuss their vacation homes and the distant locations they traveled to over school breaks. They understood the dichotomy that Fanon described.

I remember one student who had been born in Brazil and now lived in a small apartment in Queens, saying how Fanon described his daily experience. After we discussed an excerpt from The Wretched of the Earth in class, he asked for a copy of the book. I happily “loaned” him my copy. I never saw the book again, but I knew he read it. Ten years later, I bumped into him, and he told me he still had it. And he thanked me for having students read Fanon.

Those experiences taught me why all students should read Fanon when teaching world history. For many students today, it’s difficult for them to understand why some colonized people turned to violent resistance. Gandhi’s peaceful resistance looks successful in the history books. Students who have grown up with privilege can struggle to understand why Algerians, Kenyans, Vietnamese, and many other colonized people abandoned peaceful forms of resistance and turned to violence. By using a few excerpts from Fanon, we can help students begin to understand the effects of colonial violence on the process of decolonization and to start becoming aware of their privilege.

Preparing to Teach Frantz Fanon

This content is for Paid Members

Unlock full access to Liberating Narratives and see the entire library of members-only content.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in