“The Great Mass of Snow and Hail”: Teaching the Little Ice Age, c.1300 - c.1800

Discussion of teaching the Little Ice Age in world history

In 2005, Felipe Fernández-Armesto published The World: A History, a unique world history textbook. He avoided the typical periodization found in most textbooks. For example, he didn’t divide the eighteenth century in 1750. Instead, he included multiple chapters that span the eighteenth century from 1700 to 1800. Many world history teachers and professors were puzzled by Fernández-Armesto’s periodization choices, but one of his unique choices resonated with many teachers. His chapter on “The Revenge of Nature: Plague, Cold, and the Limits of Disaster in the Fourteenth Century” combined the demise of the Mongol Empire, the Black Death, the Little Ice Age, and historical exceptions in Afroeurasia and the Pacific. I remember talking with many excited teaching colleagues. They appreciated how he brought together seemingly separate events in a compelling narrative. Anyone reading this newsletter will also most likely know that Fernández-Armesto’s textbook never caught on or became popular in high school or college world history courses.

As I flip through that chapter today, I realize why I was so excited about it. Fernández-Armesto compellingly told a story that blended political and “natural” events while including exceptional cases. He didn’t oversimplify the Little Ice Age into a catastrophe that ended a civilization. At the time, Jared Diamond had just published Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. Other books also focused on how dramatic events plunged society into a “dark age” or “saved civilization.” Fernández-Armesto’s textbook also came out just two years after The Day After Tomorrow, one of the first blockbuster movies about climate change. Even today, few textbooks cover the Little Ice Age in much detail. There typically is only a brief mention of the Little Ice Age when discussing the Black Death or the political upheavals of the seventeenth century.

Despite the lack of coverage in world history textbooks, the Little Ice Age is an important topic to cover in world history. Too often, world history courses overly emphasize political shifts, trade, and cultural exchange. We need to help students recognize how humanity exists in relationship to the natural world. Over the next month, I will focus on the Little Ice Age. This first post will highlight what the Little Ice Age was, why we want to teach it, and how we can approach the topic. Each week, I will discuss some standard world history topics that naturally lend themselves to teaching the Little Ice Age.

Defining the Little Ice Age

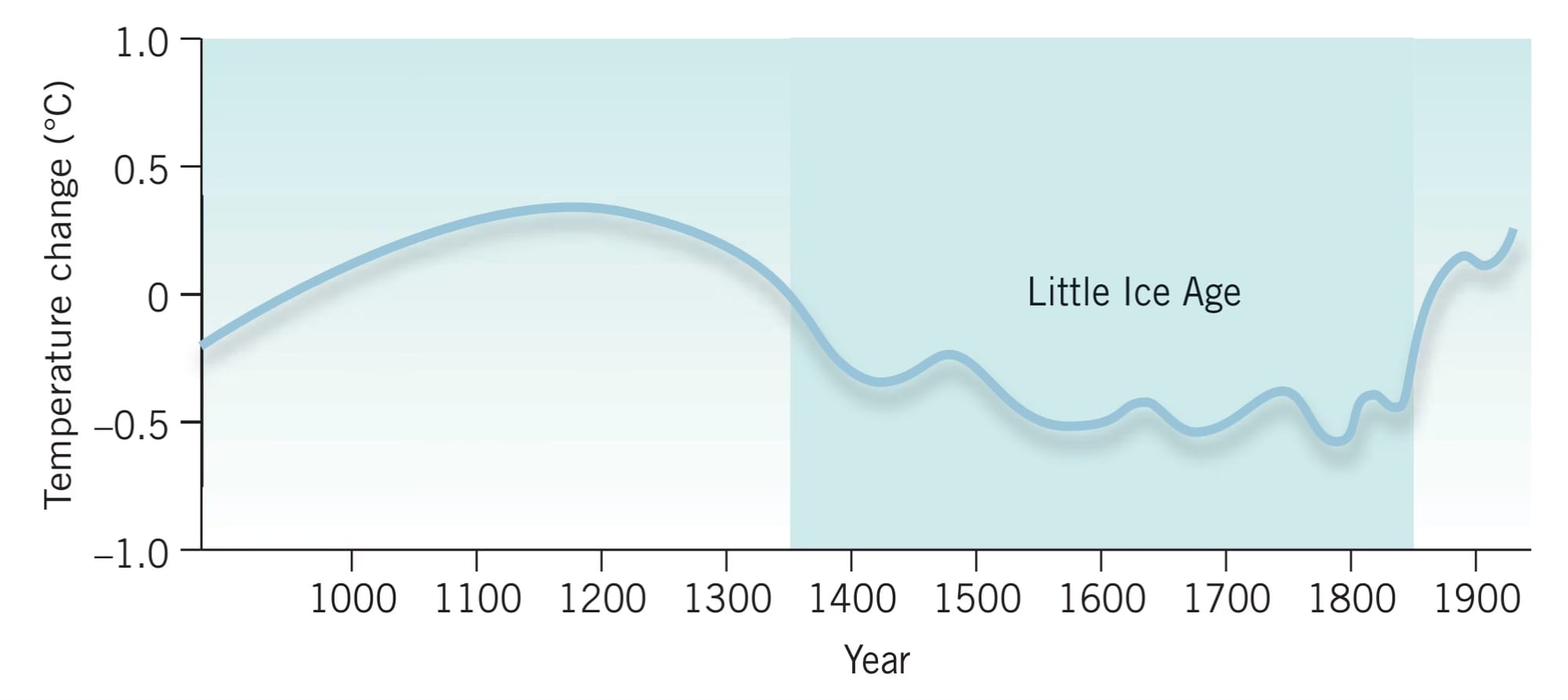

At the most basic level, the Little Ice Age was a period of slightly cooler temperatures from 1300 to 1800. Although the Little Ice Age affected the whole globe, the cooler temperatures had a notable effect on the North Atlantic region. The cooler temperatures contributed to several other effects, such as variations in precipitation, fluctuations in the strength of the Indian Ocean monsoon, increased storminess, glacial expansion, and sea-level changes. Some regions experienced droughts, while others experienced flooding. Because of the variations in precipitation, farmers often struggled to grow as much, which in turn contributed to famines.

Historical climatologists do not know the exact cause of the Little Ice Age. Recent research has suggested that the four volcanic eruptions, beginning with the Samalas volcano in Indonesia in 1257, were the initial cause of the Little Ice Age. The increase of volcanic ash in the atmosphere contributed to cooler temperatures. Subsequent volcanic eruptions continued to affect the climate. There were also periods of decreased sunspot activity, such as in the seventeenth century.

I typically avoided discussing the science of the Little Ice Age since it can be confusing. In a history course, students don’t need to know the scientific intricacies; they simply need to know that it got colder! I used the graph of the temperature change and asked students to focus more on how cooler temperatures would have affected humans. The Crash Course episode on the Little Ice Age is also a helpful introduction since it focuses more on how the Little Ice Age affected humanity.