Healing the Sick Man of Europe

Table of Contents

If the Ottoman Empire in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was going through a period of transformation, rather than beginning a 400-year decline, it would seem that the Empire, which collapsed in 1922, had to be declining in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. While it’s true that the Empire lost substantial territory, too much focus on the territorial loss and the collapse of the empire can blind us to the important positive developments taking place in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The Supposedly Sick Man of Europe

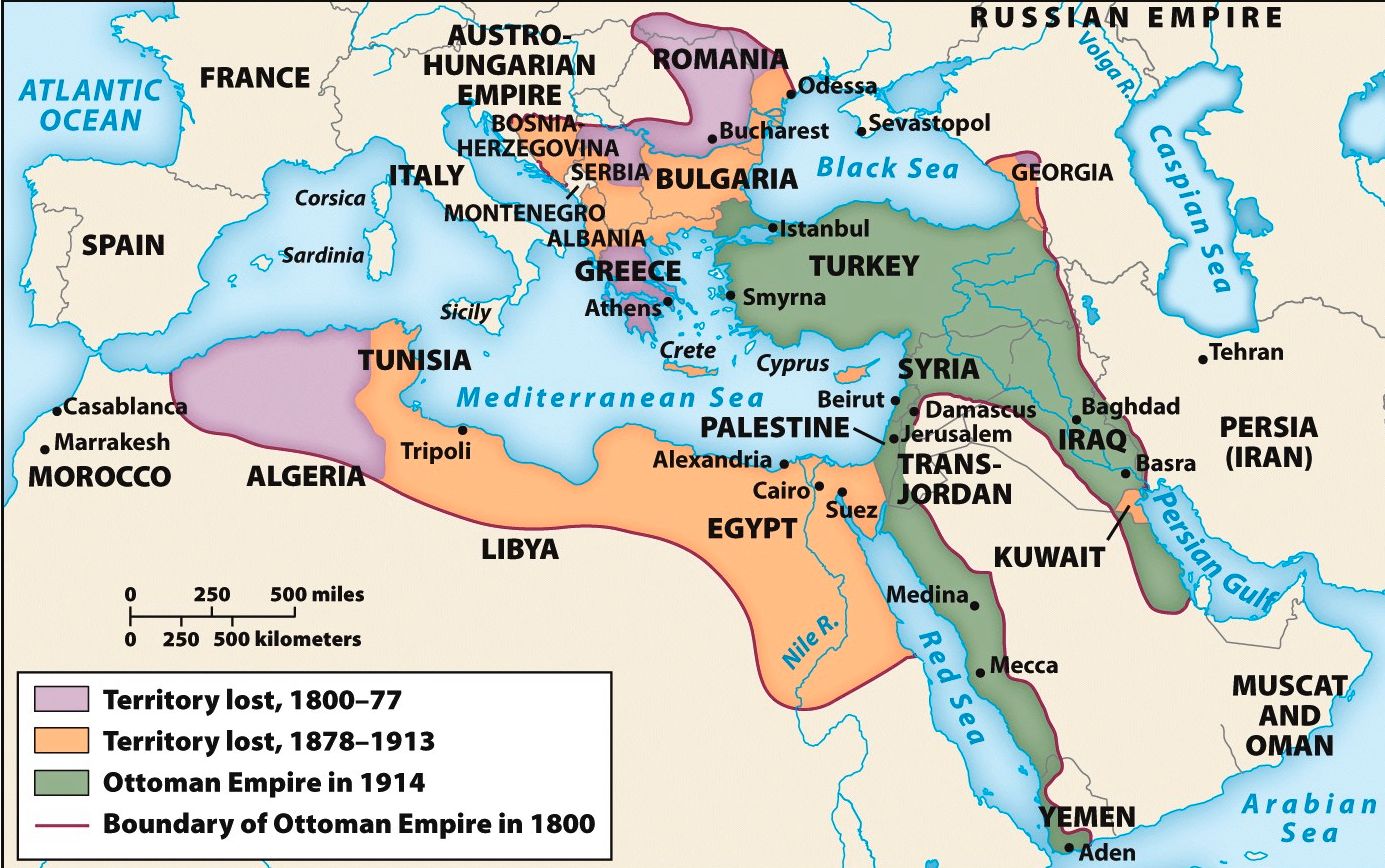

If we look at the map of the Ottoman Empire during the nineteenth century, talking about decline seems logical. We can easily see that the Ottomans lost control of more than half their territory. On the eve of the First World War I, the Ottoman Empire had contracted to the area around Istanbul, Anatolia, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. At some point during the middle of the nineteenth century, European diplomats, believing that the Ottoman Empire was near its end, began calling the Ottoman Empire the “Sick Man of Europe.”

In thinking about this epithet, there are two important points. The first is that European diplomats using this phrase saw the Ottoman Empire as part of Europe. From our present-day perspective, we tend to think about the Ottoman Empire as being in the Middle East. World history courses treat the Ottomans as an Islamic or Middle Eastern empire. In courses about the Middle East, the Ottoman Empire tends to be the most important state. While the Ottomans were undisputedly a Middle Eastern state, since the fifteenth century, the Ottomans were also a European state. Even if European diplomats believed that the Ottoman Empire was dying, they also believed it was a European state that was dying.

The second point to consider is how this popular epithet influences our understanding of the history of the Ottoman Empire in its final two centuries. It’s easy for students to hear this epithet and become focused on why the Ottoman Empire collapsed and what came after it. As a teacher, I know that I am often asking my students to explain why particular empires collapse. The issue with this teleological focus is that it can blind us to the significance of Ottoman reform and modernization during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In his A Brief History of the Late Ottoman Empire, M. Şükrü Hanioğlu argues:

the attempt to frame late Ottoman history in a narrative of imperial collapse to the relentless drumbeat of the march of progress — usually associated with Westernization, nationalism, and secularization — prevents a clear understanding of the developments in question.

In the rest of this post, I want to shift the focus away from Ottoman decline and toward the ways in which the Ottoman state evolved and adapted. These transformations allowed it not only to survive for so long but also to assert greater control over the territory that it continued to rule.

The Eighteenth Century Evolutionary Ottoman State

Having acknowledged that the Ottoman Empire contracted significantly during the nineteenth century, the question becomes what was still dynamic about the Empire. If we look at the state itself, we quickly see that while the Ottomans ruled over far fewer people, the state’s ability to rule over these people had increased substantially. In her Empire of Difference: The Ottomans in Comparative Perspective, Karen Barkey argues about the important changes of the eighteenth century:

The seeds of transition from empire to a different political formation were sown in the eighteenth century. The central and local structures of the empire began to take a different shape, connecting nodes and further decreasing peripheral segmentation.

After centuries of adaptive and flexible policies that had maintained the Ottoman Empire as a relatively decentralized empire, the rulers of the state began the process of transforming the Empire into a more centralized nation-state. Barkey focuses on a few key eighteenth-century developments in the Ottoman Empire: the emergence of new movements of opposition to the state that began framing “a new state-society compact,” the commercialization of the Ottoman economy, and “the widespread growth of tax farming as a significant form of revenue collection.” These transformations, according to Barkey, highlight the ways in which the Ottoman Empire continued to evolve and adapt. She also emphasizes that these adaptations should be seen as “a sign of flexibility and pragmatism, not a sign of decline.” It’s also worth noting that the methods of reform adopted by the Ottomans sometimes reflected and sometimes diverged from European methods of political and economic reform. These reflections and divergences remind us that the European model of reform was not the only model; there were multiple ways that states modernized during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The Nineteenth Century Evolutionary Ottoman State

The Ottomans’ transformation of the state continued into the nineteenth century. Beginning in 1839, Ottoman rulers implemented the Tanzimat, a series of reforms that reshaped the nature of the Ottoman state. The Tanzimat included laws guaranteeing property rights, prohibiting bribery, replacing tax farming with a more consistent system of taxation, abolishing differential treatment of Muslims and non-Muslims and different ethnic groups, encouraging a more secular vision of the Empire, and establishing equitable universal conscription of males into the military. The Constitution of 1876 is often seen as the culmination of these reforms since it formalized and codified nearly forty years of legal changes. These changes not only highlight the ways in which the Ottomans were adapting elements of European states but also indicate the increasing strength and centralization of the Ottoman state. Hanioğlu argues that the three individuals (Mustafa Reşid Pasha, Mehmed Emin Âlî Pasha, and Keçecizâde Mehmed Fu’ad Pasha.) responsible for these reforms also mark a shifting balance of power within the imperial rule. Instead of competition between different factions within the state, “the bureaucratic cadres of the Sublime Porte [the name for the entrance gate to buildings housing the Ottoman bureaucracy ] oversaw the entire administration of the state, ruling the empire until 1871 with only trivial interference from the imperial palace or the ulema.” The Tanzimat also marked a reassertion of Istanbul’s power over the provinces of the Ottoman Empire. According to Hanioğlu, the leaders of the Tanzimat implemented “new regulations that would make local administration uniform throughout the empire.” After forty years of the Tanzimat, there was a major shift in the governance of the Ottoman Empire in 1878. Sultan Abdul Hamid II seized control of the government and suspended the two-year-old Constitution. While Abdul Hamid is known for suspending the Constitution of 1876 and promoting a more Islamic vision of the Empire, he also continued the centralization of the state and expanded the central government’s influence over the provinces. One way in which he combined these two trends is in his call to build the Hijaz railway. Ostensibly promoted as a way to link the major cities of the Empire to Mecca to facilitate the hajj, it was also a way to more easily move soldiers and officials across the Arab provinces. Abdul Hamid also reorganized and expanded the Ottoman bureaucracy in a way that made it increasingly dependent on him personally. Hanioğlu argues:

Abdülhamid II in fact envisioned efficient administration of the empire by a modern bureaucracy headed by a cadre of technocrats. Accordingly, bureaucratic reform picked up perceptible speed during his reign. At the sultan’s behest, a host of new bureaucratic schools were established, including the Royal Academy of Administration, which became a college.

Over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Ottoman Empire continued its long-standing practice of evolving and adapting its systems and practices for ruling over its vast territory. Whereas the early history of the Empire was characterized more by flexibility and localized practices, the last two centuries of the Empire increasingly became characterized by centralization and standardization.

The Effects of Centralization

This increased centralization, not surprisingly, was often resisted by people around the Empire. Hanioğlu shows how a wide range of people pushed back against the Ottoman imperial officials. Whether it was Christians in the Balkans, bedouins among the Arab nomadic populations, or Arabs in Mount Lebanon, there was an empire-wide trend of resistance by formerly loosely-ruled peoples to the new, more invasive practices of the Ottoman government. In some regions of the empire, this resistance was successful. During the late nineteenth century, Christians in the Balkans successfully led nationalist independence movements in Bulgaria and Serbia.

At the same time, the Ottomans also managed to reassert control over other parts of the Empire. In 1870, the Ottomans sent forces to Yemen and reestablished nominal control over much of the country. Also during the 1870s, the Ottomans reestablished control over Transjordan. They set up Salt as a regional capital, stationed soldiers in the region, and asserted control over the formerly independent Bedouin tribes. The Ottomans even began to encourage the migration of Circassians and Palestinians to the region and linked Transjordan to the rest of the Arab provinces through the Hijaz railway.

What happened in Transjordan and Yemen also happened across much of Anatolia, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. Even as the Ottomans lost control of territory in the Balkans and North Africa, their ability to govern their remaining provinces increased.

The Ottomans as an Imperial Power

Another way to think about the increased power of the Ottoman Empire in the nineteenth century is to consider its ability to project its influence beyond its borders. In an interview on the Ottoman History Podcast, Mostafa Minawi discuss “The Ottoman Scramble for Africa.” Chris Gratien, who interviewed Minawi, expands on his ideas in an article of the same name. As European powers sought to expand their power into Africa, they also viewed the Ottomans as needing to be included in discussions at the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885. According to Gratien, the Ottomans participated in these meetings by:

closely following the legal terms of the conference in order to claim parts of Sub-Saharan Africa as the “hinterland” of their remaining North Africa provinces. Likewise, they tried to hold their European competitors in Africa, such as France and Britain, to these terms in order to stop the contraction of their empire. In this way, they used these new agreements to assert their sovereign position on the world stage.

Gratien also explains how:

Ottoman activities in Africa went beyond formal claims. They sought to establish telegraph lines and other political and cultural connections with the local Sanusi order in order to lay claim to a tangible presence on the ground. Here, Minawi notes the potential dangers of labeling the Ottomans as another colonial power, because their strategies differed markedly from those of some of their European contemporaries. Rather than asserting themselves as the rightful and hegemonic rules of a borderlands region, they represented themselves to their local interlocutors as alternative allies to the otherwise impeding arrival of European colonial rule.

Based on both their participation at the Berlin Conference and actions they took on their own, the characterization of the Ottomans as the “sick man” obscures our ability to see the ways in which the Empire was still a surprisingly strong state able to project its power into Africa right up until the end of the nineteenth century.

Conclusion

Over the course of this post and the previous post on the Ottomans, I have suggested that the tendency to view the Ottoman Empire after the death of Süleyman in 1566 as a long history of decline is problematic. Not only did the Empire last for nearly 450 years more, but in many ways, the political power of the Empire was surprisingly quite strong. The Ottoman government developed multiple strategies over the years to rule over a large amount of territory. At times these strategies mirrored ones adopted by Europeans, but at other times the Ottomans adopted unique strategies. So often the challenge in world history is to escape the Eurocentric assumptions that shape our narratives. If we can use a few detours along the less traveled narrative roads of world history, hopefully, our students will be better able to figure out how to navigate the world of world history on their own rather than continuing to rely on outdated Eurocentric maps.

Liberating Narratives Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.