Rethinking Industrialization and the Nineteenth-Century Global Economy

Discussion of the nineteenth-century global economy, industrialization, and the production revolution

Table of Contents

When I first imagined writing this series on the Production Revolution, I simply wanted to find a better way to integrate the whole world into how we teach the Industrial Revolution. Too often, we teach about why some places industrialized and others did not. As teachers, we are increasingly aware of the value of an asset-based approach to education. If we want to highlight students’ strengths, why are we teaching them to focus on finding why some states failed to industrialize?

The synagogue in Jonava. It’s been rebuilt over the years but seemed a sizable structure for what my family called a village.

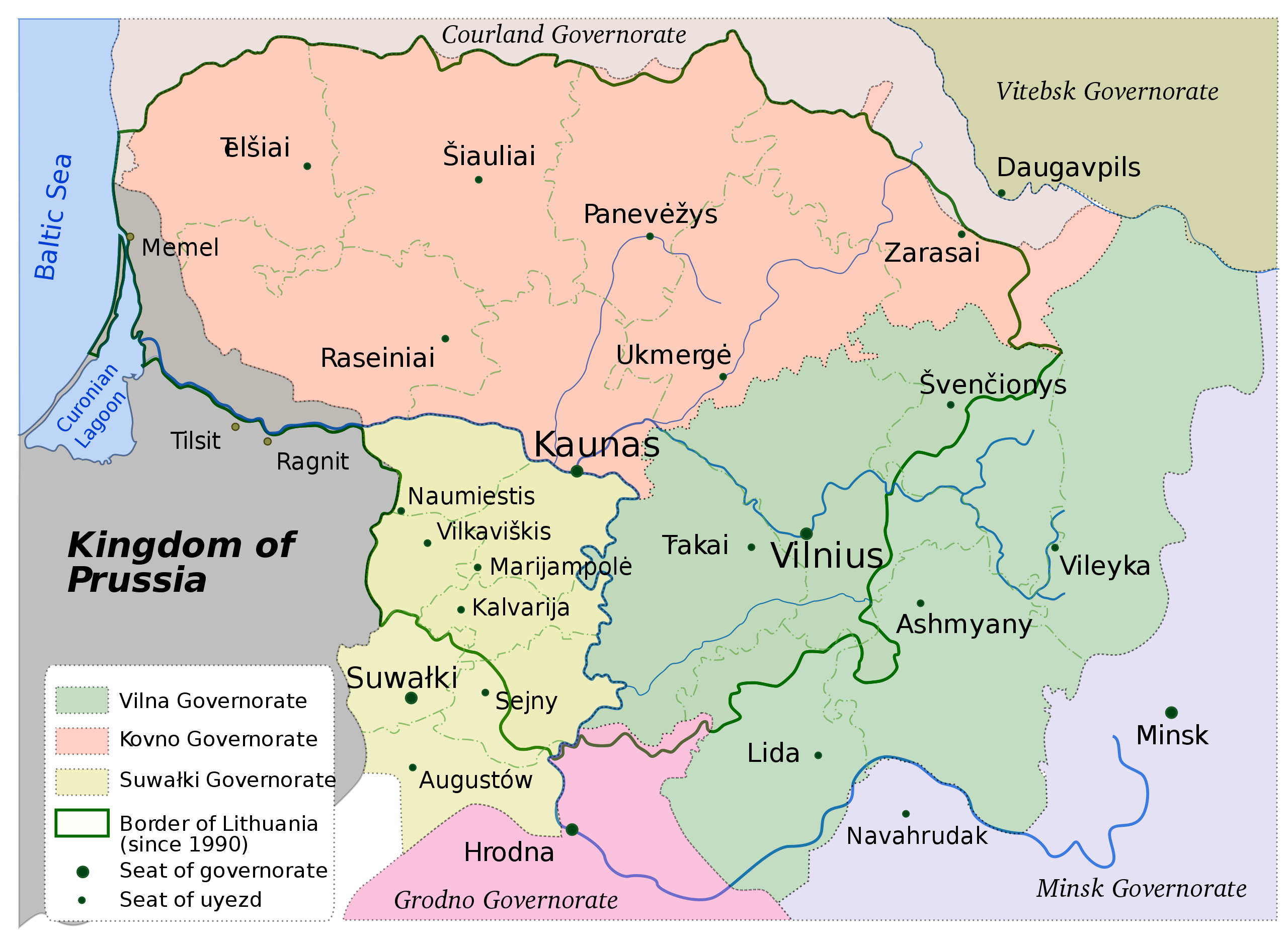

I started questioning how we taught industrialization when researching my family’s history. My mother’s maternal grandmother came from present-day Lithuania, part of the Russian Empire at the end of the nineteenth century. She and her family were Jewish and lived around present-day Kaunas, but her children called it “Kovna.” As I searched the records, I learned most lived in Jonava and a nearby small village. My great-grandmother’s family migrated to Worcester, Massachusetts, between 1897 and 1903. In the 1980s, my family still told stories about the shift from “the village” to “the city.” They didn’t think of where their ancestors lived as having been affected by the Industrial Revolution.

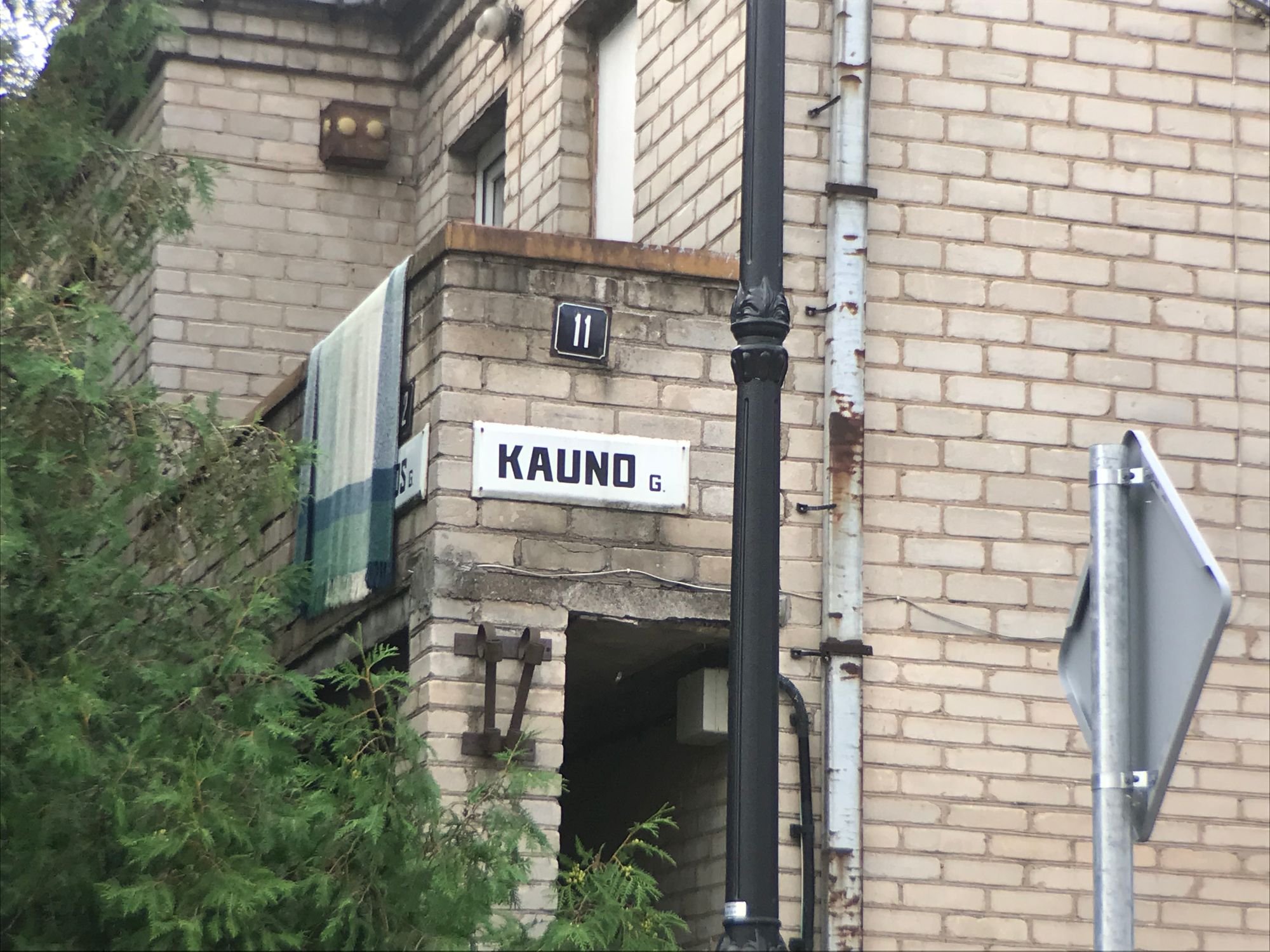

I traveled to Lithuania in 2018 to see where my family came from. Visiting the place “Bubbe,” my great-grandmother, was born helped connect me to my ancestors. She passed away when I was 17, so I have memories of her. I was close to all six of her children, so they helped keep Bubbe’s memory alive. I was surprised by what I found. The village is now underwater because of a mid-twentieth-century dam. Kaunas, the present name for Kovna, is definitely a city and was in 1900. I loved walking down its main cobblestone road. Jonava was not a big city, but it was something between a large town and a small city. Many Jewish families made furniture that was sold in the surrounding region. The main road linked Jonava to Kovna, and trade flowed in both directions. As I looked at the old photographs, I saw all the signs of a place in transition. I saw the signs of industrialization. My family remembered what Lithuania lacked; I saw Lithuania’s strengths. I saw an area experiencing a production revolution.

Top Left: Jonava around 1900. Top middle: The Road to Kaunas in Jonava. It was the same road to Kovna in 1900. Top right: Kaunas. Bottom left: Kaunas' synagogue. Botton right: Main square of Kaunas.

Reflecting on what I saw in Lithuania helped me rethink how we teach the Industrial Revolution. We talk about places that industrialized and places that didn’t industrialize. We don’t use the word “failure” to describe those places that didn’t industrialize, but it’s lurking in the subtext of those conversations about why Egypt didn’t industrialize. Egypt is a bad student; Japan is a good student. We find the reasons for Japan’s success and focus on Egypt’s failure. As I discussed in the post on Egypt, maybe we should focus less on why Egypt didn’t become the next Manchester and more on what Muhammad Ali and the Egyptians achieved. Let’s talk more about Egypt’s nineteenth-century strengths.

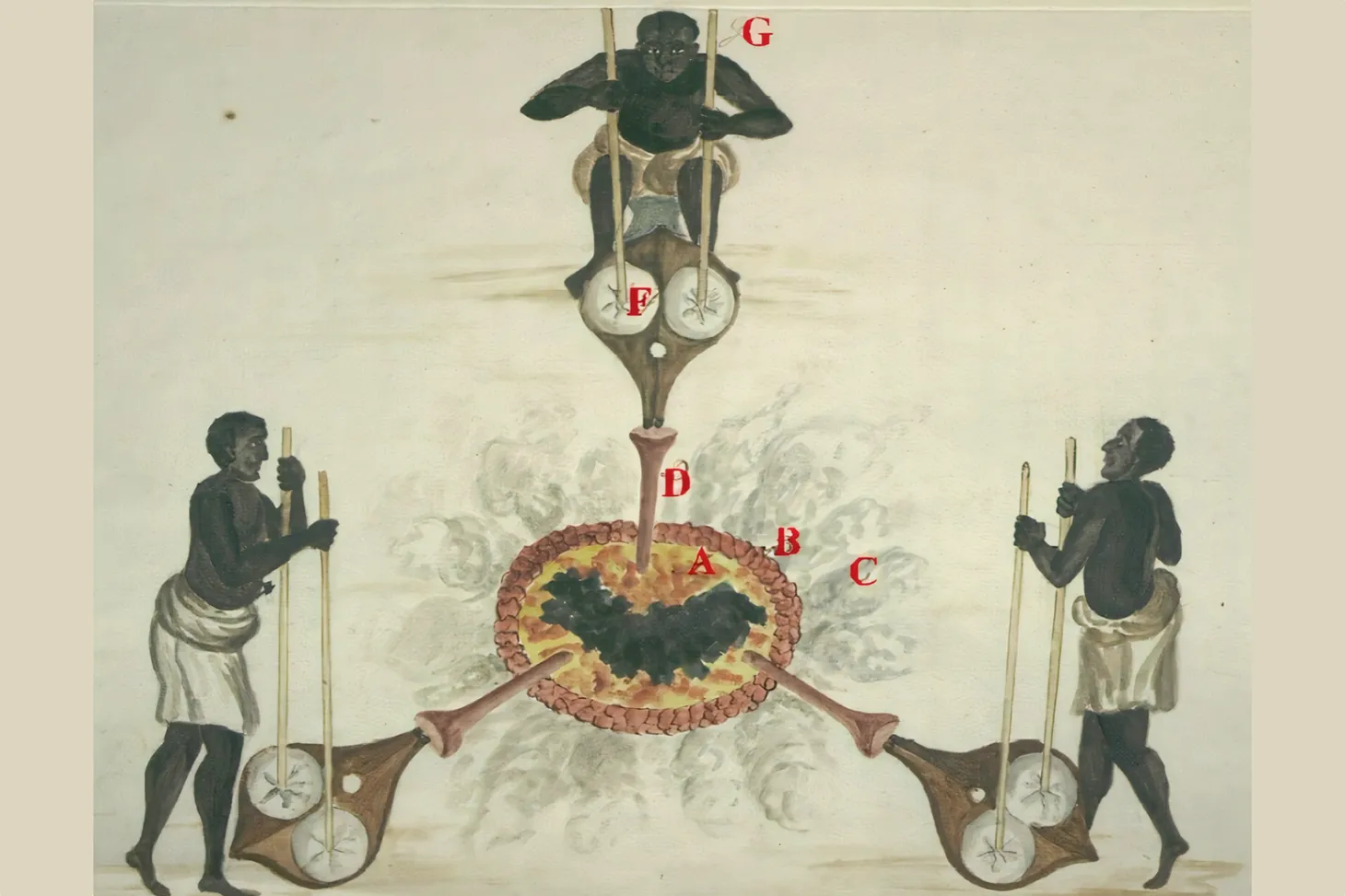

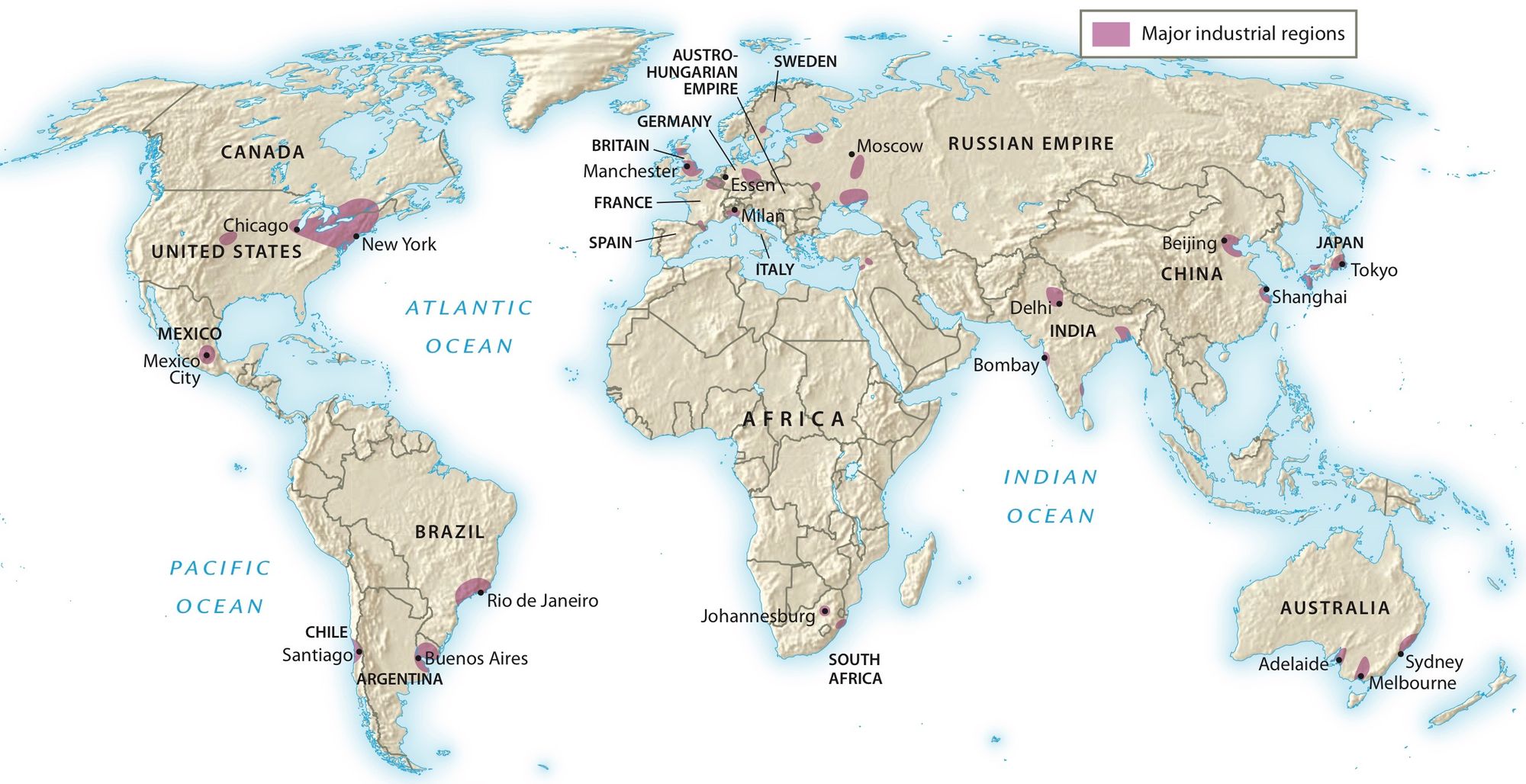

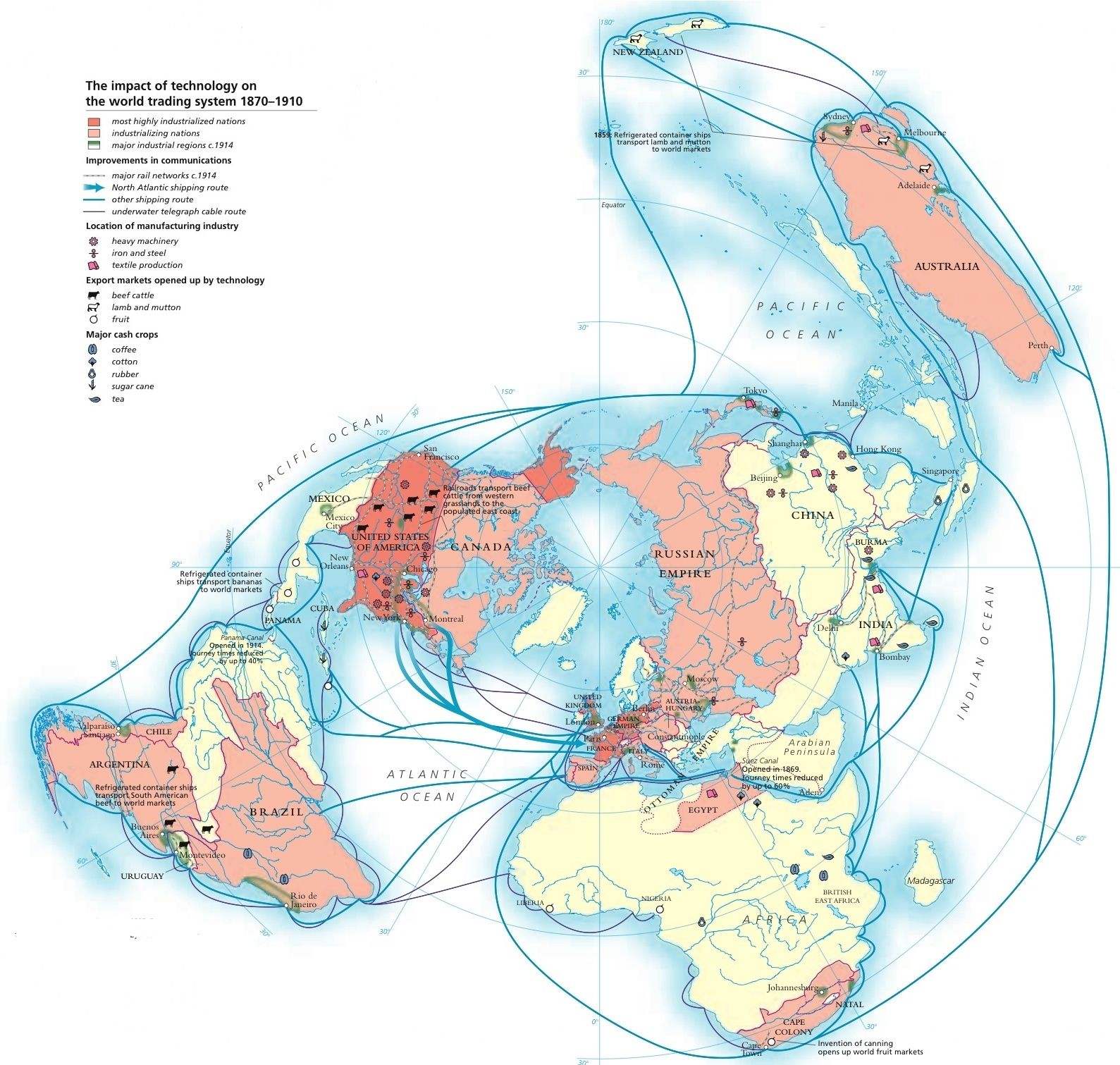

It wasn’t just Egyptians experiencing a production revolution in the nineteenth century. There were Cuban colonists mechanizing sugar plantations. Bengali jute farmers grew the essential fiber for transporting commodities worldwide. West African peanut and palm oil farmers harvested the materials for soap and industrial lubricants. And Southeast Asian rice farmers fed much of Asia. Next time we teach the Industrial Revolution, let’s not focus only on the industrializing regions. Let’s highlight how people worldwide actively contributed to a new global economy.

Left: The world in 1900 - showing only the successful students where industry was emerging. Right: The global economy in 1900. Source: Fernandez-Armesto's The World: A History.

Liberating Narratives is written by Bram Hubbell. If you’ve valued reading this post, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your financial contribution supports independent, advertising-free materials for teachers. Thank you, friends.

If you would like, please forward this message to a friend or colleague and let them know where they can subscribe. (Hint: it's here.)

If you have any comments or suggestions, please share them with me or post them below. I can also be reached on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Threads, Mastodon, Bluesky, and email.

Liberating Narratives Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.