Europeans Didn’t Discover the World

It’s time to stop calling it an “Age of Discovery” or an “Age of Exploration”

Table of Contents

📍 My Medium Friends can read this essay on Medium.

📍 Love the community on Substack? Read this essay there.

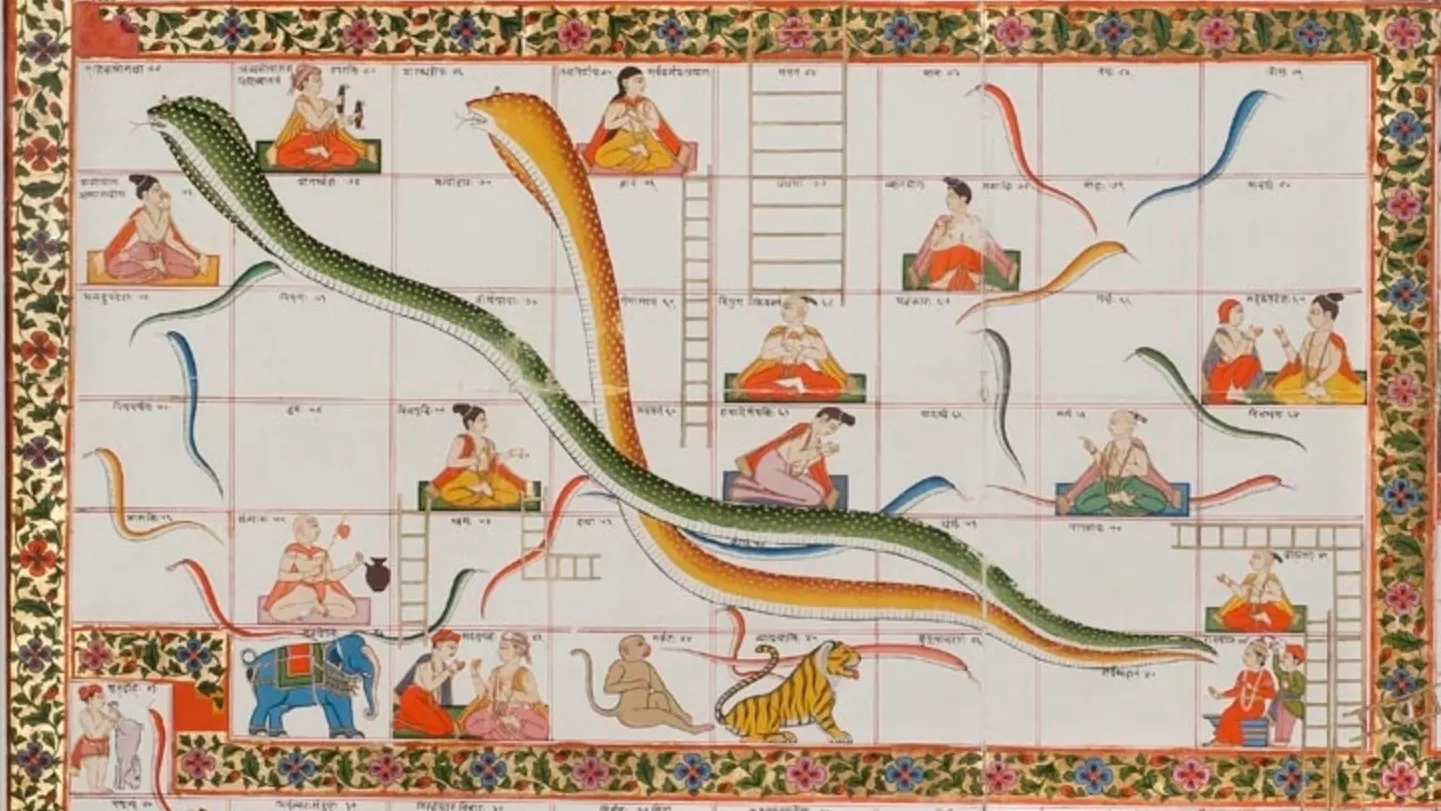

Last Monday was Indigenous Peoples’ Day, although the sign at my local library still said “Columbus Day.” I was disappointed, but I wasn’t shocked that a library in South Carolina still refers to the second Monday in October as Columbus Day rather than Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Unfortunately, the myth of Columbus and the “Age of Discovery” is powerful in the United States. Even in many present-day world history textbooks and websites, writers and editors still describe the European voyages in the 1400s and 1500s as an “Age of Discovery” or an “Age of European Exploration.” These phrases aren’t neutral; they reflect a Eurocentric bias in our understanding of world history.

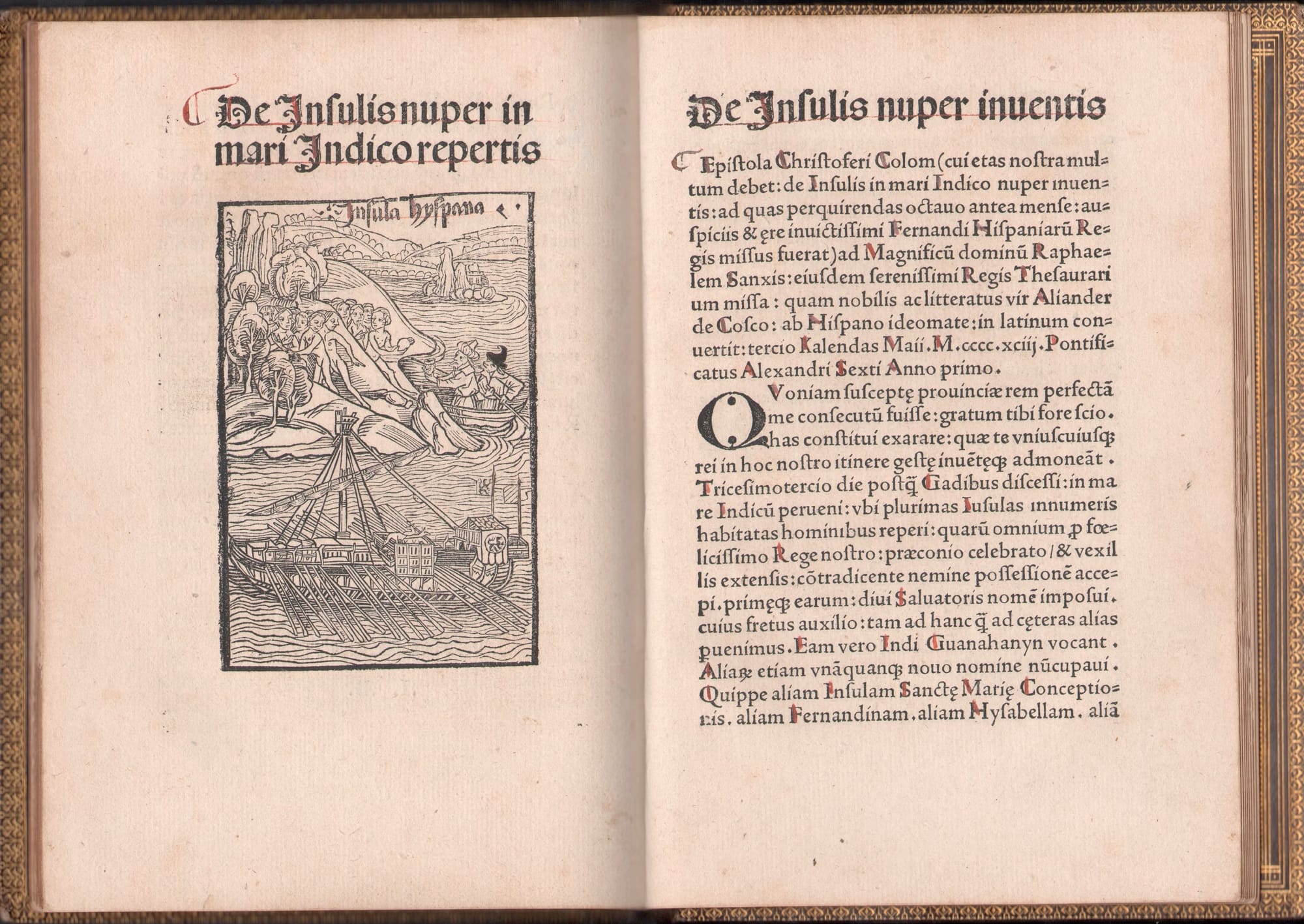

To help students think about the problem with using “discovery” or “exploration” to talk about Columbus or other European navigators, we can start with Columbus’ 1493 letter to the Spanish court reporting on his voyage. He wrote this letter on the journey back from the Americas to describe what had happened. The letter was reprinted and distributed across Europe in the following years. When students read this letter, I ask them to examine closely the first two sentences:

I have determined to write you this letter to inform you of everything that has been done and discovered in this voyage of mine. On the thirty-third day after leaving Cadiz I came into the Indian Sea, where I discovered many islands inhabited by numerous people.

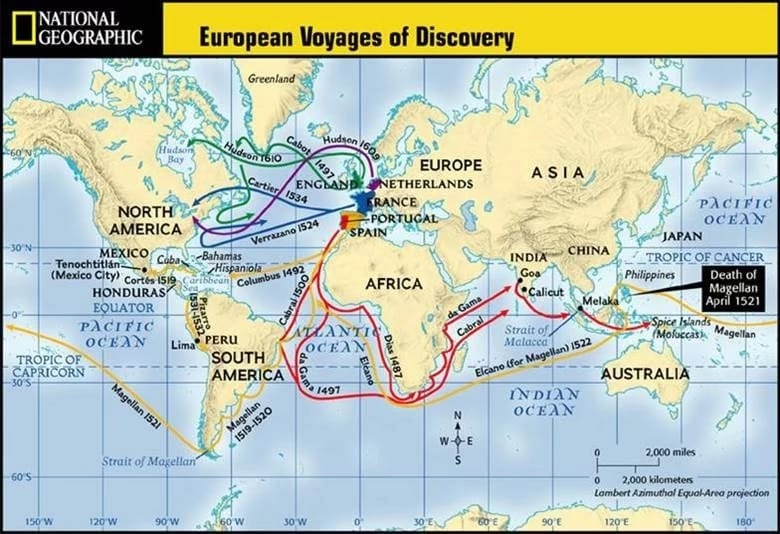

Columbus himself twice used the word “discovered.” Some translators use “found” instead, which seems minor considering the rest of the quote. The “many islands” that Columbus “discovered” were “inhabited by numerous people.” How do we discover a place where many people already live? Columbus’ own words reveal his Eurocentrism. Even though he acknowledged that many people lived in the Caribbean Islands, their existence didn’t matter. He had “discovered” the islands. When we repeat Columbus’ claim that he “discovered” the Americas or that other Europeans, such as Vasco da Gama or Ferdinand Magellan “explored,” we are ignoring the millions of Indigenous Americans, Africans, and Asians who lived in these places before Europeans showed up.

In Airplane Mode: An Irreverent History of Travel, Shahnaz Habib, an Indian writer who grew up in Kerala, India (one of the places that Vasco da Gama is said to have “discovered” a route to), writes about her reaction to the notion that Europeans discovered places outside Europe:

People of color often use air quotes when we talk of explorers who “discovered” the Americas or India or various Pacific islands. Alas, it is hard to translate air quotes to text. Even when retranslated back as quote marks (see “discovered”), something is missing. My fingers often itch to include the eye-rolling and smirking that we use to accompany air quotes. I propose instead a new word: pseudiscovery. The silent p, I hope, will convey the silence of our air quotes, the people and places who were rendered invisible when Europeans pseudiscovered them.

Habib captures perfectly how people from the rest of the world feel about these persistent phrases. The “Age of Discovery” and the “Age of Exploration” are relics of a Eurocentric narrative of world history. Africans, Asians, and Indigenous peoples only mattered once Europeans discovered how to travel across the world’s oceans. When we use these phrases, we alienate the many students in our classes whose families come from the places Columbus, da Gama, and Magellan “discovered.” The next time we teach about these European navigators and their important voyages, let’s not call them discoveries or explorations. They were part of the Age of Maritime Navigation and Colonization.

Thanks for reading 🙏

Liberating Narratives is written by Bram Hubbell. If you’ve valued reading this post, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your financial contribution supports independent, advertising-free materials for teachers. Thank you, friends.

Feel free to forward this message to a friend or colleague and let them know where they can subscribe. (Hint: it's here.)

If you have any comments or suggestions, please share them with me or post them below. I can also be reached on Bluesky, Threads, Facebook, Instagram, Mastodon, and email.

Liberating Narratives Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.